A Ban Long Overdue

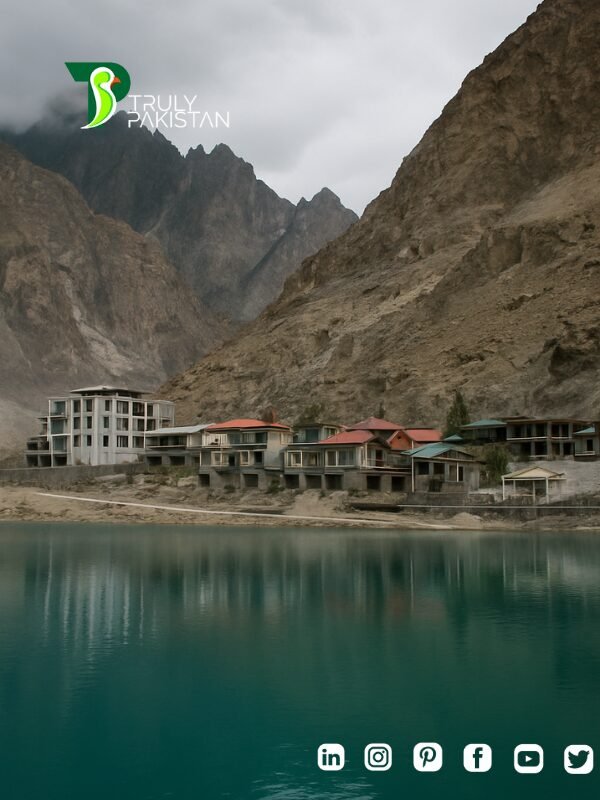

In the heart of Gilgit-Baltistan, Hunza’s serene lakes—once isolated gems of natural beauty—are now shadowed by a rising skyline of cement, glass, and steel. What began as a trickle of eco-curious travelers has turned into an overwhelming wave of mass tourism, transforming these delicate ecosystems into bustling commercial zones. From Attabad’s turquoise waters to the quiet charm of Borit and Duiker, the very landscapes that drew people in are now being reshaped under the weight of unchecked development.

In response to this alarming trend, the GB government recently imposed a construction ban near Hunza lakes, halting new hotel projects and commercial expansion around these critical natural landmarks. While some view the decision as an economic setback, it is, in truth, a much-needed course correction.

This article argues that the GB construction ban near Hunza lakes is not just justified—it is essential. It represents a crucial step toward preserving the ecological integrity, cultural authenticity, and long-term tourism viability of Gilgit-Baltistan. If not now, when?

The Rise of Unsustainable Tourism in Hunza

Tourism in Hunza has witnessed exponential growth over the past decade, especially after the creation of Attabad Lake in 2010—a tragic landslide that turned into a scenic wonder. Social media accelerated the region’s exposure, transforming Hunza from a quiet mountain retreat into a bucket-list destination for both domestic and international travelers. But the speed of this rise came with a heavy cost.

Hotels, cafes, and guesthouses mushroomed along lakefronts and hilltops, often without environmental oversight or urban planning. Entire slopes were leveled to make way for construction. In many areas, sewage systems remain nonexistent or poorly managed, leading to water pollution in lakes that once served as vital natural reservoirs.

Plastic waste, noise pollution, and over-tourism have disrupted wildlife patterns, degraded hiking trails, and overwhelmed local infrastructure. Communities that once thrived on harmony with nature now find themselves struggling to balance economic gains with the cost of environmental degradation.

Hunza, once a symbol of sustainable mountain life, risks becoming a cautionary tale. Without intervention, the same forces that built its tourism boom could end up dismantling the very environment that sustains it.

Also See: Read About the Qatari Princess as Pakistan’s Tourism Ambassador

What the Ban Actually Means

The GB construction ban near Hunza lakes, announced earlier this month, is more than just a regulatory formality—it’s a significant environmental intervention. Under this directive, the Gilgit-Baltistan government has placed a moratorium on all new construction activities, including hotels, guest houses, and other commercial enterprises around the peripheries of Attabad, Borit, and Duiker lakes.

This move comes amid growing concern over the environmental degradation in these sensitive zones. According to the Secretary for Tourism and Law, the aim is to curb the encroachment of commercial activity into protected natural areas and prevent further erosion of the region’s ecological balance. No new permits will be issued, and previously approved but unstarted projects are now under review.

The decision directly impacts real estate developers, hotel investors, and small-scale entrepreneurs who were hoping to capitalize on the lakes’ growing popularity. For the local communities, this brings a mixed bag of reactions—while some see it as a threat to livelihoods, others welcome it as a long-overdue effort to reclaim the natural identity of the region.

More importantly, the ban signals a shift in governance thinking—from reactive development to proactive preservation. It sends a message that tourism in Gilgit-Baltistan cannot grow at the expense of its lakes, land, and legacy.

Why This Ban Is a Step in the Right Direction

At first glance, the GB construction ban near Hunza lakes may seem like a blow to tourism investment, but it is in fact a critical and strategic pause—a recalibration of priorities. Preserving the integrity of natural landscapes like Attabad, Borit, and Duiker is not an anti-tourism measure. It’s a decision rooted in long-term sustainability and respect for the environment that sustains both life and livelihood in the region.

Unchecked construction poses serious threats to the lakes’ fragile ecosystems. The runoff from construction sites, the pressure on waste management systems, and the permanent alteration of natural contours all degrade the quality of the environment. If left unchecked, Hunza’s lakes risk becoming polluted, overcrowded, and ultimately undesirable as travel destinations—driving tourists away instead of attracting them.

The ban also reinforces the idea that not all development is progress. Gilgit-Baltistan doesn’t need more concrete to succeed—it needs a smarter tourism model that values conservation over commodification. By halting construction, the government is buying time to reassess policies, implement better zoning regulations, and plan for eco-conscious growth that serves both visitors and residents.

In the broader context, this move can serve as a benchmark for other vulnerable tourist spots across Pakistan. It reflects a growing recognition that environmental protection is not a hurdle to economic development but a prerequisite for it.

Counter-Arguments: Local Economy vs. Conservation

Despite its ecological merit, the GB construction ban near Hunza lakes has drawn criticism—particularly from those whose livelihoods depend on the region’s booming tourism sector. For many small business owners, tour operators, and hotel workers, the ban feels like a sudden stop in the middle of peak travel season. In areas where economic opportunities are scarce, tourism is not just a seasonal activity, it’s a lifeline.

Some argue that halting construction without offering alternatives risks alienating the very communities that have long been custodians of this landscape. When decisions are made without meaningful local consultation or economic support mechanisms, they are likely to be met with resistance, skepticism, or even non-compliance.

Critics also point to the lack of enforcement in the past. Similar restrictions have been announced before, only to be undermined by influential investors or unclear zoning boundaries. If this ban follows the same pattern—poorly implemented and selectively enforced—it will not only fail to protect Hunza’s lakes, but also deepen mistrust between local communities and government authorities.

These concerns are valid. Conservation cannot succeed in a vacuum. It must be accompanied by investment in sustainable alternatives—like eco-tourism training, microloans for green businesses, and incentives for locals to participate in responsible tourism models. A ban alone is not a solution. It is only the first step.

A Better Tourism Model for GB

If the GB construction ban near Hunza lakes is the first step, then the next must be a visionary shift in how we approach tourism in Gilgit-Baltistan. The future of travel in the region cannot be built on unchecked construction and short-term profits. It must rest on a foundation of sustainability, inclusivity, and resilience.

A better tourism model begins with community-based tourism, where local residents—not outside investors—take the lead in shaping how tourism is experienced and managed. Small-scale, family-run eco-lodges, trekking services, and cultural homestays can offer authentic visitor experiences without burdening natural resources.

International examples offer valuable lessons. In Bhutan, tourism is carefully controlled through a high-value, low-impact strategy. In Costa Rica, protected forests generate more revenue through conservation-based tourism than logging ever could. Pakistan too has models to learn from—initiatives in Swat and Skardu have demonstrated that sustainable planning, when backed by strong policy and community participation, can yield positive results.

Technology and innovation can also play a role. Digital visitor permits, waste monitoring systems, and environmental awareness campaigns can ensure accountability and education among tourists. Coupled with zoning laws, capacity limits, and environmental audits, these tools can help preserve the beauty of Hunza’s lakes while still welcoming the world to see them.

Tourism in Gilgit-Baltistan should not be about quantity, but quality. It should not only aim to bring people in, but also leave nature unharmed—and even improved—by their presence.

What Needs to Happen Next

The GB construction ban near Hunza lakes opens an important window of opportunity—but only if followed by smart, inclusive, and decisive action. A ban without a blueprint is simply delay. What’s needed now is a comprehensive plan that protects the environment while empowering local communities to be co-stewards of the region’s future.

First, Gilgit-Baltistan needs clear zoning regulations that designate protected environmental zones, tourism corridors, and permissible construction areas. These must be informed by environmental impact assessments and updated regularly in response to ecological shifts.

Second, the government must launch community consultation forums. Local voices—especially those of indigenous communities, small business owners, and youth—must be part of the policy-making process. A top-down approach will not work in places where trust in governance has historically been fragile.

Third, tourism operators and investors should be encouraged—through grants, training, and tax incentives—to transition toward eco-friendly infrastructure. Solar-powered guesthouses, composting toilets, and local supply chains can reduce environmental footprints while creating jobs.

Fourth, visitor education campaigns must become standard practice. Signage, digital guides, and travel SOPs should clearly inform tourists about permissible behaviors around lakes and protected areas. Tourism is a two-way exchange, and visitors must take responsibility for their impact.

Lastly, the success of this ban must be monitored transparently, with progress reports, penalties for violations, and measurable conservation benchmarks. Accountability is the only way to ensure that this promising step becomes lasting policy.

A Ban Is Not a Block – It’s a Beginning

The GB construction ban near Hunza lakes is not an end to progress—it is the beginning of a more thoughtful, sustainable, and equitable future for tourism in Gilgit-Baltistan. It challenges us to rethink what development truly means. Is it more concrete and hotels, or cleaner air, protected landscapes, and empowered communities?

For too long, the pursuit of tourism revenue has overlooked the fragile ecological balance of places like Attabad, Borit, and Duiker. But the cost of overdevelopment is now too visible to ignore. This ban offers a chance to pause, reflect, and course-correct before irreversible damage is done.

Let us not treat this as an obstacle, but as an opening. An opportunity to build a tourism model that does not sacrifice nature for numbers, that does not leave communities behind, and that honors the awe-inspiring beauty of Hunza for generations to come.

In protecting our lakes, we are not just preserving water or landscape—we are preserving identity, culture, and the soul of a region. The ban, if supported with vision and action, can become a turning point in how Pakistan approaches tourism. Let’s not waste it.

Reference:

Dawn News Article – “Construction activities banned near lakes in Hunza”:

🔗 https://www.dawn.com/news/1924157

One thought on “Why the GB Construction Ban Matters”