1. Pakistan’s Coastal Geography and Marine Ecosystems

Picture by: https://www.worldwildlife.org/

Pakistan’s marine life flourishes along a diverse and ecologically rich coastline stretching approximately 1,050 kilometers, shared by the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan. This expansive stretch of the Arabian Sea holds immense ecological, economic, and strategic importance, forming the backbone of Pakistan’s Blue Economy.

A Mosaic of Marine Ecosystems

Pakistan’s coast hosts a remarkable range of marine ecosystems that support its biodiversity and sustain millions of livelihoods. These include:

-

Estuaries where rivers like the Indus meet the sea, creating nutrient-rich zones ideal for juvenile fish and crustaceans.

-

Mangroves, especially along the Indus Delta, serve as natural barriers against coastal erosion and breeding grounds for countless marine species.

-

Coral reefs, though limited in distribution, are critical biodiversity hotspots, found near islands like Astola and Churna.

-

Lagoons and mudflats that act as feeding and nesting areas for migratory birds and endangered turtles.

-

The continental shelf, which offers deep-sea habitats for larger marine species and plays a vital role in ocean productivity.

These interlinked zones form the base of the marine food web and are vital to sustaining Pakistan’s fisheries and coastal ecology.

The Exclusive Economic Zone: A Strategic Asset

Pakistan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) spans up to 200 nautical miles into the Arabian Sea. In 2015, the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf approved Pakistan’s claim for an extended continental shelf, increasing its jurisdiction from 200 to 350 nautical miles. This extension added nearly 50,000 square kilometers to Pakistan’s maritime territory, bringing the total to around 240,000 square kilometers.

This expanded zone significantly enhances Pakistan’s potential to explore and manage marine resources—from deep-sea fishing and aquaculture to offshore oil, gas, and mineral extraction.

Ecological Hotspots of National Importance

Several coastal habitats stand out for their biodiversity and ecological significance:

-

Astola Island (Balochistan): Pakistan’s first Marine Protected Area, home to rare coral species, nesting sea turtles, and migratory birds.

-

Churna Island (near Karachi): A vibrant site for coral communities and marine tourism, also vulnerable to overfishing and pollution.

-

Miani Hor Lagoon: A brackish water lagoon hosting unique mangrove ecosystems and serving as a key fish nursery.

These locations represent just a fraction of the coastal diversity that makes Pakistan a critical marine zone within the Northern Arabian Sea region. However, this diversity is increasingly under threat due to pollution, climate change, and unsustainable practices—a concern that deepens as we explore the next section on biodiversity.

2. Taxonomic and Biodiversity Richness in Marine Life

Picture by: https://www.graygroupintl.com/

Pakistan’s marine environment is a biological treasure trove, home to a wide variety of organisms ranging from microscopic plankton to massive marine mammals. The Marine Reference Collection and Resource Centre (MRCRC) at the University of Karachi has played a pivotal role in documenting this diversity. According to the comprehensive “Marine Faunal Diversity of Pakistan” inventory compiled by Dr. Quddusi B. Kazmi and collaborators, Pakistan’s coastline supports life from 22 different animal phyla, representing an estimated 100 million marine species—a figure that highlights the country’s immense biodiversity.

A Tapestry of Marine Life Forms

The waters of the Arabian Sea, bordering Pakistan, host numerous iconic and ecologically significant animal groups:

-

Mollusks: This group includes a wide range of species such as sea slugs, octopuses, and clams. Their presence indicates healthy sediment conditions and diverse habitats.

-

Echinoderms: Sea stars, sea cucumbers, and sea urchins are important benthic dwellers that contribute to nutrient cycling on the seafloor.

-

Cnidarians: This includes jellyfish, corals, and sea anemones—many of which are vital to coral reef ecosystems near islands like Churna and Astola.

-

Crustaceans: Crabs, lobsters, and shrimps form the backbone of Pakistan’s commercial fisheries.

-

Marine mammals: Occasional sightings of dolphins, whales, and porpoises near Pakistan’s offshore waters further highlight the ecological range of the marine ecosystem.

Each of these groups plays a unique role in maintaining the structure and function of marine ecosystems. Their presence also offers insight into the health and resilience of Pakistan’s coastal waters.

Hidden Treasures: Endemic and Rare Species

Many marine species found in Pakistan are endemic, meaning they are unique to this specific region and not found elsewhere in the world. Historical records, including colonial-era documentation from British India, combined with modern studies, indicate that several species have gone locally extinct or are rarely seen today due to overfishing, habitat loss, and pollution.

Some organisms have only been recorded once in over a century, often from offshore areas or lesser-explored ecosystems like methane seeps near Makran. This highlights not only the rich past of Pakistan’s marine life but also the urgent need for updated taxonomic research to track ongoing ecological changes.

Institutions Leading Marine Taxonomy and Conservation

Multiple scientific bodies are actively involved in documenting and protecting marine biodiversity in Pakistan:

-

The Marine Reference Collection & Resource Centre (MRCRC) at the University of Karachi serves as the central hub for marine taxonomic research, housing hundreds of thousands of species specimens.

-

WWF-Pakistan has played a vital role in field surveys, awareness campaigns, and community-led conservation programs.

-

Zoological Society of Pakistan and individual researchers like Dr. Quddusi B. Kazmi and Mr. Moazzam Khan have also contributed significantly to creating detailed species lists and highlighting marine biodiversity challenges.

Despite these efforts, large gaps remain in our knowledge—especially for deep-sea species, microscopic invertebrates, and ecological interactions. Strengthening Pakistan’s marine research infrastructure, along with digitalizing taxonomic data and training young scientists, is crucial for preserving this underwater legacy.

3. Sharks, Rays, and Large Species in Pakistani Waters

Picture by: https://pakistannationalfish.com/

Among the most iconic and ecologically vital members of Pakistan’s marine life are sharks and rays. These apex and mesopredators play a critical role in maintaining the balance of marine food chains, regulating fish populations, and ensuring the overall health of marine ecosystems. However, in Pakistan’s coastal waters—particularly in shark landing zones such as Karachi Fish Harbour, Korangi, Sonmiani, and Gwadar—these majestic species are facing growing threats from unsustainable fishing practices.

Shark Species Diversity in Pakistan

A landmark study conducted from 2017 to 2018 identified 41 shark species belonging to 11 families in Pakistan’s waters. The majority of these landings occurred at the Karachi Fish Harbour, which alone accounted for nearly 87% of all sharks landed during the survey. The most dominant families included:

-

Carcharhinidae (Requiem sharks) – comprising nearly half of the total catch and 23 of the recorded species.

-

Triakidae (Houndsharks) – contributing around 35% of shark landings.

-

Hemiscylliidae (Bamboo sharks) – with a 16% share, often found in reef-associated environments.

These families reflect the richness of the Arabian Sea ecosystem and the historical abundance of large predators. However, the alarming presence of immature and juvenile sharks in landings raises red flags about the long-term sustainability of these populations.

Bycatch and the Juvenile Crisis

One of the gravest conservation concerns is the unintentional capture of juvenile sharks and rays as bycatch in commercial fisheries. These young sharks, caught before they reach maturity, never get the chance to reproduce—creating a ripple effect that threatens entire species.

Pakistan lacks effective regulation or gear modification in most fisheries to avoid bycatch. The absence of size limits and nursery-area protections further compounds the problem. For slow-growing species like sharks, which have long gestation periods and few offspring, such exploitation can rapidly collapse populations.

International Protection Status: CITES and CMS

Many shark species found in Pakistani waters are already listed as threatened on international platforms:

-

85% of the landed shark species are classified as Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), Vulnerable (VU), or Near Threatened (NT) by the IUCN Red List.

-

Nine species of sharks are listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which requires trade regulations to avoid population decline.

-

Of these, eight are also included in the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) under Appendix II, indicating a need for international cooperation in their protection.

Despite these listings, Pakistan has yet to establish comprehensive national action plans or enforce trade restrictions in a consistent, enforceable manner.

Declining Trends and the Urgency to Act

Long-term data paints a troubling picture. From 1993 to 2019, Pakistan’s shark landings have shown a dramatic decline—from nearly 55,000 metric tons in 1999 to just 5,793 metric tons in 2019. This represents an almost 90% drop in landings over two decades, suggesting either a severe depletion of shark populations or a shift in fishing practices away from traditional shark fisheries.

Whatever the reason, this decline reflects a broader ecological imbalance and highlights the urgency for Pakistan to implement science-based conservation measures—such as shark sanctuaries, gear restrictions, and monitoring of trade.

4. Coral Reefs and Sensitive Habitats

Picture by: https://irverde.com.pk/

While coral reefs occupy only a small fraction of Pakistan’s coastline, their ecological importance cannot be overstated. These delicate marine structures are biodiversity hotspots—providing food, shelter, and breeding grounds for countless marine species. In Pakistan, coral reefs are primarily found around Astola Island, with smaller patches along the Gwadar coast and near Churna Island, though many of these are under serious environmental stress.

Fragile Distribution and Limited Coverage

Pakistan’s coral reef presence is relatively limited, concentrated in specific zones that offer favorable conditions such as clear water, rocky substrates, and reduced turbidity. Among the most notable locations are:

-

Astola Island (off the coast of Balochistan): Designated as Pakistan’s first Marine Protected Area (MPA) in 2017, it supports a range of coral species, reef fish, mollusks, and nesting sea turtles.

-

Churna Island (near Karachi): Known for its scuba diving and marine tourism potential, Churna hosts a semi-pristine reef ecosystem but remains vulnerable to unregulated activity.

-

Gwadar Bay and Ormara: These areas contain scattered coral patches that are being increasingly affected by sediment runoff and port-related development.

Due to their patchy distribution and lack of widespread monitoring, these coral zones remain poorly documented and often overlooked in marine conservation efforts.

Impacts of Sedimentation, Overfishing, and Pollution

The survival of coral reefs in Pakistan is under threat from multiple overlapping stressors, many of which are anthropogenic:

-

Sedimentation from coastal development, deforestation, and dredging smothers coral polyps and blocks sunlight essential for photosynthesis.

-

Overfishing, particularly of herbivorous species like parrotfish, disrupts the ecological balance and contributes to algae overgrowth on coral surfaces.

-

Marine pollution, especially plastic waste and chemical runoff from agriculture and industry, leads to disease outbreaks and weakens coral resilience.

These pressures reduce coral cover, degrade reef structure, and lead to biodiversity loss within the ecosystem. Additionally, the absence of enforced conservation regulations has allowed destructive practices—such as anchor damage and unsustainable tourism—to persist unchecked.

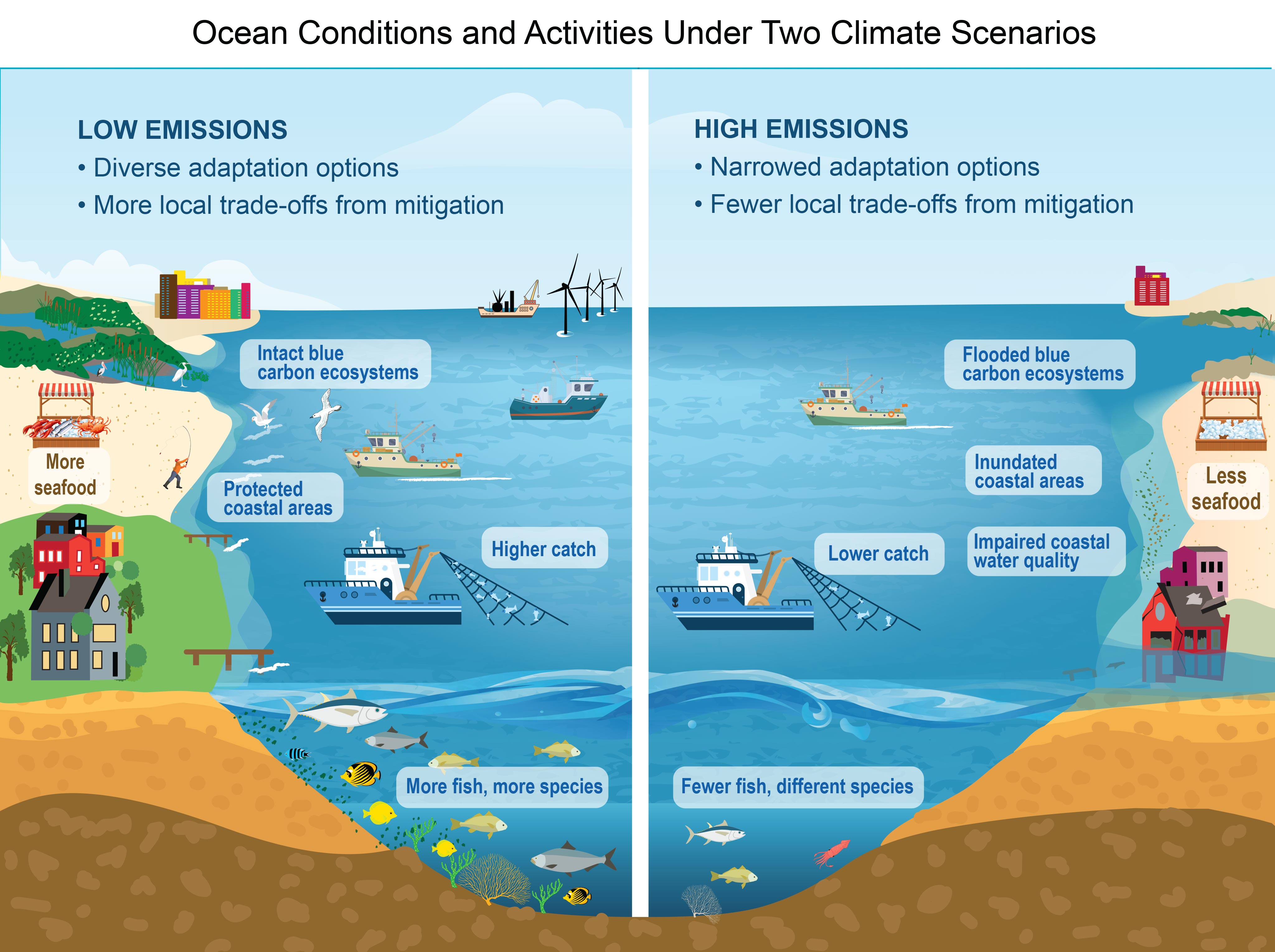

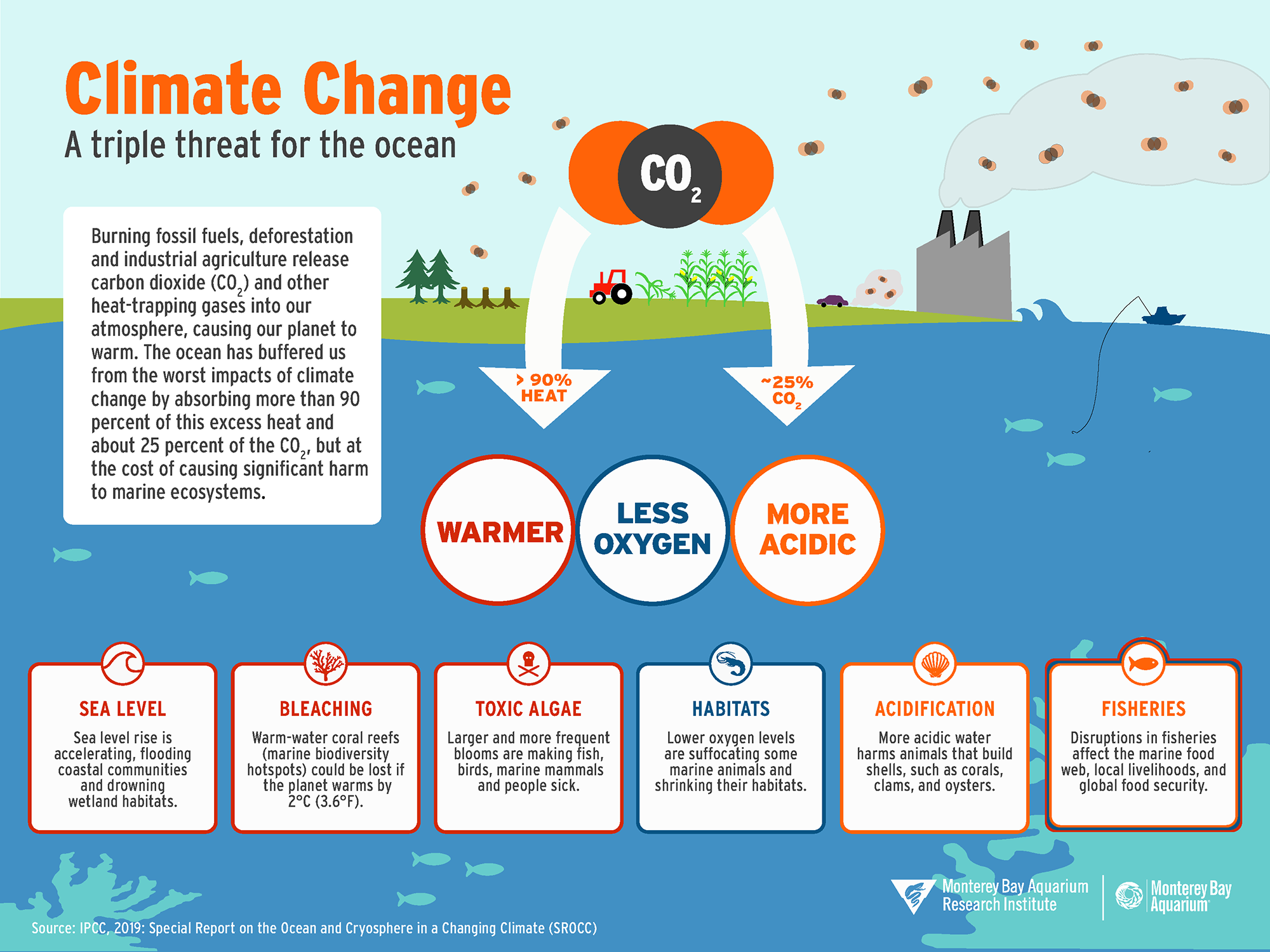

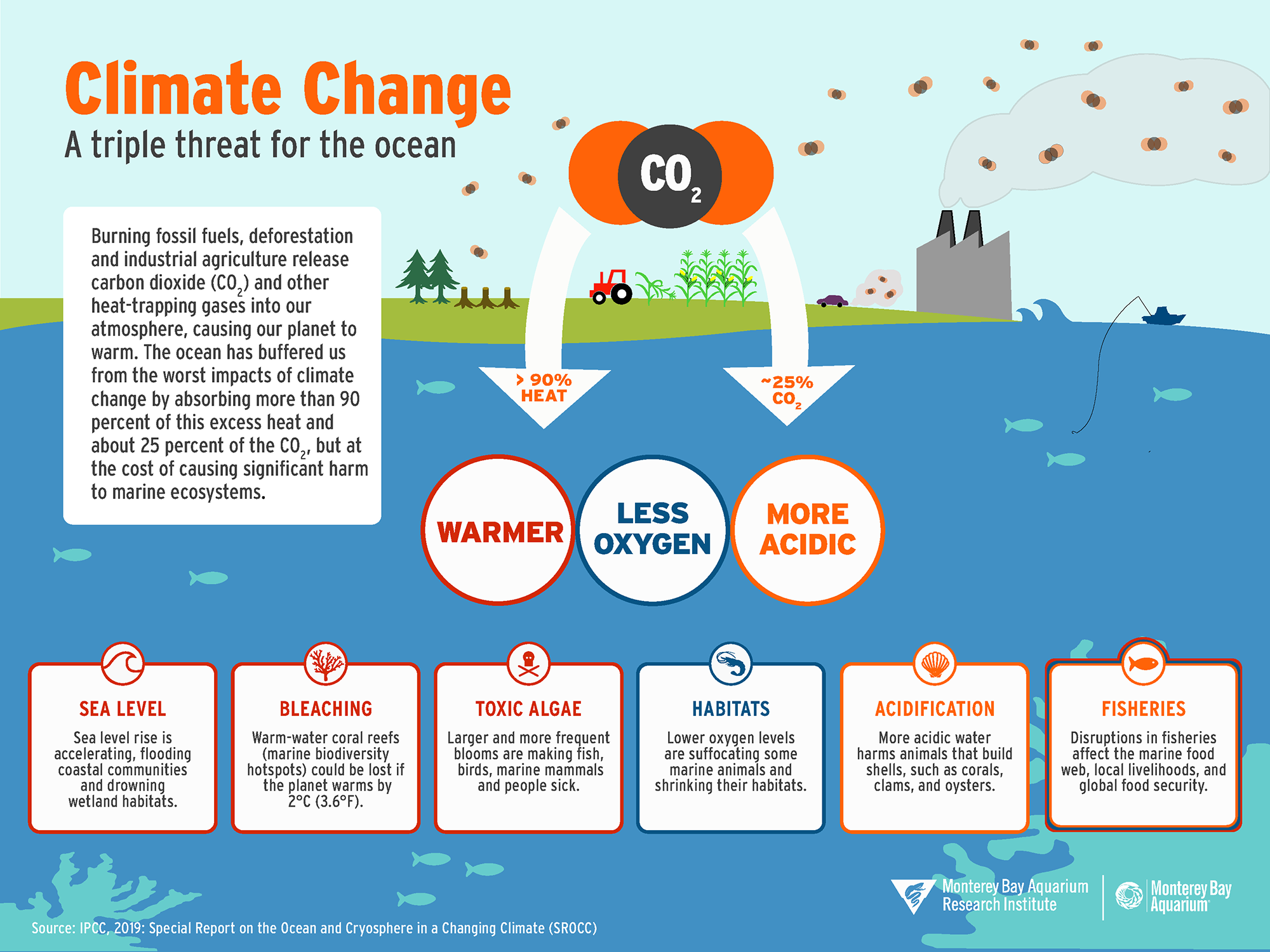

Climate Change and Coral Bleaching

Rising sea temperatures are an existential threat to coral reefs globally, and Pakistan is no exception. Marine heatwaves (MHWs), which have become more frequent in the Arabian Sea, cause coral bleaching—a phenomenon where corals expel the symbiotic algae that give them color and nutrients. Bleached corals are more susceptible to disease and mortality.

Along with temperature stress, ocean acidification is gradually altering the chemical composition of seawater, making it harder for corals to build their calcium carbonate skeletons. These climate-driven impacts, combined with local pressures, have led to a noticeable decline in reef health in Pakistan’s coral zones over the past two decades.

Pathways for Restoration and Protection

To safeguard Pakistan’s coral ecosystems, a multi-pronged conservation approach is essential. This includes:

-

Coral Restoration Projects: Initiatives such as coral nurseries and artificial reefs should be piloted in areas like Churna and Astola to promote regrowth and habitat recovery.

-

Expansion of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): Currently, only Astola Island holds formal MPA status. More reef zones must be surveyed and brought under legal protection with active enforcement.

-

Sustainable Reef Tourism Regulation: Dive tourism can support conservation when properly managed. Training operators, restricting anchor zones, and capping tourist footfall are key steps.

-

Community and Scientific Collaboration: Engagement of coastal communities in monitoring and protection, supported by institutions like WWF-Pakistan and the University of Karachi, is vital for long-term success.

If implemented earnestly, these measures can ensure that Pakistan’s coral reefs not only survive but regenerate, sustaining marine life and supporting coastal economies for generations to come.

5. Human-Induced Threats to Marine Life

Picture by: https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/

The richness of marine life along Pakistan’s coastline stands in stark contrast to the environmental degradation caused by unchecked human activities. From the bustling ports of Karachi to the remote shores of Balochistan, coastal waters are being increasingly polluted—threatening ecosystems that have existed for centuries. The primary drivers of this damage are rooted in industrial waste, untreated sewage, plastic pollution, oil spills, and agricultural runoff, all of which combine to weaken marine biodiversity and diminish the ecological value of Pakistan’s maritime zones.

Karachi Harbour: A Pollution Epicenter

Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city and industrial hub, also serves as a critical maritime center. However, it has become one of the most polluted marine zones in South Asia. Every day, approximately 471 million gallons of untreated municipal sewage and thousands of metric tons of solid waste are discharged into the sea, with a significant portion funneled directly into Karachi Harbour.

Much of this waste originates from:

-

Residential areas with poor sanitation infrastructure

-

Industrial zones with no wastewater treatment

-

Illegal dumping along coastal streams and nullahs

The result is a toxic mixture of heavy metals, chemicals, and pathogens that disrupt marine food chains, damage fish reproductive systems, and render coastal waters unsafe for both wildlife and human use. The Greater Karachi Sewerage Plan, proposed years ago, remains largely unimplemented—deepening the crisis.

Plastic Pollution and Eutrophication

Globally, over 10 million metric tons of plastic enter oceans each year, and Pakistan is among the major contributors in the region. Plastic bottles, shopping bags, fishing nets, and microplastics have been found littering beaches, clogging mangroves, and even entering the digestive tracts of marine animals. These plastics do not biodegrade and often release toxic chemicals as they break down.

Alongside this, eutrophication—caused by nutrient runoff from fertilizers and domestic waste—leads to algal blooms that deplete oxygen levels in the water. Such hypoxic zones suffocate marine organisms, resulting in “dead zones” where biodiversity collapses. When coupled with sedimentation and temperature stress, these factors cause irreversible damage to delicate ecosystems such as coral reefs and estuaries.

Oil Spills, Ship Waste, and Agricultural Runoff

Pakistan’s growing maritime trade also brings with it a rise in oil spills and ship-generated pollution. The 2003 Tasman Spirit oil spill in Karachi, which released nearly 30,000 tons of crude oil, remains one of the country’s worst marine disasters. Its impacts were felt for years, affecting fish populations, mangroves, and human health in surrounding communities.

Routine shipping activities contribute to:

-

Discharges of bilge water contaminated with fuel and chemicals

-

Dumping of garbage and sewage

-

Underwater noise pollution that disturbs marine mammals

In addition, agricultural runoff—laden with pesticides and fertilizers—flows into rivers and eventually reaches the coast. This contaminates fish habitats and threatens food safety, particularly for species consumed by local communities.

Biodiversity Loss: The Karachi Case Study

Karachi serves as a sobering example of how urban expansion without environmental regulation can accelerate marine ecosystem collapse. Research indicates a significant decline in biodiversity along the city’s coastlines, including reduced sightings of fish, crustaceans, and mollusks in historically rich areas like Manora Channel and Sandspit backwaters.

Moreover, the degradation of mangroves, coral habitats, and estuaries due to pollution has weakened the city’s natural defenses against coastal flooding and erosion. What once served as nurseries and safe zones for marine life are now struggling to survive under layers of waste and toxicity.

If no action is taken, Karachi could lose much of its remaining marine biodiversity in the coming decades—a loss that would ripple across fisheries, tourism, and public health.

Also See: Climate Change & Deforestation

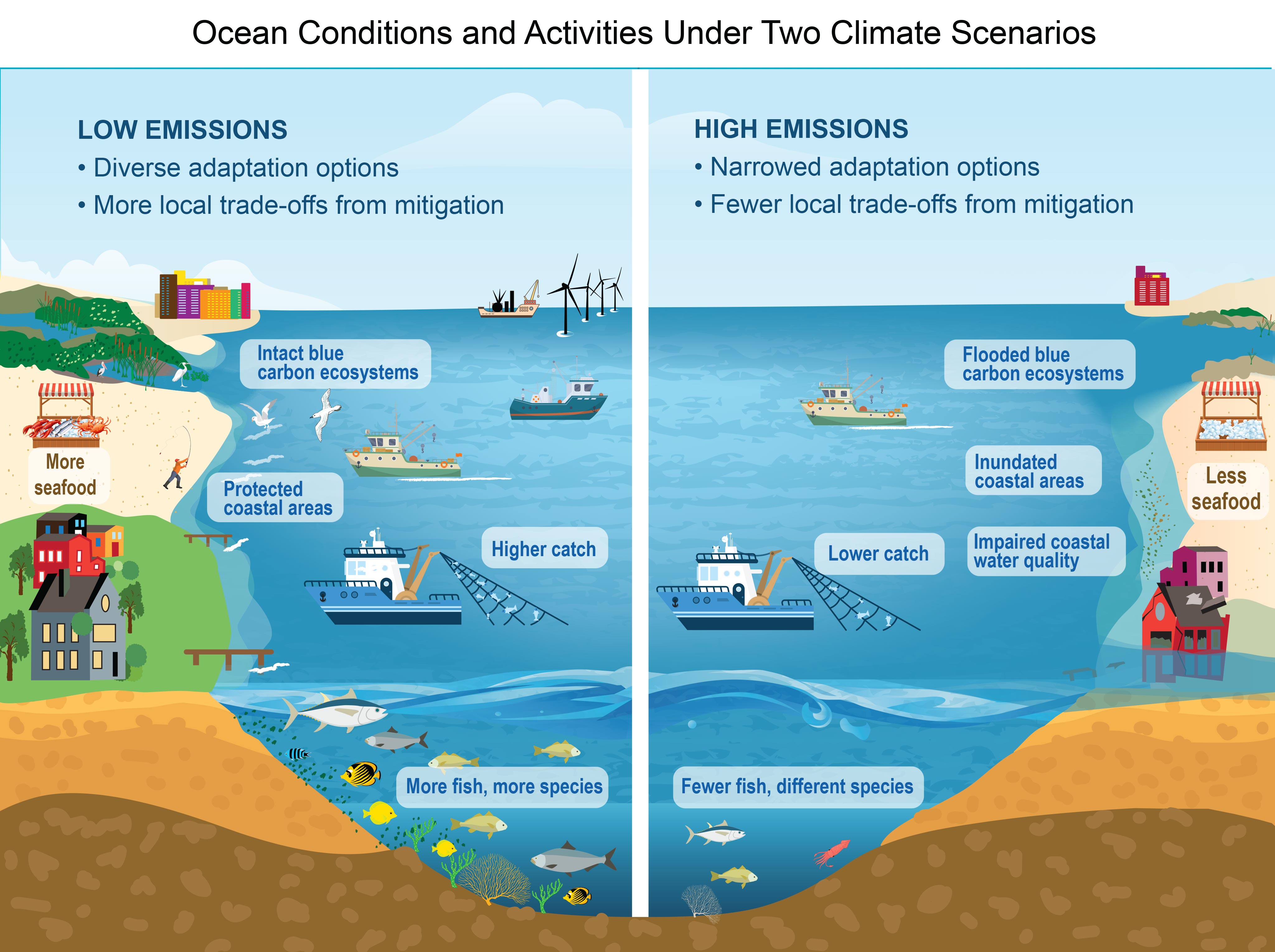

6. Climate Change and Marine Life Vulnerability

Picture by: https://www.mbari.org/

Climate change has become one of the most pressing non-traditional threats to Pakistan’s marine life. Rising temperatures, ocean acidification, and erratic weather patterns are no longer abstract future possibilities—they’re already impacting the country’s coastal ecosystems and the communities that depend on them. As global warming accelerates, its effects on marine species, habitats, and livelihoods are becoming increasingly visible along Pakistan’s shoreline, especially in the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan.

Marine Heatwaves and Warming Waters

One of the clearest indicators of climate change in marine systems is the rise in sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and the occurrence of Marine Heatwaves (MHWs)—prolonged periods of unusually warm ocean conditions. These heatwaves can drastically affect the survival of temperature-sensitive organisms, particularly corals, plankton, and fish larvae.

In Pakistan, MHWs in the Arabian Sea have led to:

-

Disruption of fish spawning cycles

-

Migration of fish species to deeper or cooler waters

-

Stress and bleaching of coral reefs in Astola and Churna Island

Such changes not only reduce biodiversity but also impact the availability of commercial fish stocks, hurting local fisheries and seafood supply chains.

Coral Bleaching and Ocean Acidification

Warming waters have a direct effect on coral reef ecosystems. When ocean temperatures rise beyond a certain threshold, corals undergo bleaching, losing the symbiotic algae that provide them with energy and vibrant color. While some corals can recover from brief heat stress, prolonged exposure can lead to permanent damage or death.

Simultaneously, increased levels of carbon dioxide (CO₂) in the atmosphere are being absorbed by the ocean, altering its pH balance in a process known as ocean acidification. This reduces the availability of calcium carbonate—an essential compound that corals and shellfish need to build their skeletons and shells.

The result is a double threat: corals are both weakened by heat and less able to rebuild, pushing reef ecosystems closer to collapse.

Impact on Coastal Livelihoods

The consequences of climate-induced marine disruption are particularly severe for communities in Sindh and Balochistan, where many people rely on fishing, aquaculture, and coastal tourism for income. Changes in fish migration patterns have already led to declining catches for small-scale fishers, increasing economic insecurity in villages along the Indus Delta and the Makran coast.

Additionally, extreme weather events—such as cyclones, coastal flooding, and saline intrusion—have become more frequent and intense, damaging infrastructure and displacing coastal populations. These events directly affect the resilience of local economies and undermine long-standing marine-dependent livelihoods.

Gaps in Policy and Adaptive Capacity

Despite the evident threats, Pakistan’s national climate policy response still lacks a targeted marine component. While the country is a signatory to international frameworks such as the Paris Agreement and has produced national climate adaptation strategies, there is minimal emphasis on marine-specific risks or resilience planning.

Critical gaps include:

-

Lack of early warning systems for marine heatwaves and ocean anomalies

-

Inadequate integration of marine science in national climate planning

-

No localized adaptation plans for coastal fishing communities

-

Poor coordination between environmental, maritime, and fisheries agencies

Without decisive action, the long-term impact of climate change could irreversibly alter Pakistan’s coastal ecosystems and compromise national food security, economic stability, and biodiversity conservation.

Listen to the Podcast

7. Gaps in Governance, Policy & Public Awareness

Despite the ecological and economic importance of marine life in Pakistan, there remains a substantial disconnect between environmental policy on paper and action on the ground. Although the country is party to numerous international environmental agreements and has introduced national regulations for marine conservation, the implementation remains weak, coordination fragmented, and public awareness limited.

Legal Frameworks with Limited Impact

Pakistan is a signatory to major international conventions aimed at protecting marine ecosystems:

-

UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea) grants Pakistan jurisdiction over its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and obligates it to prevent marine pollution.

-

MARPOL (International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships) sets international standards for ship-based pollution control.

-

The London Convention restricts dumping of harmful waste into the sea.

While these frameworks offer strong legal backing, enforcement at the national level is sporadic. Regulatory bodies often lack the capacity, resources, or political backing to ensure compliance—especially in heavily industrialized zones like Karachi Harbour. Violations related to untreated waste disposal, plastic dumping, and oil discharge frequently go unchecked.

Monitoring and Surveillance Deficiencies

An effective conservation system requires real-time monitoring of water quality, pollution levels, and biodiversity indicators, but Pakistan currently lacks the infrastructure to carry this out consistently. There is no national database or public dashboard that provides updates on marine health indicators such as pH levels, chemical concentrations, or marine species sightings.

Moreover, Pakistan’s Environmental Protection Agencies (EPAs) are underfunded and largely reactive rather than preventive. In the absence of satellite surveillance, automated data buoys, or remote sensing technologies, authorities are unable to detect or act upon emerging environmental threats until after significant damage has already occurred.

Disjointed Institutional Response

Another major governance hurdle lies in the poor coordination between agencies. Marine affairs in Pakistan are spread across multiple ministries and departments—including climate change, maritime affairs, fisheries, defense, and environment. This overlapping jurisdiction often leads to:

-

Policy duplication or contradiction

-

Delayed enforcement

-

Fragmented data collection and reporting

For example, the Pakistan Navy may be monitoring illegal maritime activity, while the Ministry of Climate Change works on conservation programs, yet both may operate independently without data-sharing mechanisms or collaborative platforms.

The absence of a central marine governance authority or unified national strategy leaves gaps that are exploited by polluters and ignored by industries, further endangering marine ecosystems.

Public Awareness and Community Engagement

Lastly, the role of public education and grassroots participation in marine conservation is still underestimated. In many coastal areas, communities are unaware of the long-term consequences of pollution, overfishing, or coral destruction. Educational outreach on marine life is virtually non-existent in school curricula, mainstream media, or religious platforms that influence social behavior.

To address this, there is a critical need to:

-

Launch green education campaigns targeting youth, fishers, industrial workers, and port users

-

Incorporate marine awareness modules into school and university programs

-

Promote community-based conservation projects through NGOs and local government bodies

-

Train volunteers and citizen scientists to monitor and report on marine health

Creating a conservation culture requires more than just laws—it needs ownership and participation from the public, especially those living closest to the sea. Without it, policy reforms will fall short of achieving real, lasting change.

8. Towards Sustainable Marine Life Protection in Pakistan

Pivture by: https://iips.com.pk/

As the threats facing Pakistan’s marine life become increasingly urgent and multifaceted, the path forward lies in embracing sustainability through science, governance, community engagement, and innovation. Protecting our oceans isn’t only about preserving biodiversity—it’s about safeguarding food security, climate resilience, cultural identity, and economic potential for generations to come.

Expanding and Strengthening Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

One of the most effective global strategies for marine conservation has been the establishment of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). These zones restrict damaging activities like trawling, dumping, and uncontrolled tourism, giving marine ecosystems space to regenerate naturally.

Pakistan’s first and only official MPA, Astola Island, marked an important starting point, but many ecologically sensitive regions remain unprotected. Potential priority sites for future MPAs include:

-

Churna Island – Home to coral reefs, reef fish, and threatened species; heavily impacted by unregulated tourism.

-

Miani Hor Lagoon – A vital nursery ground for fish and crustaceans, with mangrove and estuarine diversity.

-

Gwadar and Ormara coastlines – Known for sea turtle nesting, seagrass beds, and high biodiversity.

Expanding MPAs, along with clearly defined boundaries and community-backed enforcement, can yield tangible ecological recovery within just a few years.

Learning from Global Success Stories: A Green Theory Approach

The Green Theory Perspective, which prioritizes ecological balance over human-centered exploitation, offers valuable guidance. Countries like Denmark, Indonesia, and South Africa have successfully demonstrated how marine conservation can work when grounded in holistic thinking and public participation.

-

Denmark invests in marine monitoring technologies and incentivizes sustainable aquaculture.

-

Indonesia has developed an extensive network of MPAs, backed by local co-management and enforcement.

-

South Africa integrates marine spatial planning with community development and ecotourism.

These examples show that with political will, scientific input, and inclusive governance, developing countries like Pakistan can protect their marine resources without compromising growth.

Empowering Communities and Citizen Scientists

Marine life conservation cannot succeed without the active participation of coastal communities. Fishers, boat operators, divers, and even school students can become stewards of the ocean if given the tools and training.

-

Community-led monitoring projects can help track illegal activities, report stranded animals, or document biodiversity shifts.

-

Citizen science initiatives, such as reef check programs or beach cleanups, raise awareness while generating valuable ecological data.

-

NGOs and universities can support locals in developing low-tech conservation tools—such as handmade artificial reefs or pollution traps.

Building a sense of ownership among local populations ensures that conservation measures are not only top-down but grounded in community knowledge and trust.

Unlocking the Potential of the Blue Economy

Sustainable marine life protection is not a financial burden—it is an investment in the Blue Economy, a model that promotes economic growth through ocean resources while preserving their ecological integrity.

For Pakistan, this means:

-

Ecotourism: Guided snorkeling, mangrove trails, and turtle-watching tours can offer livelihoods while educating tourists.

-

Sustainable fisheries: Transitioning to regulated catch sizes, seasonal bans, and selective fishing gear protects stocks while maintaining income for fishers.

-

Marine biotechnology: Exploring medicinal compounds from sponges, algae, and marine microbes can open new frontiers in health and research.

These sectors, if developed responsibly, can transform Pakistan into a regional leader in marine conservation and innovation.

Resources

-

Ahmad, I. et al. (2024). Coral Reefs of Pakistan: A Comprehensive Review of Anthropogenic Threats, Climate Change, and Conservation Status. Frontiers in Marine Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1466834

-

Javed, A. et al. (2024). Shark (Elasmobranchs) Fisheries Trend in Pakistan: Species Composition and Conservation Status. Pakistan Journal of Zoology. DOI:10.17582/journal.pjz/20230612060631

-

Kazmi, Q.B. (2022). Marine Faunal Diversity of Pakistan: Inventory and Taxonomic Resources. Zoological Society of Pakistan.

-

Sheikh, H.G. & Hameed, G. (2024). Maritime Pollution in Pakistan and Its Impact on Marine Life: Challenges and Way Forward. Journal of Water Resources and Ocean Science, Vol. 13(3), pp. 84-93. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.wros.20241303.13

-

Baig, N. & Askari, M.U. (2024). Marine Pollution in The Maritime Zones of Pakistan: A Green Theory Perspective. Annals of Human and Social Sciences, Vol. 5(1), pp. 159–172.

-

Ali, S.H. (2023). Global Warming and Its Impact on Marine Life in Pakistan: Causes and Concerns. International Journal of Contemporary Issues in Social Sciences, Vol. 2(4), pp. 1301–1308.

-

ALS Journal (2023). Marine Life & Fish Management: An Effective Tool of Blue Economy of Pakistan. https://submission.als-journal.com/index.php/ALS/article/view/1540

-

Valiela, I. (2008). Eutrophication and Marine Ecosystems. Ocean & Coastal Management, Vol. 51(7), pp. 429–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2008.01.004

-

WMU Dissertations. (2013). Environmental Issues in Coastal Waters: Pakistan as a Case Study. World Maritime University, Malmö, Sweden. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/201

-

Springer. (1993). Natural and Human Threats to Biodiversity in the Marine Ecosystem of Coastal Pakistan. In: Biodiversity Conservation in Managed Forests and Protected Areas. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-017-1066-4_17

-

OSTI. (2011). Bio Screening of Marine Organisms from the Coasts of Pakistan. https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/21592418