Where Threads Meet History

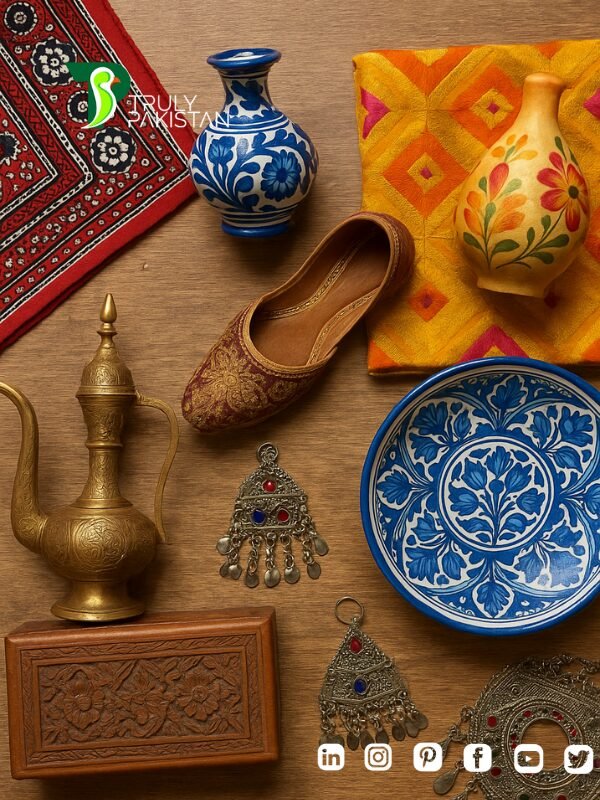

When you hold a piece of handcrafted Ajrak or admire the intricate embroidery on a Phulkari shawl, you’re not just looking at a product—you’re witnessing a story passed down through generations. In Pakistan, handicrafts are more than ornamental souvenirs. They are cultural legacies that speak of identity, heritage, and the enduring spirit of skilled artisans across the region.

With a history that stretches back over 5,000 years, from the Indus Valley Civilization to the artistic refinement of the Mughal era, Pakistan’s handicraft traditions have stood the test of time. Each region boasts its own unique style—whether it’s the deep indigo of Sindh’s Ajrak, the glowing blue pottery of Multan, or the wood carvings of Peshawar—each piece tells a story rooted in land, people, and purpose.

This blog explores the vast world of handicrafts of Pakistan, taking you on a regional journey through the colors, textures, and traditions that define the country’s artistic soul.

The Legacy of Handicrafts in Pakistan

The story of handicrafts in Pakistan begins long before the country itself was formed. Traces of artisanal traditions date back over five millennia, with archaeological finds from Mohenjo-daro and Harappa revealing early examples of pottery, textile impressions, and beadwork. These ancient objects weren’t merely utilitarian—they reflected a thriving artistic culture where design and function went hand in hand.

As civilizations evolved, so did the crafts. The Gandhara period introduced Greco-Buddhist influences, which are visible in stone carving and sculpture. Later, the Mughal Empire elevated arts and crafts to new heights, introducing techniques in tile work, miniature painting, and textile weaving that continue to inspire artisans to this day.

Colonial rule brought both disruption and innovation. While industrialization threatened traditional methods, it also created new markets for Pakistani crafts in Europe and beyond. Chiniot’s furniture, Lahore’s tile mosaics, and Sindh’s embroidered fabrics gained commercial recognition, marking the start of handicrafts as export commodities.

In rural communities, these crafts were (and still are) part of daily life and cultural rituals. A girl’s dowry might include hand-stitched rilli quilts, embroidered shawls, or handwoven rugs—each piece a reflection of her heritage and her family’s values. In many regions, craftsmanship is passed through generations, often taught by mothers and grandmothers in the intimacy of home workshops.

Today, the handicrafts of Pakistan serve as a living connection between past and present. They are expressions of both regional identity and national pride—art forms that have endured through time, turmoil, and transformation.

Regional Handicrafts of Pakistan

A. Sindh – The Soul of Color and Pattern

Sindh is perhaps the most instantly recognizable region when it comes to traditional handicrafts in Pakistan. With its bold use of color, geometric precision, and deeply symbolic motifs, Sindhi craftsmanship reflects the province’s ancient heritage and vibrant cultural identity.

Ajrak – The Symbol of Sindhi Pride

Ajrak is more than a piece of fabric—it’s a cultural emblem. Traditionally made using a complex block-printing technique with natural dyes like indigo and madder, Ajrak designs are symmetrical and rooted in Islamic geometry. Its production involves multiple stages of dyeing, washing, and drying, sometimes taking weeks to complete. Worn during weddings, festivals, and funerals, Ajrak is deeply embedded in the social fabric of Sindhi life.

-

Origin: Traces back to the Indus Valley Civilization (around 2500 BCE)

-

Production hubs: Hala, Bhit Shah, and Khairpur

-

Cultural use: Worn by men and women, also used as décor or a mark of hospitality

Sindhi Embroidery – A Language in Threads

Known for its mirror work, vibrant thread colors, and symbolic motifs, Sindhi embroidery is done on clothes, wall hangings, and even household accessories. Each design can indicate a woman’s social status, community, or even marital status. Patterns include peacocks, flowers, and stylized paisleys—all stitched freehand, often with no formal template.

-

Techniques used: Satin stitch, chain stitch, mirror work

-

Artisan base: Largely done by women in rural households

-

Contemporary relevance: Increasingly featured in modern fashion and home décor

Rilli Quilts – Patchwork Heritage

Made by stitching together vibrant scraps of fabric, rilli quilts are a form of folk art that is as functional as it is beautiful. Each quilt is unique, often telling personal stories through color and pattern. Traditionally prepared as part of a dowry, rillis are also used in everyday life for bedding and floor mats.

-

Designs: Abstract geometry, floral motifs, or tribal patterns

-

Symbolism: Often considered a woman’s way of documenting memory and creativity

-

Modern use: Now sold as decorative throws or wall art globally

Hala Pottery – Earth, Fire & Art

Hala, a town steeped in Sufi heritage, is also known for its unique style of glazed pottery. Influenced by Persian and Central Asian styles, Hala pottery features vibrant glazes in blue, green, and white, often with floral or calligraphic designs.

-

Product types: Vases, plates, tiles, urns

-

Aesthetic: Combines Islamic art elements with local storytelling

-

Export status: Highly regarded in international craft exhibitions

Sindh’s handicrafts are a testament to centuries-old techniques, spiritual symbolism, and communal knowledge. Despite modern challenges, these crafts continue to thrive, thanks to dedicated artisans and growing interest from global consumers, tourism markets, and digital platforms.

Punjab – Threads of Tradition and Craft

Punjab, the land of five rivers, has long been a cultural and artistic hub. Its handicrafts reflect the region’s agricultural richness, festive spirit, and centuries of interaction with diverse civilizations—from ancient invaders to the Mughal and British empires. Punjabi crafts combine elegance with utility, blending everyday practicality with extraordinary detail.

Phulkari – Embroidered Expressions of Love

The word Phulkari means “flower work,” and this art form lives up to its name. Phulkari is an embroidery style where intricate floral and geometric patterns are hand-stitched using vibrant threads on coarse cotton or khaddar fabric. Traditionally, women created phulkaris for weddings, rituals, and celebrations—often as part of their bridal trousseau.

-

Technique: Darning stitch from the reverse side using silk floss thread

-

Designs: Bagh (dense), Chope (bridal), Til Pat (minimal)

-

Symbolism: Each motif tells a story—fertility, happiness, prosperity

-

Modern revival: Popular in fashion, jackets, bags, and scarves

Khussa – Embellished Footwear with Royal Roots

Handcrafted with leather and elaborately embroidered with beads, threads, sequins, or mirrors, khussa shoes are a staple of Punjabi tradition. Once worn by royals, they’re now a vibrant accessory for weddings and festivals.

-

Origin hubs: Multan, Lahore, and Bahawalpur

-

Styles: Men’s khussas are often plain with minimal stitching, while women’s khussas are more decorative

-

Making process: Entirely handmade—cutting, stitching, and embellishing done by skilled artisans

Chinioti Furniture – Carving Dreams in Wood

Chiniot, a small town in Punjab, is globally renowned for its hand-carved furniture. Craftsmen here use sheesham (rosewood) to carve floral, Mughal, and Islamic patterns into beds, tables, cupboards, and even mosque interiors.

-

Material: Solid wood (mainly rosewood), brass, and inlay work

-

Motifs: Islamic arches, floral vines, paisleys

-

Recognition: Exported globally as luxury furniture

Tile Work & Inlay Art – Echoes of the Mughals

Influenced by Lahore’s grand Mughal architecture, artisans across Punjab create stunning tile mosaics and bone inlay décor pieces. These are used in home decoration, furniture, and giftware.

-

Applications: Table tops, wall tiles, mirror frames, lamp bases

-

Color palette: Blues, greens, golds—Mughal-inspired tones

-

Notable regions: Lahore, Gujrat, and Multan

Punjab’s handicrafts aren’t just about aesthetics—they’re heirlooms of emotion, function, and artistry. From the elegance of phulkari to the royal flair of khussa and the precision of woodwork, Punjab’s art forms continue to evolve while staying rooted in age-old traditions.

Multan – City of Saints, Soil, and Skill

Multan, one of the oldest cities in South Asia, is a spiritual and artistic center. Known as the “City of Saints,” it is equally famous for its deeply rooted artisanal culture. Its crafts draw from Islamic, Persian, and local influences, translating centuries of devotion, mysticism, and creativity into tangible works of art.

Multani Blue Pottery – A Fusion of Earth and Sky

This iconic craft is the soul of Multani artistry. Multani Blue Pottery is celebrated for its rich cobalt blue, turquoise, and white hues, often seen on plates, tiles, and vases. The designs usually feature Islamic calligraphy, floral vines, and symmetrical patterns, executed through a Persian-inspired glazing technique.

-

Technique: Hand-molded clay → sun-dried → white base glaze → hand-painted → kiln-fired

-

Design influence: Persian, Kashmiri, and Mughal aesthetics

-

Applications: Wall tiles, bowls, lamps, vases, urns

-

Artisan base: Primarily family-run workshops in the old city

Camel Skin Lamps – Light with a Local Soul

A rare craft unique to Multan, these translucent lamps are made by shaping and painting dried camel skin into vibrant patterns. When lit, they emit a warm glow, highlighting hand-painted floral, geometric, or Sufi-inspired artwork.

-

Crafting process: Skin is cleaned, molded on a mold, dried, then painted using natural dyes

-

Designs: Often carry symbols of Multan’s shrines and spiritual culture

-

Use: Popular in home décor, festivals, and souvenir exports

Tile Work & Glazed Ceramics – Echoes of Shrines

The shrines of Bahauddin Zakariya and Shah Rukn-e-Alam are covered in mosaic tile work, a signature Multani craft. Artisans create glazed tiles with calligraphic inscriptions and nature motifs that mirror the aesthetic of Sufi architecture.

-

Color palette: Dominantly blue, green, white, and yellow

-

Application: Modern adaptations include tabletop tiles, garden planters, wall murals

-

Heritage tie: Used extensively in shrine architecture and cityscape restoration

Khussa Shoemaking – Soulful Steps

Multan also contributes to Punjab’s khussa legacy, offering vibrantly embellished footwear with floral beadwork, zari threads, and miniature mirrors. These handcrafted shoes are a symbol of ethnic pride and are often paired with traditional attire.

-

Process: Fully handmade by shoemaking families

-

Specialty: Festive and bridal collections with intricate detailing

-

Export value: High demand in South Asia and Middle Eastern craft markets

Multan’s handicrafts are more than beautiful—they are a reflection of its Sufi philosophy, reverence for tradition, and unmatched earth-to-art transformation. In every piece of glazed pottery or camel-lamp glow, you’ll find a part of Multan’s spiritual soul.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) – The Art of Mountains and Metal

The crafts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are born from the rugged beauty of the north—where mountains tower, traditions run deep, and resilience is woven into every thread and carving. Whether it’s the historic bazaars of Peshawar or the alpine valleys of Chitral, this region is a haven for heritage-rich handicrafts shaped by both tribal culture and centuries of trade through the Silk Route.

Peshawar Wood Carving – Stories Etched in Timber

Peshawar is famous for its wood carving, a legacy that spans centuries. Craftsmen, using basic tools and exceptional precision, create ornate patterns on doors, furniture, window frames, and ceilings. The floral and geometric designs often reflect Islamic aesthetics, particularly those seen in old mosques and havelis.

-

Materials used: Deodar, walnut, and sheesham (rosewood)

-

Motifs: Arches, rosettes, floral vines, and latticework (jharoka)

-

Notable products: Chests, cupboards, wall panels, prayer niches

-

Cultural relevance: Used in both religious and residential architecture

Brass & Copper Crafts – Shining Echoes of the Past

Metalworking in KP, particularly in Peshawar, Mardan, and Kohat, is a legacy of Mughal craftsmanship. Artisans skillfully mold and engrave brass and copper into trays, jugs, hookahs, bowls, and utensils, often with Islamic calligraphy or Persian floral designs.

-

Technique: Hammering, engraving, polishing, and aging

-

Products: Samovars, urns, tea sets, decorative plates

-

Modern use: Popular in rustic interior design and collectors’ items

-

Economic value: Exported across the Gulf and Central Asia

Chitrali Woolen Crafts – Warmth with Identity

From the cool valleys of Chitral come crafts woven from pure wool, offering both functionality and cultural identity. The Chitrali cap (Pakol) is the most iconic product—worn by men across KP and Gilgit-Baltistan, symbolizing regional pride.

-

Pakol cap: Made of hand-spun wool, rolled and shaped by hand

-

Other items: Hand-woven shawls, mufflers, socks, and rugs

-

Patterns: Tribal motifs and natural dyes

-

Cultural significance: Often gifted in ceremonies or worn during national events

Tribal Jewelry – Metal as Memory

The tribal communities of KP and the former FATA regions craft bold, silver-based jewelry that reflects ethnic traditions and symbolic storytelling. These pieces are both decorative and talismanic.

-

Designs: Heavy cuffs, large earrings, beaded necklaces, anklets

-

Symbolism: Protection, fertility, status, and storytelling

-

Materials: Silver, semi-precious stones, beads, glass

-

Target markets: Highly sought in cultural exhibitions and museums

From hand-carved wooden panels to silver jewelry worn with pride, KP’s handicrafts are as resilient and bold as the mountains that surround them. Rooted in tribal legacy and influenced by centuries of history, these crafts remain a testament to the region’s enduring artistry and cultural identity.

Balochistan & the Northern Areas – Rugged Roots and Raw Beauty

Balochistan and the northern territories of Pakistan—comprising Gilgit-Baltistan, Hunza, and Skardu—offer a treasure trove of handicrafts shaped by rugged landscapes, nomadic traditions, and centuries of self-sufficiency. Isolated by geography but rich in culture, these regions preserve artistic expressions that are as raw as they are refined.

Balochi Embroidery – Threads of Identity

Balochi embroidery is bold, geometric, and painstakingly detailed—usually stitched onto dresses, shawls, and accessories. The patterns vary by tribe and region, often acting as cultural markers for origin and social status. Unlike the floral elegance of Punjab, Balochi embroidery is sharp and angular, often done in vibrant reds, blacks, and golds.

-

Techniques: Hand embroidery using silk threads and mirror work

-

Used on: Women’s dresses (Phashk), men’s kurtas, household textiles

-

Symbolism: Patterns often represent nature, protection, or tribal lineage

-

Economic role: Vital for income in rural Baloch communities

Rug & Kilim Weaving – Patterns from Nomadic Memory

Handwoven rugs and kilims from Balochistan, Hunza, and Gilgit-Baltistan are known for their minimalist beauty and durability. These flat-woven textiles are made using wool dyed with natural pigments, sourced from herbs, roots, and stones. Patterns often mirror the life of the weaver: mountains, animals, symbols of harmony and protection.

-

Materials: Sheep wool, goat hair

-

Designs: Diamond shapes, zig-zags, mountain peaks, and the tree of life

-

Usage: Rugs, prayer mats, wall hangings, and saddle bags

-

Export markets: Europe, the Middle East, and eco-conscious artisan buyers

Woolen Shawls and Mufflers – Softness for Survival

The extreme cold of the northern regions has given rise to an indigenous wool industry, where locally sheared wool is spun, dyed, and woven into shawls, scarves, socks, and hats. These products are not only utilitarian but also deeply aesthetic.

-

Production regions: Hunza, Skardu, Astore

-

Color palette: Earth tones—brown, grey, off-white

-

Modern appeal: Increasingly seen in eco-fashion markets for their sustainability

Stone Craft & Woodwork – Nature as Canvas

Northern artisans carve soapstone, walnut wood, and apricot wood into kitchenware, prayer beads, jewelry boxes, and utensils. The minimalism in their designs is inspired by Buddhist and Islamic traditions—simple, earthy, and functional.

-

Popular items: Salt lamps, bowls, carved frames, spice boxes

-

Notable areas: Gilgit, Hunza, Nagar

-

Sustainability angle: Often made from discarded or repurposed natural materials

Despite being some of the most underrepresented in mainstream craft markets, the artisans of Balochistan and the Northern Areas keep their traditions alive through raw resilience and creativity. Each woven thread and carved stone speaks of self-reliance, heritage, and adaptation—reflecting the soul of regions that have always stood apart, yet deeply connected to Pakistan’s cultural fabric.

Economic and Cultural Importance

The handicrafts of Pakistan are more than just cultural artifacts—they are pillars of rural economies, vehicles for women’s empowerment, and ambassadors of the country’s identity on the global stage. Every embroidered shawl, hand-carved table, or glazed vase carries not just aesthetic value, but also economic opportunity and cultural continuity.

A Backbone for Rural Economies

Across Pakistan, particularly in rural areas, handicrafts are often the main source of livelihood for thousands of families. Women play a vital role—crafting embroidery, rillis, and accessories from home while managing domestic responsibilities. This cottage industry model fosters both economic resilience and social inclusion.

-

Over 80% of handicraft production is done in informal or home-based setups

-

Crafting often provides income in areas with limited access to jobs, especially for women

-

Artisanal skills are usually passed down generationally, preserving family heritage

Women’s Empowerment Through Craftsmanship

Handicrafts provide a dignified and sustainable income channel for women, particularly in Sindh, Punjab, and Balochistan. Beyond financial support, crafting gives women autonomy, social mobility, and respect within their communities.

-

NGOs and social enterprises (like Kaarvan and Indus Heritage Trust) support craftswomen

-

Many female artisans now sell through Instagram, WhatsApp, and online platforms

-

Handicraft training programs have become a bridge to literacy and entrepreneurship

Cultural Diplomacy and Global Exports

From the China International Import Expo to regional cultural fairs in the Middle East and Europe, Pakistani handicrafts are steadily gaining global recognition. Their authenticity, handmade appeal, and eco-friendly processes resonate strongly with international consumers.

-

Multani pottery, khussa shoes, and Kashmiri shawls are exported to the UAE, UK, USA, and Turkey

-

UNESCO and WTO reports list handicrafts as high-potential sectors for developing countries

-

Craft exports promote Pakistan’s soft image and support cultural diplomacy

Preserving Intangible Cultural Heritage

Handicrafts are not just objects—they embody stories, rituals, aesthetics, and philosophies. In a rapidly digitizing world, these crafts preserve traditions that are otherwise at risk of being lost. They help maintain:

-

Cultural identity in diaspora communities

-

Tourism experiences (e.g., visiting artisan villages, handicraft festivals)

-

Inter-generational bonding, where elders pass on techniques to the youth

The economic and cultural significance of Pakistan’s handicrafts lies in their dual identity as living heritage and viable livelihood. They are threads that weave together economy, identity, and creativity—and they continue to stitch new futures for the people behind them.

Challenges to Traditional Crafts

While the handicrafts of Pakistan represent a vibrant cultural legacy and a critical economic resource, they are increasingly under threat from a range of social, economic, and systemic challenges. Without timely intervention, Pakistan risks losing not only the crafts themselves but also the communities, skills, and intangible heritage they embody.

1. The Rise of Machine-Made Replicas

One of the most urgent challenges is the growing presence of mass-produced, machine-made products that imitate traditional Pakistani crafts. These synthetic versions are often sold at much lower prices, flooding local markets and undercutting the livelihoods of genuine artisans.

Crafts like Phulkari, Ajrak, and Rilli are frequently replicated with digital printing or machine embroidery, making them more accessible to price-sensitive consumers. However, these copies lack the cultural depth, labor intensity, and craftsmanship of the originals. Unfortunately, many buyers are unable to distinguish between the two, leading to declining demand for authentic handmade pieces.

Artisans, who rely on manual, time-consuming techniques, simply cannot compete with the speed and scale of machine production, forcing many to abandon their trades or drastically reduce their output.

2. Urbanization and Skill Abandonment

As urbanization accelerates and rural youth migrate to cities for better job prospects, traditional crafts are being left behind—both physically and culturally. Entire villages that once specialized in pottery, woodwork, weaving, or embroidery are witnessing a sharp decline in artisan activity.

The younger generation increasingly views craft-based work as outdated, low-income, or socially undervalued. As a result, families that once passed down artisan skills for generations are now disengaged. Moreover, the physical displacement caused by urban expansion also contributes to the erosion of craft hubs like Chiniot, Hala, and Bahawalpur, where space, raw material access, and community networks are essential to sustaining these traditions.

3. Lack of Institutional and Policy Support

Despite their cultural and export potential, handicrafts in Pakistan suffer from chronic neglect at the policy level. There is no unified government strategy focused on preserving, promoting, or financially supporting artisans.

Most craftspeople operate informally, without access to social security, pension schemes, or health benefits. In addition, rising costs of raw materials and limited access to affordable credit make it difficult for small-scale artisans to sustain their work.

Another critical gap is the lack of Geographical Indications (GI) protections. Without GI tags, regional crafts like Multani Blue Pottery or Sindhi Ajrak are vulnerable to unauthorized commercial use, reducing the brand value of origin-specific artistry.

Artisans also face logistical hurdles in reaching broader markets. Exhibitions, e-commerce platforms, and tourism partnerships often bypass these creators due to digital illiteracy or lack of facilitation.

4. Cultural Disconnect and the Loss of Storytelling

Crafts are not just products—they are living embodiments of cultural memory. However, the oral traditions, stories, and symbols tied to these crafts are gradually being lost. The deeper meanings behind color choices, stitch types, or patterns are rarely documented, and without this context, many modern iterations of traditional crafts become aesthetically hollow.

Few schools or institutions include craft education in their curricula, resulting in generations growing up with little to no knowledge of their artistic heritage. In many artisan households, children are no longer learning the skills of their parents or grandparents, either because of a lack of interest or economic pressure to pursue other careers.

This disconnect leads to a dilution of authenticity. Crafts become commercial items divorced from their cultural roots, weakening their historical and artistic significance.

If these challenges continue unchecked, the consequences will go far beyond economic losses. Pakistan stands to lose entire artisan communities, rich traditions, and the cultural identities that define its diverse regions. Addressing these issues requires not just preservation efforts but revitalization strategies that make crafts relevant, sustainable, and respected in the modern world.

Also See: Traditional Handicrafts of Pakistan

Revival and Preservation Efforts

Despite the mounting challenges facing the handicrafts of Pakistan, there is a growing movement of hope, shaped by passionate individuals, cultural institutions, digital innovators, and public-private collaborations. Together, they are working not only to preserve endangered art forms, but to create sustainable income opportunities for the artisans behind them, many of whom are women, youth, and members of marginalized communities. This revival is not just about the past; it is about crafting a more inclusive and culturally enriched future.

1. The Digital Renaissance: Marketplaces and E-Commerce

Social media and e-commerce have transformed how handicrafts reach audiences. What was once confined to roadside stalls or local bazaars is now accessible to global buyers with a tap or click. Thousands of artisans and small enterprises now use platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp to sell directly to customers, cutting out middlemen and gaining fairer returns.

Online pages such as Reviving Pakistan, Waoo Handicrafts, and the Indus Heritage Network are bringing artisan stories to the forefront, creating direct bridges between rural craftsmanship and urban or international markets. Young craftpreneurs are utilizing visual storytelling, behind-the-scenes reels, and DIY videos to connect with modern consumers who seek authenticity and human connection.

Meanwhile, larger platforms like Daraz, TCS Sentiments Express, and Hunarmand Pakistan are onboarding artisans, providing them with payment gateways, packaging assistance, and marketplace visibility, making traditional products digitally accessible to local and diaspora buyers alike.

2. Skill Development Through NGOs and Government Programs

Institutions such as Kaarvan Crafts Foundation, SMEDA, TEVTA, and the Indus Heritage Trust are playing a critical role in reviving lost skills and modernizing artisan potential. These organizations offer structured training programs in embroidery, stitching, khussa-making, and design thinking, particularly aimed at empowering women and young people.

Beyond basic training, these programs also promote value addition—transforming classic crafts like rilli patchwork into contemporary handbags, or adapting khussa shoes for bridal fashion collections. Such initiatives ensure that crafts remain culturally rooted but economically viable.

In some provinces, government bodies have established craft villages, cultural complexes, and artisan bazaars, encouraging both tourism and localized micro-economies built around heritage.

3. Cultural Showcases and Global Representation

The re-emergence of crafts on national and international stages has fueled a renewed sense of pride among artisans. Events like Lok Virsa Mela in Islamabad, Punjab Cultural Day, and the Sindh Festival serve as powerful platforms for craftspeople to display their work, engage directly with buyers, and preserve cultural narratives.

Pakistan’s presence at global expos—such as the China International Import Expo—has also been significant. Products like Multani blue pottery and Sindhi Ajrak have gained admiration abroad, highlighting the country’s rich artistic potential. Initiatives like TrulyPakistan are taking this further by integrating handicrafts into broader tourism campaigns, positioning crafts as essential experiences rather than just items.

4. Documentation, Research, and Cultural Archiving

A quieter, yet deeply important form of revival lies in research and storytelling. Universities and independent researchers are beginning to document the meanings, histories, and processes behind Pakistan’s crafts. Publications like the Journal of Development and Social Sciences now feature artisan case studies and livelihood reports, offering academic validation and policy insights.

Digital platforms like SlideShare, Pakorococo, and TrulyPakistan.net are curating accessible heritage guides, blogs, and photo essays—preserving narratives that would otherwise disappear with time. These archives serve not just as memory banks but also as design inspiration for architects, fashion designers, and contemporary artists who want to integrate traditional motifs into modern expression.

A Future Woven with Purpose

The revival of Pakistani handicrafts is a testament to the resilience and relevance of traditional arts in a changing world. These efforts are not simply about nostalgia—they represent a dynamic reimagining of heritage, economy, and identity. By combining policy reform, digital innovation, grassroots training, and cultural storytelling, Pakistan can position its artisans as global leaders in sustainable, ethical, and meaningful craftsmanship.

The road ahead requires support from all sectors—government, private enterprises, media, academia, and consumers. Together, we can ensure that the soul of Pakistan’s crafts not only survives but thrives.

Stitching the Past into the Future

The handicrafts of Pakistan are not just aesthetic artifacts—they are living traditions, woven with memory, identity, and resilience. From the mirror-laced embroidery of Sindh to the earthy ceramics of Multan, from the carved walnut of Peshawar to the woven kilims of Hunza, each craft tells a story rooted in history and shaped by hand.

These crafts carry the essence of Pakistan’s diverse regions, each contributing to a collective cultural heritage that deserves celebration and protection. Yet, they also stand at a crossroads—facing industrialization, cultural erosion, and economic neglect. Without sustained efforts, we risk losing not only the techniques but also the communities that have nurtured them for generations.

The good news? A new chapter is already being written. Artisans are going digital. Younger audiences are rediscovering handmade goods. NGOs and cultural institutions are stepping in to train, support, and promote. And platforms like TrulyPakistan are playing a pivotal role in documenting and sharing these stories with the world.

As admirers, tourists, policymakers, or entrepreneurs, we all have a part to play in this revival. By supporting local crafts, telling their stories, and integrating them into the future of design and tourism, we don’t just buy a product—we invest in Pakistan’s artistic soul.

References

-

Multani Blue Art. Handicrafts of Pakistan. Retrieved from: https://multaniblueart.com/handicrafts-of-pakistan/

-

The Reviving Pakistan. Explore Traditional Crafts & Cultural Revival. Retrieved from: https://therevivingpakistan.com/lander

-

Journal of Development and Social Sciences (JDSS). Crafts, Culture & Sustainable Livelihoods in Pakistan. Retrieved from: https://ojs.jdss.org.pk/journal/article/view/1166

-

PakistaniCrafts.com. Handicrafts of Pakistan – Regions and Types. Retrieved from: https://pakistanicrafts.com/handicrafts-of-pakistan/

-

TrulyPakistan.net. Traditional Handicrafts of Pakistan. Retrieved from: https://trulypakistan.net/traditional-handicrafts-of-pakistan/

-

Waoo Handicrafts. 9 Most Amazing Handicrafts of Pakistan. Retrieved from: https://waoohandicrafts.com/9-most-amazing-handicrafts-of-pakistan/

-

Wikipedia. Pakistani Craft. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pakistani_craft

-

SlideShare. Arts and Crafts of Pakistan – Presentation. Retrieved from: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/arts-and-crafts-of-pakistan/74177577

-

The Nation. Peshawar: A Beacon of Traditional Craftsmanship. Retrieved from: https://www.nation.com.pk/13-Jul-2024/peshawar-a-beacon-of-traditional-craftsmanship-in-south-asia

-

Scribd. Handicrafts in Pakistan – Cultural Studies Resource. Retrieved from: https://www.scribd.com/document/443180220/Handicrafts-in-Pakistan