Unveiling the Unique Ingredients in Northern Pakistan’s Culinary Landscape

Tucked away in the mighty folds of the Karakoram and Himalayan ranges lies a region where cuisine is as awe-inspiring as the landscape itself. From the apricot-laden orchards of Hunza to the snow-covered valleys of Skardu, Northern Pakistan offers a food culture shaped by altitude, ancestry, and absolute authenticity.

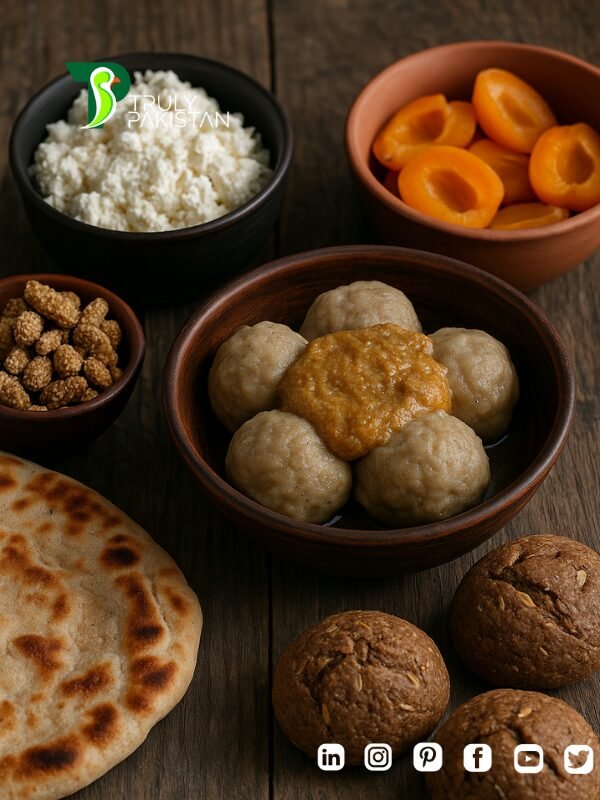

But what truly sets this region apart are the rare, hyper-local ingredients that flourish here, and nowhere else. These unique ingredients in Northern Pakistan are born of glacier-fed irrigation, traditional preservation methods, and a deep-rooted connection between communities and their environment. Whether it’s the nutrient-dense sprouted wheat breads, barley dumplings drizzled with apricot seed oil, or handmade cheese from boiled yogurt, every ingredient carries history, purpose, and place.

This feature explores 10 such treasures—each telling the story of sustainability, survival, and cultural identity in one of the most breathtaking yet challenging terrains on earth.

If you’ve ever wanted to taste what nature, tradition, and resilience create together, you’ll want to start right here.

1. Apricots & Apricot Oil – The Golden Gift of Hunza

In the Hunza Valley—often romanticized as the “Shangri-La” of Pakistan—apricots are more than fruit; they are a way of life. With snow-dusted peaks on one side and terraced orchards on the other, the valley comes alive every spring with the golden bloom of apricot trees, known locally as chuli. These trees are so abundant that almost every household owns at least a few, growing different varieties that ripen at staggered times between May and August.

What makes apricots from Hunza so special is not just their flavor, but their entire lifecycle of use. In summer, they’re eaten fresh, juicy, fragrant, and slightly tart. At peak ripeness, villagers begin the process of sun-drying them on flat rooftops, carefully turning them daily to ensure even dehydration. These dried apricots become a staple winter snack and are often served with green tea or added to porridges and stews.

But perhaps the most valuable byproduct is apricot oil, extracted by cold-pressing the kernels inside the apricot pits. This golden elixir is treasured in every Hunza home. It’s used for:

-

Cooking—thanks to its nutty flavor and high smoke point,

-

Preservation—as a natural coating for dried fruits and cheeses,

-

Medicinal uses—for massaging sore joints, healing cracked skin, and as a general anti-inflammatory remedy.

Modern nutritionists would be quick to highlight its high vitamin E content, along with essential fatty acids and antioxidants that promote skin health and reduce oxidative stress. Locally, it’s even believed to contribute to the unusually long life expectancy of Hunza residents—many of whom live well into their 90s with minimal signs of age-related illness.

Apricots and their derivatives also take center stage in traditional cuisine. The dish Balay, a rich porridge made from wheat flour and apricots, is commonly eaten to fuel the body in winter months, while Propoo combines barley dumplings with a robust apricot seed sauce, giving the dish both flavor and energy. In both meals, the apricot is used in full—the fruit, the seed, and the oil—a testimony to the valley’s philosophy of zero waste and respect for natural resources.

In a world shifting back toward organic, whole-food living, the Hunza apricot stands as a shining example of sustainable, nutrient-dense, locally sourced food—a golden thread woven into the everyday life, culture, and culinary identity of the north.

2. Yak Meat & Yak Milk – The Alpine Superfoods

In the elevated landscapes of Gilgit, Skardu, and the broader Baltistan region, where the altitude is high and winters are unforgiving, the yak stands as one of the most vital animals in both economy and sustenance. These hardy, long-haired beasts—closely related to Tibetan yaks—are well adapted to cold, oxygen-thin environments and play an irreplaceable role in the food systems of the north.

Unlike cattle or buffalo, yaks graze at altitudes of over 3,000 meters, feeding on wild alpine herbs and mountain grasses. This natural, untouched diet imparts a nutritional richness and earthy depth to the meat and dairy products they provide. Their presence in Northern Pakistan isn’t widespread, making their contributions rare and regionally exclusive, found almost entirely in Gilgit-Baltistan and nearby valleys.

Yak meat is lean yet densely packed with protein, iron, and essential amino acids. It is typically slow-cooked in traditional stews, spiced subtly to allow its rich, gamey flavor to shine through. These stews are not just meals—they are sources of energy and internal warmth, consumed after long days of farming, herding, or trekking in the snow.

The yak’s milk, on the other hand, is a true alpine delicacy. Higher in fat and creamier than cow’s milk, it is used to prepare:

-

Thick, flavorful butter, which is sometimes added to tea or porridge,

-

Fresh or aged cheese, made using simple fermentation methods passed down through generations.

These products form the backbone of the local diet during winter months when access to fresh produce is limited, and caloric needs are high. The high fat content helps maintain body warmth, while the unprocessed nature of the milk and cheese supports gut health and immunity.

Beyond sustenance, yak dairy and meat also carry cultural significance. In festivals, village gatherings, and winter ceremonies, dishes made from yak are served as symbols of hospitality, endurance, and mountain resilience. The meat is often preserved by drying or curing, allowing it to last through months when hunting and farming are nearly impossible.

In essence, yak-based foods are more than just ingredients—they’re alpine superfoods, shaped by nature, geography, and necessity. They represent a deeply rooted relationship between humans and their environment, where every part of the animal is respected, and nothing is wasted. For travelers seeking to truly understand the north’s food culture, yak meat and milk are essential, authentic tastes of the terrain.

3. Burus – The Creamy Cottage Cheese of Hunza

In the remote yet self-reliant villages of the Hunza Valley, where towering peaks shelter an age-old lifestyle, Burus emerges as a quiet hero of local cuisine. This humble, hand-crafted cottage cheese is more than a dairy product—it’s a daily staple, a cultural tradition, and a symbol of nourishment rooted in simplicity and sustainability.

What sets Burus apart from mainstream cottage cheese is its distinct preparation method. It is made not from milk, but from boiled yogurt, which is gently heated until it separates and curdles. This method gives Burus its mildly tangy flavor and soft, creamy texture, somewhere between paneer and ricotta. Once formed, it is strained through cloth and pressed, often shaped into small patties or crumbles for immediate use.

Burus is consumed fresh and rarely stored—its short shelf life reflects the valley’s preference for whole, unprocessed, and chemical-free foods. In a region where refrigeration is limited and packaged dairy is uncommon, Burus represents a time-honored approach to preservation and protein intake.

One of its most iconic uses is in Burus Shapik, a dish that layers crispy whole wheat flatbread with generous scoops of Burus, sautéed with local mint, green onions, or seasonal mountain greens. This dish is traditionally cooked on a flat iron skillet and served during family meals or shared in community gatherings. The combination of fresh herbs, tangy cheese, and toasted bread creates a meal that is not only flavorful and satisfying but also nutrient-rich and digestively light.

Burus is also used in:

-

Simple breakfasts paired with flatbread and herbal tea

-

Stuffed into dumplings or eaten with roasted grains

-

Sometimes mixed with apricot oil for added depth

What makes Burus truly special is its connection to Hunza’s broader food philosophy: making the most out of what the land provides, without excess. The dairy used to make it comes from free-grazing cows or goats, and the process requires no industrial equipment—just firewood, time, and skill passed down through generations.

In a world where processed cheese dominates, Burus reminds us of a more authentic, intentional form of eating. It is food crafted by hand, eaten with reverence, and deeply intertwined with the health and heritage of the people of Hunza.

4. Barley & Barley Flour – The Highland Staple Grain

In the elevated farmlands of Hunza and Baltistan, where the terrain is rugged and the growing season short, barley has earned its place as the most resilient and revered grain. It thrives in the harsh, high-altitude environment where crops like rice or maize struggle to survive. With its deep roots and frost-resistant nature, barley is not just a crop—it’s a cornerstone of survival in Northern Pakistan.

For centuries, barley has been cultivated in terraced fields carved into the mountainside, watered by glacier-fed channels, and tended with traditional hand tools. Once harvested, the grain is dried and ground into flour, which is used in an impressive variety of local dishes. From everyday flatbreads to ceremonial foods, barley is ever-present on the northern table.

One of the most distinctive uses is in Propoo, a Balti specialty made from barley flour dumplings, topped with a savory apricot seed and oil sauce. These dumplings are firm, earthy, and filling—designed to sustain energy for long hours of physical labor, trekking, or herding livestock.

Barley is also:

-

Mixed with local herbs to form porridge or gruel

-

Used in stuffed breads and dumplings

-

Toasted and brewed into nutrient-rich drinks

Rich in fiber, magnesium, and B vitamins, barley supports heart health and digestive wellness, which might explain the long life expectancy and physical stamina of locals in the region.

More than just a staple, barley represents ingenuity, sustainability, and food security. Its presence in northern kitchens is a quiet testament to the power of indigenous crops to withstand climate extremes and nourish communities with integrity.

5. Dried Mulberries – Nature’s Sweet Snack

In the crisp mountain air of Gilgit-Baltistan, where wild fruit trees dot the landscape, mulberries hold a special place in both tradition and taste. When in season, these juicy fruits are picked fresh—white or black depending on the variety—and enjoyed in their ripe, succulent form. But their real magic begins after harvest, when they are carefully sun-dried on rooftops or wooden trays, transforming into a chewy, golden super-snack.

Unlike commercially preserved fruits, dried mulberries in the north are completely natural—no added sugars, no artificial drying. This low-tech, high-skill method of preservation captures the fruit’s natural sweetness while concentrating its nutritional value. The result is a snack that is not only delicious but also packed with antioxidants, vitamin C, iron, potassium, and natural energy.

Highly valued by:

-

Trekkers and nomads who carry them as portable fuel

-

Farmers who eat them during early morning fieldwork

-

Children who enjoy them as guilt-free candy

Mulberries are also sprinkled over breakfast porridges, blended into nut-and-seed mixes, or even infused into local breads and desserts.

Beyond their dietary value, dried mulberries reflect a philosophy of minimal waste and seasonal foresight. In a region where winters can isolate entire communities, food that stores well without refrigeration is not just smart—it’s essential. These berries are a perfect example of how traditional food preservation meets modern nutrition.

Their unique tangy-sweet flavor and chewy texture make them irreplaceable in the local diet—a snack born of the sun, mountains, and centuries of wisdom.

6. Mamtu – The Silk Road Dumpling

In the highland kitchens of Gilgit, Hunza, and Skardu, one dish stands out as a living legacy of the Silk Road: Mamtu. These tender, meat-filled dumplings are a culinary bridge between Central Asia and Northern Pakistan, passed down through generations of travelers, traders, and locals who adapted the dish to fit their mountainous lifestyle and local palate.

Believed to have originated from Uyghur, Kyrgyz, or Tibetan cuisine, Mamtu found a second home in Gilgit-Baltistan, where its preparation reflects a fusion of ancient traditions and local tastes. The dumplings are made from thin dough wrappers stuffed with a well-seasoned filling of minced meat (typically beef or mutton), finely chopped onions, garlic, and a dash of native spices like cumin and black pepper.

The dumplings are arranged in layers inside traditional steamers—usually multi-tiered aluminum pots—and gently steamed until they are soft and aromatic. Once ready, they are served with a variety of condiments, including:

-

Garlic yogurt for creaminess

-

Vinegar-chili sauce for tang and heat

-

Locally made pickles for a fermented kick

Though they resemble the more widely known momos of Nepal or mantou from China, Mamtu in Northern Pakistan has its own identity—less spicy, more savory, and deeply rooted in mountain hospitality. It’s a dish often reserved for guests, gatherings, or celebratory meals, showcasing both effort and care in its delicate folding and slow steaming process.

More than just a comfort food, Mamtu carries the weight of cross-cultural heritage. It reflects the centuries of movement through the Karakoram Corridor, where people, ideas, and recipes intermingled. Each Mamtu served today is a tribute to that legacy—a bite-sized piece of history seasoned with community, geography, and resilience.

Whether savored in a roadside eatery in Gilgit or handmade in a stone house in Karimabad, Mamtu is more than just delicious—it’s meaningful.

7. Balay – A Warming Wheat & Apricot Dish

When winter cloaks the mountains of Northern Pakistan in snow and silence, locals turn to Balay, a dish that epitomizes warmth, comfort, and survival. This traditional porridge-like meal is made using wheat flour, fresh or dried apricots, and generous amounts of butter, often sourced from yaks or made from apricot seeds. It is the kind of food that fills not just the stomach, but the soul.

The process begins with slow-cooking wheat flour in water, stirring it into a thick, smooth base over a low flame. Fresh apricots, when in season, are chopped and added directly. During winter, dried apricots—preserved from Hunza’s orchards—are rehydrated and used to replicate the summer’s flavor. As the mixture thickens, butter is folded in until it melts and glazes the entire dish, lending it a silky finish and a delicious aroma.

Balay strikes a delicate balance between sweet and savory. The apricots provide fruity brightness, while the butter adds richness and depth. Sometimes, locals enhance it with a touch of crushed walnuts or dried mulberries, making it even more nourishing.

Served hot and shared from communal bowls, Balay is:

-

A breakfast favorite on freezing mornings

-

A recovery meal after long treks or physical labor

-

A comfort food during illness or after fasting

This dish reflects the efficiency and ingenuity of mountain cuisine: taking minimal ingredients, all sourced locally, and turning them into a hearty, calorie-rich meal that sustains the body in extreme climates. Its ingredients also showcase the deep cultural attachment to apricots, considered not just a fruit, but a gift of health and energy.

Balay is a reminder that in Northern Pakistan, food is not just sustenance—it is medicine, heritage, and warmth in a bowl.

8. Diram Phitti – Sweet Bread with a Twist

Up in the high-altitude valleys of Gilgit-Baltistan, where winter routines demand high-energy sustenance, Diram Phitti holds a cherished spot at the table. This sweet, wholesome bread is made from sprouted wheat flour, a traditional preparation method that not only enhances the flavor but also amplifies its nutritional profile.

The wheat grains are first germinated over several days, a process that activates enzymes and increases the bioavailability of nutrients like iron, B-vitamins, and natural sugars. Once sprouted, the grains are dried and ground into flour, which is then mixed with water or milk, often enriched with a bit of salt, and sometimes lightly fermented.

Unlike the more familiar flatbreads of the plains, Diram Phitti is thicker, denser, and subtly sweet. It can be:

-

Baked in clay ovens (tandoor)

-

Pan-cooked on flat iron griddles

-

Brushed with ghee or butter for added richness

Its taste resembles a cross between whole grain bread and molasses cake, making it deeply satisfying without being overly sugary. The texture is moist and hearty, ideal for those cold days when energy expenditure is high and nutrients are in demand.

Diram Phitti is often served:

-

At family breakfasts, paired with apricot jam or tea

-

During festive occasions, weddings, and winter gatherings

-

As a travel ration, thanks to its long shelf life and dense caloric value

It is deeply symbolic of the mountain philosophy of food—nothing fancy, but everything intentional. Each ingredient serves a purpose, and each bite tells a story of resourcefulness, health, and warmth.

This is not just bread. Diram Phitti is a gift of tradition, passed from one generation to the next, from mountain to hearth.

9. Propoo – Barley Dumplings with Apricot Seed Sauce

Among the many hearty dishes of Baltistan, Propoo stands out as a culinary embodiment of mountain resilience and resourcefulness. This rustic yet sophisticated dish features barley flour dumplings, carefully shaped by hand, and topped with a deeply flavorful sauce made from apricot seeds and apricot oil, both locally sourced and seasonally preserved.

Barley flour, known for its coarse texture and nutty taste, is mixed with water and a pinch of salt to form a firm dough. The dumplings are then steamed or boiled until tender. The real magic, however, lies in the topping: apricot kernels, extracted from sun-dried pits, are roasted and crushed into a fine paste. This is combined with golden apricot oil, resulting in a nutty, slightly bitter, aromatic sauce poured generously over the dumplings.

The flavor profile of Propoo is unlike anything else:

-

Earthy from the barley

-

Rich from the apricot oil

-

Bittersweet and bold from the seed paste

This dish is a Balti winter essential, often served during long, snowbound months when energy-rich, warming foods are necessary for survival. It’s also a cultural symbol—a showcase of how nothing goes to waste in the highlands. Even the stone-like pits of apricots are repurposed into culinary gold.

Beyond flavor and nutrition, Propoo represents the inventiveness of indigenous cooking, where local ingredients are elevated into layered, memorable meals. It’s the kind of dish that tells a story—from orchard to table, from grain to garnish.

10. Glacier-Fed Organic Produce – Powered by Nature

One of the least-known but most powerful secrets behind the incredible taste and quality of Northern Pakistan’s food lies beneath its surface—glacier-fed water. In regions like Hunza, Nagar, and Ghizer, fruits and vegetables are grown using meltwater from the surrounding glaciers. This pure, mineral-rich irrigation nourishes crops in a way that is almost impossible to replicate elsewhere.

The result? Organic produce with unmatched flavor, density, and shelf life.

Apricots, apples, cherries, mulberries, tomatoes, and leafy greens all flourish in these highland farms. Because of the clean water, chemical-free soil, and high UV exposure, these fruits and vegetables develop:

-

More concentrated nutrients

-

Stronger natural sweetness

-

Brighter color and firmer texture

Unlike commercial farms that rely on pesticides or artificial fertilizers, most farmers in Northern Pakistan use time-tested organic techniques, composting naturally and planting in harmony with the seasons. Produce is often picked at peak ripeness and consumed locally, preserving both its taste and nutritional integrity.

What makes glacier-fed farming particularly special is that it supports a closed-loop ecosystem:

-

The glaciers feed the fields

-

The fields feed the people

-

The people protect the glaciers

This delicate cycle is both sustainable and sacred, forming the backbone of Northern Pakistan’s culinary identity. For travelers, tasting produce in Hunza or Skardu is more than a farm-to-table experience—it’s mountain-to-mouth, infused with mineral-rich water, ancestral wisdom, and natural purity.

Also See: Indulge in Pakistan’s Desserts

References

-

Intentional Detours – Hunza Food Guide

Explores glacier-fed farming, apricot production, and organic food traditions in Hunza.

🔗 https://intentionaldetours.com/hunza-food-guide/ -

Skardu Trekkers – Northern Pakistan Food Guide

Covers regional dishes like Mamtu, Propoo, yak dairy, and sun-dried mulberries across Gilgit and Skardu.

🔗 https://skardutrekkers.com/northern-pakistan-food/ -

PakVoyager – Traditional Food of Hunza Valley

Details ingredients like Burus and their role in local cuisine, including cultural practices around food.

🔗 https://www.pakvoyager.com/news/hunza-valley-traditional-food -

Epic Expeditions – Food in Northern Pakistan

Highlights barley-based foods like Propoo, the significance of regional grains, and sustainable food systems.

🔗 https://epicexpeditions.co/blog/food-in-pakistan/ -

Real Pakistan – Local Cuisine of the Northern Areas

Offers insights into dishes like Balay and how they serve nutritional and cultural functions in mountain life.

🔗 https://realpakistan.com.pk/local-cuisine-of-the-northern-areas-a-culinary-journey/