The Economic Backbone: Rivers Fueling Pakistan’s Agriculture and Industry

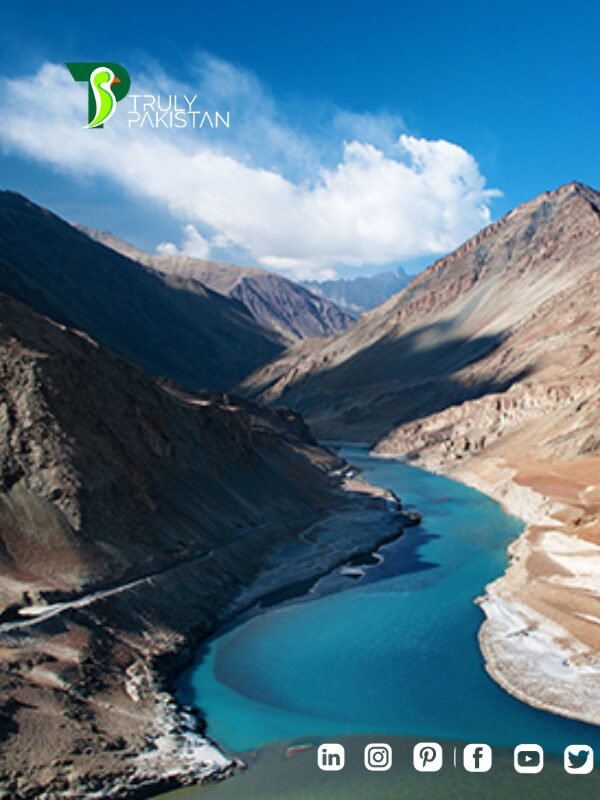

Picture by: https://www.dawn.com/

In Pakistan, rivers are not merely flowing bodies of water — they are the arteries of the nation’s economy. Among them, the Indus River System stands as a testament to nature’s ability to sustain civilizations, economies, and ecosystems over millennia. From transforming arid lands into fertile fields to driving energy production and supporting livelihoods, rivers are deeply embedded in every facet of Pakistan’s socio-economic framework.

The Indus River System: Turning Deserts into Breadbaskets

Spanning over 3,180 kilometers, the Indus River is Pakistan’s lifeline, weaving through mountains, plains, and deserts before meeting the Arabian Sea. Fed by glaciers from the Himalayas, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush ranges, it forms the backbone of the Indus Basin, joined by five key tributaries — Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas.

This river system is responsible for transforming over 16 million hectares of otherwise arid and semi-arid land into some of the most fertile plains in South Asia. According to studies, nearly 90% of Pakistan’s agricultural output depends directly on water sourced from this basin. Without these rivers, Pakistan’s agrarian economy would collapse, as rainfall alone cannot sustain large-scale farming due to the country’s predominantly dry climate.

Moreover, the seasonal flow of the Indus — governed by glacial melt and monsoon rains — ensures cyclical replenishment of soil nutrients, naturally supporting crop cycles that have fed civilizations for thousands of years.

Irrigation Networks: Sustaining the Agricultural Heartland

Pakistan is home to the world’s largest contiguous irrigation system — the Indus Basin Irrigation System (IBIS). This colossal network comprises:

- Over 58,500 kilometers of canals.

- More than 107,000 watercourses.

- Numerous barrages, headworks, and link canals.

The IBIS diverts river water across Punjab, Sindh, parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan, enabling the cultivation of essential crops. It supports:

- Wheat and rice — the staple foods ensuring national food security.

- Cotton — the backbone of Pakistan’s textile industry, which contributes over 60% of the country’s exports.

- Sugarcane — vital for both consumption and industrial processing.

However, this heavy reliance on river-fed irrigation has also led to challenges like waterlogging and salinity, affecting nearly 2 million hectares of agricultural land. Sustainable management of river resources is therefore critical, not just for productivity but for the long-term viability of Pakistan’s farmlands.

Hydropower Generation: Energizing the Nation

Rivers in Pakistan do more than irrigate—they power industries and households. The kinetic energy of flowing water is harnessed through major dams such as:

- Tarbela Dam — one of the world’s largest earth-filled dams.

- Mangla Dam — critical for both irrigation and power generation.

- The upcoming Diamer-Bhasha Dam, projected to add 4,500 MW to the national grid.

Hydropower currently contributes around 30-35% of Pakistan’s electricity generation capacity. This renewable energy source is vital in reducing dependency on imported fossil fuels, curbing energy costs, and lowering carbon emissions.

Despite this potential, Pakistan is utilizing only a fraction of its estimated 60,000 MW hydropower capacity. Expanding river-based energy projects, while balancing ecological concerns, remains a key strategy for addressing the country’s chronic energy shortages.

Fisheries and Livelihoods: Rivers as a Source of Sustenance

Beyond agriculture and energy, rivers support a vibrant yet underappreciated sector — inland fisheries. The Indus River and its network of canals, lakes, and floodplains harbor a diverse range of freshwater species, including Rohu, Catla, and Mrigal.

Inland fisheries contribute significantly to:

- Food security, providing affordable protein to rural populations.

- Employment, supporting over 400,000 fishermen and associated workers across Pakistan.

- Local economies through fish markets, processing units, and small-scale export activities.

Seasonal flooding of rivers creates temporary wetlands and floodplain lakes, which act as natural breeding grounds for fish. However, declining water quality, overfishing, and habitat loss threaten these ecosystems, putting both biodiversity and human livelihoods at risk.

For countless riverine communities, especially in Sindh and southern Punjab, rivers are not just a resource — they are a way of life. From transportation and agriculture to cultural identity and sustenance, these waters shape daily existence.

Biodiversity Hotspots: Rivers as Ecological Corridors

Picture by: https://www.researchgate.net/

Pakistan’s rivers are more than lifelines for human survival—they are dynamic ecosystems that nurture an extraordinary range of biodiversity. Flowing from the snow-capped peaks of the north to the coastal plains of the south, these rivers serve as ecological corridors, ensuring connectivity between habitats and supporting species that are vital to environmental stability.

Habitat for Flora and Fauna: Lifelines for Wildlife

The landscapes surrounding Pakistan’s rivers are teeming with life. Riverbanks, floodplains, and adjacent wetlands create a mosaic of habitats that support both aquatic and terrestrial species. These areas are critical for breeding, feeding, and migration, forming the backbone of Pakistan’s natural heritage.

A flagship species highlighting this ecological richness is the Indus River Dolphin (Platanista gangetica minor). Listed as endangered by the IUCN, this unique cetacean is endemic to the lower Indus and serves as an indicator of river health. Once widespread, its population has dwindled due to habitat fragmentation and declining water quality.

In addition to the dolphin, Pakistan’s river ecosystems host:

- Over 180 species of freshwater fish, many of which are crucial for both ecological balance and local fisheries.

- Numerous amphibians and reptiles, including species adapted specifically to riverine environments.

- Diverse riparian vegetation that stabilizes riverbanks, reduces erosion, and provides habitat for insects, birds, and mammals.

Studies emphasize that these biodiverse zones act as buffers against environmental shocks, supporting ecosystem resilience in the face of climate variability.

Wetlands and Floodplains: Nature’s Water Filters and Buffers

Pakistan’s wetlands, sustained by river systems, are internationally recognized for their ecological value, with 19 Ramsar sites covering over 1.3 million hectares. Key sites like Haleji Lake, Keenjhar Lake, and Uchhali Wetlands Complex are biodiversity hotspots, supporting rare and migratory species.

These wetlands deliver critical ecosystem services:

- Water purification: Acting as natural filtration systems, they absorb pollutants, sediments, and excess nutrients, improving downstream water quality.

- Flood mitigation: By absorbing seasonal floodwaters, wetlands protect human settlements and agricultural lands from destructive inundations.

- Groundwater recharge: Wetlands play a silent but crucial role in maintaining aquifer levels, ensuring water availability during dry seasons.

However, unchecked urbanization, pollution, and reduced river inflows are shrinking these wetlands, threatening the species that depend on them and increasing the risk of floods and droughts.

Indus Delta and Mangrove Forests: Guardians of the Coastline

The Indus Delta—one of the largest arid zone deltas in the world—hosts extensive mangrove forests, which are vital for coastal biodiversity and protection. Historically spanning over 600,000 hectares, these mangroves have been severely reduced due to decreased freshwater flow, upstream damming, and encroachment.

Mangroves provide:

- Nurseries for marine life, supporting Pakistan’s coastal fisheries by offering breeding grounds for shrimp, fish, and shellfish.

- Natural defense mechanisms, shielding coastal communities from cyclones, tidal surges, and erosion.

- Significant contributions to carbon sequestration, storing up to four times more carbon than terrestrial forests, making them crucial allies in the fight against climate change.

Current estimates suggest that only about 86,000 hectares of healthy mangroves remain, emphasizing the urgent need for conservation efforts focused on restoring river flow to the delta.

Migratory Bird Pathways: Rest Stops on Global Journeys

Strategically positioned along the Central Asian Flyway, Pakistan’s rivers and wetlands serve as critical stopover sites for over 1 million migratory birds annually. Species such as greater flamingos, common cranes, and various species of geese and ducks rely on these habitats to rest and refuel during their long migrations between breeding and wintering grounds.

These migratory routes not only boost biodiversity but also offer:

- Opportunities for eco-tourism, attracting birdwatchers and researchers.

- Ecological benefits, as birds contribute to seed dispersal and pest control across landscapes.

Sadly, habitat degradation, wetland shrinkage, and pollution are disrupting these ancient migratory patterns, posing risks to bird populations that have depended on these routes for centuries.

Cultural Heritage and Civilizational Significance

Rivers have long been more than just waterways in Pakistan—they are the threads that weave together history, culture, and human settlement. Flowing through centuries of human experience, these rivers have inspired civilizations, nurtured artistic expression, and shaped the very geography of communities. The story of Pakistan’s rivers is, in many ways, the story of Pakistan itself.

The Cradle of the Indus Valley Civilization: Where History Began

The Indus River is synonymous with one of humanity’s greatest early achievements—the rise of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC). Dating back over 4,500 years, this civilization flourished along the fertile plains carved by the Indus and its tributaries. Cities like Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa, Kot Diji, and Ganeriwala were marvels of their time, showcasing advancements that rivalled their contemporaries in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

What made this civilization extraordinary was its relationship with rivers:

- The grid-pattern urban planning of cities incorporated advanced drainage and water management systems, demonstrating a deep understanding of hydrology.

- Agriculture thrived due to predictable river flooding, which enriched the soil—a system similar to that of the Nile in Egypt.

- Rivers acted as arteries of trade, connecting settlements and facilitating commerce with distant regions, including Central Asia and the Persian Gulf.

Archaeological evidence suggests that these river-fed societies enjoyed a high standard of living, with public baths, granaries, and marketplaces—all sustained by the steady flow of the Indus.

However, the eventual decline of the IVC is also tied to shifting river patterns and climate change, underscoring how critical rivers were—and still are—to human survival and prosperity.

Rivers in Folklore and Traditions: The Soul of Cultural Expression

Throughout history, rivers in Pakistan have transcended their physical presence to become powerful symbols in the nation’s cultural and spiritual life. In Sufi poetry, rivers often represent the eternal flow of divine love or the journey of the soul seeking union with the Creator. Poets like Bulleh Shah, Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, and Sachal Sarmast used rivers as metaphors to explore themes of love, separation, and spiritual awakening.

Culturally, rivers are intertwined with:

- Religious practices across faiths, where rivers are considered purifying forces. Ceremonial baths, offerings, and prayers by riversides are common in many communities.

- Local festivals that celebrate the life-giving power of rivers, especially during planting and harvesting seasons.

- Folklore and oral traditions, where stories of river spirits, mythical creatures, and legendary crossings are passed down through generations.

Artists, musicians, and storytellers continue to draw inspiration from rivers, viewing them as timeless witnesses to human joy, sorrow, and resilience.

Modern Settlements and Urban Growth: Cities Born by the Water

The influence of rivers on settlement patterns did not end with ancient civilizations. Even in modern times, rivers dictated where towns grew into cities and how trade routes evolved. Access to fresh water, fertile land, and navigable paths made rivers natural hubs for commerce and culture.

Some prominent examples include:

- Lahore: While now a sprawling metropolis, Lahore’s origins are closely linked to the Ravi River, which provided sustenance and connectivity, helping it emerge as a center of art, learning, and trade during the Mughal era.

- Multan: Known as the “City of Saints,” Multan’s prosperity was fueled by its position on the Chenab River, making it a vital trading post and spiritual center.

- Sukkur: Strategically located on the Indus River, Sukkur became a key commercial hub, especially after the construction of the Sukkur Barrage in 1932, which revolutionized irrigation and agriculture in Sindh.

These rivers offered:

- Consistent water supplies critical for both drinking and irrigation.

- Trade routes, enabling the movement of goods like textiles, spices, and handicrafts.

- Natural defenses, where rivers acted as protective barriers against invasions in ancient and medieval times.

Today, rivers continue to shape urban landscapes—impacting infrastructure development, influencing cultural spaces like riverfront parks and festivals, and providing economic opportunities through industries such as fishing, tourism, and transport.

Also See: Marine Life in Pakistan

Environmental Threats Facing Pakistan’s Rivers

Picture by: https://hilal.gov.pk/

Once the lifeblood of Pakistan’s civilization and ecology, rivers are now under siege from a combination of human-induced pressures and climate-driven transformations. These waterways, which have sustained life for thousands of years, are rapidly deteriorating due to mismanagement, exploitation, and environmental neglect. The consequences are far-reaching — threatening food security, biodiversity, public health, and the socio-economic stability of millions.

Water Diversion and Damming: Strangling the Natural Flow

While dams and canals have been pivotal in transforming Pakistan into an agricultural powerhouse, the unchecked diversion of river water has come at a grave ecological cost. The construction of major infrastructures like Tarbela, Mangla, and numerous barrages under the Indus Basin Irrigation System has significantly altered the natural flow regime of rivers.

A critical victim of this disruption is the Indus Delta, which has shrunk dramatically over the past decades. Historically nourished by 180 billion cubic meters (BCM) of freshwater annually, current flows have dropped to less than 10 BCM in some years. This drastic reduction has led to:

- Severe delta erosion, with estimates suggesting that Pakistan loses 5,000 acres of delta land annually to the sea.

- Increased saline intrusion, where seawater penetrates up to 100 kilometers inland, devastating fertile agricultural lands and contaminating freshwater supplies.

Furthermore, these diversions have fragmented aquatic habitats, disrupted fish migration routes, and reduced sediment transport, which is vital for maintaining riverine and coastal ecosystems.

Pollution Crisis: Rivers Turned into Toxic Channels

Pollution poses one of the most immediate and visible threats to Pakistan’s rivers. Rapid urbanization and industrial growth, coupled with weak regulatory enforcement, have turned many rivers into dumping grounds for waste.

According to environmental studies:

- Over 90% of Pakistan’s industrial effluents are discharged untreated into rivers.

- Approximately 2 million tons of sewage flows into the Indus River system every year.

Key pollutants include:

- Industrial effluents containing hazardous chemicals, dyes, and heavy metals, particularly from tanneries, textile mills, and chemical plants.

- Agricultural runoff, rich in nitrates and phosphates, leading to eutrophication and oxygen depletion in water bodies.

- Domestic sewage, often laced with pathogens, contributing to waterborne diseases.

The Ravi River is now classified as one of the most polluted rivers in South Asia, while the Lyari River has lost all ecological function, serving solely as a wastewater conduit through Karachi.

This toxic mix has decimated aquatic life, rendered water unfit for human use, and heightened public health crises, especially in marginalized communities dependent on river water for daily needs.

Climate Change Effects: An Unpredictable Future

Pakistan ranks among the top 10 countries most vulnerable to climate change, and its rivers are at the forefront of this battle. The country’s heavy reliance on glacial-fed rivers makes it particularly susceptible to rising temperatures and shifting weather patterns.

Key climate threats include:

- Accelerated glacial melt, which has increased river discharge in the short term but poses a long-term risk of permanent water shortages as glaciers retreat.

- Erratic monsoon behavior, with some regions experiencing catastrophic floods — like the 2010 super floods that displaced millions — while others face prolonged droughts.

- A surge in Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs), with over 3,000 glacial lakes now identified in northern Pakistan, 33 of which are prone to sudden, destructive flooding.

These changes not only imperil human settlements, infrastructure, and agriculture but also disrupt the finely tuned ecological cycles that riverine species depend upon.

Loss of Biodiversity: Silent Extinction Along the Banks

The ecological degradation of rivers is triggering a biodiversity crisis. As habitats shrink and water quality deteriorates, species that once thrived in Pakistan’s rivers and wetlands are now facing extinction.

The most alarming indicators include:

- A sharp decline in fish populations, threatening food security for riverine communities and undermining local economies.

- The endangered Indus River Dolphin, whose population has fragmented into isolated sub-populations due to dams and barrages, making them more vulnerable to extinction.

- Wetlands, critical for migratory birds, are drying up or becoming too polluted to support life, disrupting ancient migratory routes and reducing avian diversity.

This biodiversity loss is a cascading threat—it destabilizes ecosystems, reduces natural resilience against floods and droughts, and strips communities of cultural and economic resources tied to riverine life.

Strategies for Conservation and Sustainable River Management

As Pakistan’s rivers edge closer to ecological collapse, the call for sustainable river management is no longer optional—it’s a necessity for national survival. These rivers not only sustain agriculture and biodiversity but also underpin water security, energy production, and climate resilience. Addressing the crisis demands a multi-faceted strategy that blends policy reform, technological innovation, community action, and cross-border cooperation.

Integrated River Basin Management (IRBM): A Holistic Approach

Traditional river management in Pakistan has often been sectoral and fragmented, focusing on short-term economic gains without considering long-term ecological consequences. This is where Integrated River Basin Management (IRBM) becomes critical. IRBM emphasizes managing rivers as part of a broader ecosystem where land use, water allocation, biodiversity, and human needs are all interconnected.

Key principles of IRBM include:

- Coordinated planning across sectors—agriculture, energy, urban development, and environment.

- Stakeholder engagement, ensuring that local communities, provincial governments, and private sectors are all part of decision-making.

- Managing upstream-downstream dynamics to prevent ecological damage beyond immediate areas of intervention.

Countries like Australia (Murray-Darling Basin) and the Netherlands (Rhine River restoration) have demonstrated how IRBM can reverse decades of degradation. For Pakistan, adopting a similar framework for the Indus Basin could ensure sustainable water use while restoring ecological balance.

Reviving Environmental Flows: Letting Rivers Breathe

One of the most overlooked aspects of river health is the need to maintain environmental flows—the volume of water necessary to keep ecosystems functioning. In Pakistan, excessive diversion for irrigation and industrial use has left long stretches of rivers, especially downstream of major barrages, running dry during critical periods.

To revive these flows, Pakistan must:

- Implement binding legal mandates for minimum flow levels, particularly to sustain the Indus Delta and associated wetlands.

- Reassess water-sharing agreements not only between provinces (under the 1991 Water Apportionment Accord) but also in the context of evolving climate realities.

- Encourage water-efficient agricultural practices to reduce the burden on river systems, such as transitioning from water-intensive crops like rice and sugarcane in arid zones.

Restoring environmental flows would rejuvenate aquatic habitats, curb saline intrusion, and stabilize riverine biodiversity.

Community-Led Initiatives: Empowering the Guardians of Rivers

While top-down policies are essential, real change often begins at the grassroots. Across Pakistan, local communities and NGOs have been instrumental in advocating for cleaner, healthier rivers.

Examples of impactful initiatives include:

- The “Clean Ravi Project”, aimed at reducing industrial discharge and promoting awareness about water pollution in Lahore.

- Community-driven efforts in Sindh to replant mangroves along the Indus Delta, restoring vital coastal ecosystems.

- Educational campaigns in schools and villages promoting the reduction of plastic waste and sustainable water use.

These initiatives highlight that when communities are informed and empowered, they become effective stewards of their natural resources. Expanding such programs nationwide could foster a culture of conservation that complements government action.

Technological and Scientific Interventions: Data-Driven Conservation

In the age of digital transformation, technology offers Pakistan an unprecedented opportunity to monitor, predict, and manage river health proactively.

Key technological strategies include:

- Satellite remote sensing to monitor river morphology, illegal encroachments, and sediment flow patterns.

- Deployment of IoT-based water quality sensors in critical stretches to provide real-time alerts on pollution spikes.

- Advanced GIS mapping tools for planning flood defenses, identifying vulnerable ecosystems, and optimizing water resource allocation.

Institutions like SUPARCO and research bodies under Pakistan’s Ministry of Climate Change are already generating valuable data. However, integrating this data into actionable policy frameworks remains a gap that needs urgent attention.

International Cooperation: Managing Shared Waters Responsibly

With many rivers originating from neighboring countries, Pakistan’s water security is deeply intertwined with regional geopolitics. The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) of 1960, brokered by the World Bank, has been a cornerstone of transboundary water management between Pakistan and India. However, emerging challenges like climate change, increased water demand, and new hydropower projects upstream necessitate a modernized dialogue.

Key areas for diplomatic focus:

- Expanding water-sharing discussions to include Afghanistan, as developments on the Kabul River could impact flows into Pakistan.

- Joint climate resilience programs with China, given the glacial origins of key tributaries in the Tibetan Plateau.

- Participation in global platforms like the UN Watercourses Convention, fostering cooperation over shared water resources and dispute resolution.

Without proactive international engagement, unilateral actions upstream could exacerbate water scarcity and environmental degradation downstream, further destabilizing Pakistan’s vulnerable river ecosystems.

Listen to the Podcast

Resources

-

Pakistan Journal of Botany

“Impact of River Systems on Pakistan’s Agriculture and Ecology”

https://www.pakbs.org/pjbot/papers/1524563266.pdf -

ScienceDirect

“Environmental Flow Requirements and River Basin Management in South Asia”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352485516301074 -

Scientific Research Publishing (SCIRP)

“Assessment of Wetland Ecosystems Linked to River Systems in Pakistan”

https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=70053 -

Marine Ecology Progress Series

“Biodiversity and Ecological Functions of River Deltas”

https://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v157/p1-12/ -

Journal of Environmental Professionals Sri Lanka

“Pollution and Water Quality Challenges in South Asian Rivers”

https://jepsl.sljol.info/articles/10.4038/jepsl.v3i1.7310?_rsc=170px -

ProQuest Open Access

“Climate Change Impacts on Glacial-Fed River Systems in Pakistan”

https://search.proquest.com/openview/3e8669c4a09ce8945777ef2cb1eb93bb/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2027417 -

Pakistan Engineering Congress

“Wetlands in Pakistan: Current Status and Conservation Needs”

http://pecongress.org.pk/images/upload/books/Wetlands%20in%20Pakistan%20What%20is%20Happening%20to%20Them%20(5).pdf -

Frontiers in Environmental Science

“Sustainable Water Management Strategies for Pakistan”

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1113482/full -

Google Books

“The Role of Rivers in Shaping Pakistan’s Ecosystem and Civilization”

https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=S0NEAAAAYAAJ&q=role+of+rivers+in+pakistan+ecosystem