River Tourism in Pakistan – Exploring the Indus Basin

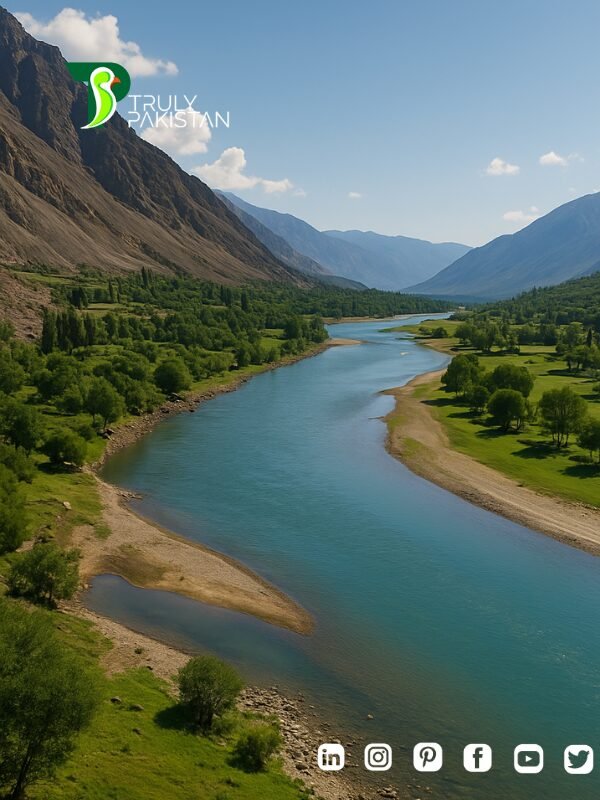

Picture by: https://edubaba.in/the-indus-river-system/

Rivers have long served as lifelines of human civilization, nurturing agriculture, enabling trade, inspiring myths, and giving rise to ancient cities. In Pakistan, these waterways continue to pulse through the land, sustaining one of the world’s most significant river networks: the Indus Basin. While the Indus River and its tributaries form the backbone of the country’s economy and agriculture, their potential as engines of ecotourism remains vastly untapped.

The Indus River System—comprising the mighty Indus and its key tributaries like the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—spans from the glacial highlands of Gilgit-Baltistan to the mangrove-lined delta of Sindh. This network not only irrigates vast agricultural plains but also cradles biodiversity hotspots, heritage sites, and communities with rich cultural traditions. Yet, river-centric tourism remains largely overlooked in national development plans and regional tourism strategies.

As climate change intensifies and rural economies seek sustainable pathways, Pakistan stands at a crucial juncture. River tourism, rooted in ecotourism principles, offers an opportunity to blend conservation with livelihood generation. Whether it’s rafting in the north, birdwatching in central Punjab, or exploring the delta’s mangroves, Pakistan’s rivers could soon become not just sources of water, but destinations in themselves.

Overview of the Indus River System

The Indus River System is one of the most significant and complex river basins in the world, both in its scale and its impact on human life, agriculture, and ecology. Originating from the Tibetan Plateau near Lake Mansarovar, the Indus River flows through the Ladakh region, enters Gilgit-Baltistan, and then traverses the entire length of Pakistan, ultimately draining into the Arabian Sea. Stretching over 3,000 kilometers, it is Pakistan’s principal freshwater artery and supports more than 90% of the country’s agricultural activity.

The river system is made up of five major tributaries—the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej—each contributing significantly to the hydrological, ecological, and cultural fabric of the nation. These rivers form the Indus Basin Irrigation System (IBIS), the largest contiguous irrigation system in the world, covering more than 16 million hectares of cultivated land (WAPDA, 2020).

The Jhelum River, rising from Indian-administered Kashmir, flows into Pakistan at Mangla and eventually merges with the Chenab. The Chenab, formed by the confluence of the Chandra and Bhaga rivers in India, joins the Jhelum and later the Sutlej, which itself originates in Tibet and joins the Indus at Mithankot. The Ravi and Beas—while smaller—hold historic and environmental significance, particularly for the Punjab region, which literally means “Land of Five Rivers.”

Collectively, this river system has been central not only to agriculture and settlement but also to cultural identity, spiritual traditions, and trade routes. Despite its ecological wealth, however, the potential for recreational and sustainable tourism around these rivers remains largely underexplored, especially when compared to other countries with prominent river tourism industries.

Socioeconomic and Ecological Importance of the Indus Basin

The Indus Basin is far more than a network of rivers—it is the lifeline of Pakistan’s socioeconomic structure, influencing everything from food security and energy production to regional stability and rural livelihoods. Encompassing over 65% of Pakistan’s land area and supporting more than 220 million people, the basin irrigates one of the most densely cultivated agricultural systems in the world (Lahore School of Economics, 2010).

From the glaciers of Gilgit-Baltistan, which supply over 60% of the Indus flow, to the fertile plains of Punjab and Sindh, the river system plays a central role in Pakistan’s food and water security. The Indus Basin Irrigation System (IBIS) diverts water through an intricate network of barrages, canals, and distributaries, making Pakistan one of the most irrigated countries on the planet. Yet, this dependence also exposes the region to severe climate vulnerabilities, including glacial melt, erratic monsoons, and increased flood risks (World Bank, 2013).

Ecologically, the basin nurtures diverse habitats—from alpine wetlands and riverine forests to mangrove estuaries. These ecosystems support hundreds of bird species, endangered mammals like the Indus river dolphin, and critical fish populations that sustain riverside communities. Despite this richness, water pollution, over-extraction, and habitat degradation continue to threaten biodiversity.

Crucially, the Indus Basin also holds cultural and spiritual significance. Ancient settlements like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa flourished along these waters, shaping early South Asian civilization. Even today, riverbanks are dotted with shrines, festivals, and rituals, marking the rivers as sacred spaces in local belief systems.

Given this multi-dimensional importance, the Indus Basin is not just a site of development planning or hydrological concern—it is a living system with immense potential for ecotourism, cultural exploration, and environmental education. Unlocking this potential requires a shift in perception: from rivers as utilities to rivers as destinations.

What River Tourism in Pakistan Means

River tourism refers to a form of travel that centers around the natural, cultural, and recreational assets of river systems. Globally, river tourism has emerged as a sustainable model that blends environmental conservation, community empowerment, and heritage preservation. In countries like Egypt (Nile cruises), Vietnam (Mekong Delta tours), and France (Seine river experiences), river tourism contributes significantly to local economies while preserving ecological integrity.

In Pakistan, however, the concept of river tourism remains underdeveloped, despite the presence of one of the world’s most extensive river networks. Currently, rivers are seen largely through utilitarian lenses—as sources of irrigation, hydroelectric power, or flood risk zones. But these same rivers also hold the promise of unique ecotourism experiences that can rejuvenate rural economies, foster environmental awareness, and attract both domestic and international travelers.

Imagine gliding through the calm waters of the Chenab River at sunset, with historical forts in the background. Or camping along the Jhelum, with birdwatching tours at sunrise. Or even kayaking in the northern stretches of the Indus, surrounded by majestic peaks. These aren’t fantasies—they are latent opportunities waiting to be recognized and responsibly developed.

River tourism in Pakistan can take many forms:

-

Adventure tourism: white-water rafting, kayaking, and fishing

-

Cultural tourism: heritage walks, riverbank festivals, shrine visits

-

Wildlife and eco-tours: mangrove safaris, wetland birdwatching, dolphin sighting

-

Agro-ecotourism: village stays, farm-to-table experiences, local handicrafts

The key is to anchor these experiences in sustainability and inclusivity, ensuring that local communities benefit economically, culturally significant sites are protected, and natural habitats are preserved. With thoughtful planning, the rivers of Pakistan can offer not just beauty, but meaning—connecting travelers to land, people, and purpose.

Key River-Based Ecotourism Opportunities in Pakistan

1. The Upper Indus – Gilgit-Baltistan

The Upper Indus region is a raw, majestic landscape where glacial rivers carve through steep gorges and ancient villages cling to the cliffsides. Flowing south from Tibet, the Indus gathers strength in Gilgit-Baltistan, absorbing meltwater from over 5,000 glaciers, including some of the largest outside the polar regions.

Tourism in this area is already associated with trekking and mountaineering, but its river tourism potential remains largely unexplored. With careful investment, the region can host:

-

Guided rafting expeditions between Skardu and Gilgit during the summer melt seasons.

-

Eco-camps near Basho Valley and Shigar offer educational retreats on glacier ecology and river dynamics.

-

Cultural storytelling tours in villages like Khaplu and Gulmit showcase oral histories that revolve around the Indus as a giver of life and protector of the valley.

This region is also ideal for eco-documentary tourism, where visitors can witness climate change impacts firsthand—such as glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs)—and interact with indigenous communities pioneering local resilience.

2. Jhelum and Chenab – Punjab’s Historical Heartland

Punjab’s identity is inseparable from its rivers. The Jhelum and Chenab are not just water sources—they are the lifeblood of Punjab’s literature, music, and romance, immortalized in legends like Heer-Ranjha, set along the Chenab. The emotional and historical weight of these rivers makes them perfect for cultural-ecotourism hybrids.

Here, river tourism could include:

-

Riverfront festivals and night cruises in cities like Jhelum, Gujrat, and Sialkot, combining music, history, and food.

-

Farmstay experiences in riverine villages that integrate irrigation-based farming tours, traditional Punjabi cuisine, and handicraft workshops.

-

Restoration of historical ghats and river embankments, offering aesthetic spaces for both locals and tourists to engage with the water.

Additionally, barrages like Trimmu and Marala offer engineered viewing decks and picnic areas, but lack interpretive signage or curated experiences—a gap that presents an immediate opportunity for development.

3. Ravi and Sutlej – The Southern River Corridor

Though diminished in flow due to the Indus Waters Treaty (1960)—which granted exclusive rights of Ravi and Sutlej to India—their ecological significance within Pakistan persists. Seasonal wetlands, floodplains, and sacred sites still flourish along their banks.

Ecotourism potential here is deeply intertwined with restoration and conservation, such as:

-

Creating eco-trails through protected areas like the Head Balloki Wetlands Complex, which hosts migratory birds like the greater flamingo, painted stork, and Siberian crane.

-

Partnering with Sufi networks to develop spiritual eco-tourism, with guided circuits from Baba Farid’s shrine (Pakpattan) to local riverbank meditation centers.

-

Launching river revival drives through school and community engagement, where tourists become participants in cleanup and tree plantation projects along deteriorating embankments.

The Ravi and Sutlej also intersect with heritage trains and rural road trips, making them ideal for integrated slow tourism models.

4. The Indus Delta – Sindh’s Forgotten Frontier

Once a thriving estuarine paradise, the Indus Delta is now facing alarming ecological decline. With drastically reduced freshwater inflow (from 150 MAF to under 10 MAF annually), saltwater intrusion has degraded farmland and pushed communities toward migration. Yet, the delta’s uniqueness remains unmatched in Pakistan’s coastal geography.

Reviving the delta through sustainable tourism could involve:

-

Mangrove boat tours led by trained community guides, sharing indigenous knowledge about Avicennia marina, crab farming, and tidal changes.

-

Development of floating education centers in partnership with organizations like WWF-Pakistan, to raise awareness among tourists and school groups.

-

Establishment of mobile eco-lodges near Keti Bunder, Kharo Chan, and Shah Bundar, operating only in dry seasons to avoid damaging the fragile estuarine soil.

There’s also significant potential for CSR-backed projects: tourism operators can partner with local NGOs and schools to support solar electrification, sanitation, and livelihood training.

Each of these regions offers a different lens into Pakistan’s river ecology and local life. Together, they can support a national river tourism circuit, positioning Pakistan not just as a mountain destination, but as a river-rich, ecologically vibrant nation embracing sustainable tourism.

Policy Landscape and Institutional Support

Despite the ecological, cultural, and economic significance of Pakistan’s rivers, river tourism remains absent from mainstream tourism policy and infrastructure development. The current institutional focus is centered largely on water management, flood mitigation, and agricultural irrigation, leaving tourism potential largely ignored in national frameworks.

The Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, signed between Pakistan and India with World Bank arbitration, divided the use of the eastern (Ravi, Sutlej, Beas) and western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab). While this treaty successfully averted conflict over water for decades, it also framed rivers almost exclusively as geopolitical and agricultural assets (Asjad Imtiaz Ali, 2010). As a result, tourism, environmental sustainability, and cultural preservation were never included in the river governance dialogue.

Agencies such as WAPDA, the Ministry of Climate Change, and Provincial Irrigation Departments maintain control over water-related decisions, but there is little cross-sector collaboration with PTDC, tourism boards, or private ecotourism ventures. While some regions like Gilgit-Baltistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have made strides in promoting adventure tourism, rivers remain peripheral to these strategies.

Moreover, urban and rural development authorities have yet to implement structured riverfront zoning plans that could enable eco-lodges, recreational boating, cultural festivals, or wetland preserves. In contrast, countries like Bangladesh (Sundarbans), Nepal (Trishuli River), and even India (Ganges riverfront redevelopment) have launched river-based tourism strategies that blend conservation, livelihood development, and heritage tourism.

There are, however, promising signs:

-

Water Vision 2025, led by WAPDA, includes references to the ecological importance of river systems.

-

Climate resilience policies from the Ministry of Climate Change emphasize ecosystem preservation, which aligns well with ecotourism objectives.

-

A growing network of community-based tourism startups, NGOs, and educational institutions is piloting nature and culture-based experiences, especially in Gilgit-Baltistan, Punjab’s wetlands, and the Indus Delta.

What’s lacking is a cohesive national framework that treats rivers not only as hydrological challenges but as living landscapes—capable of supporting tourism, education, biodiversity, and heritage.

To fully realize the potential of river tourism in Pakistan, there must be:

-

Policy integration between environmental agencies and tourism departments

-

Investment incentives for sustainable infrastructure development

-

Training programs to empower riverside communities as stakeholders in ecotourism

-

Pilot projects in selected regions to serve as proof-of-concept models

Without these shifts, rivers will remain an untapped asset, flowing through Pakistan not just with water, but with missed opportunity.

Also See: Forest Reserves in Pakistan

Climate Risks and River Tourism

While the potential for river tourism in Pakistan is vast, its development must be viewed through the lens of climate vulnerability. The Indus Basin is already one of the most climate-sensitive regions in South Asia, facing a range of environmental challenges that directly threaten both river systems and the communities that depend on them.

1. Glacial Melt and Water Imbalance

The Upper Indus Basin derives a significant portion of its flow—over 60%—from glacial melt in the Hindukush-Karakoram-Himalaya (HKH) region. Due to global warming, these glaciers are retreating at alarming rates, contributing to Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) that damage infrastructure and erode riverbanks (World Bank, 2013). These events pose serious safety risks for communities and any tourism infrastructure along riverbanks.

2. Flooding and Monsoon Variability

The mid and lower Indus Basin is highly susceptible to seasonal flooding, exacerbated by erratic monsoon behavior. The devastating 2010 floods displaced millions and submerged large sections of Punjab and Sindh. For river tourism to succeed, it must be resilient to seasonal variability, with infrastructure designed for climate adaptation, such as elevated eco-lodges, early warning systems, and flexible seasonal scheduling.

3. Reduced Freshwater Flow and Delta Degradation

Downstream, the Indus Delta faces ecological collapse due to drastically reduced freshwater flow, dropping from around 150 million acre-feet (MAF) annually in the early 20th century to less than 10 MAF today. The result is increased salinity intrusion, loss of agricultural land, mangrove deforestation, and biodiversity decline. These factors make the delta a high-risk, high-urgency zone where tourism can either help or harm, depending on how it is managed.

4. Water Pollution and Waste Management

Many of Pakistan’s rivers—particularly the Ravi and Sutlej—are highly polluted due to untreated industrial effluents, agricultural runoff, and solid waste disposal. Without urgent action, these conditions can make rivers unfit for both aquatic life and tourism. Sustainable river tourism must be paired with river cleanup programs, pollution controls, and education campaigns for both locals and visitors.

The Role of Responsible Tourism in Climate Resilience

Rather than being seen as a threat to ecological balance, tourism—if developed responsibly—can become part of the solution to climate challenges. Here’s how:

-

Awareness & Education: Eco-tourists and nature enthusiasts can become advocates for river conservation, spreading awareness through storytelling, social media, and community interaction.

-

Revenue for Conservation: Tourism revenues can fund reforestation, wetland restoration, and water management programs.

-

Community Resilience: Diversifying riverside economies through tourism can reduce over-reliance on agriculture, which is increasingly vulnerable to drought and flooding.

-

Research and Monitoring: Tourist trails and eco-lodges can double as monitoring sites for academic research and climate impact assessment.

In a climate-stressed future, tourism around rivers must do more than entertain—it must educate, preserve, and empower. River tourism in Pakistan has the potential to become a model for climate-adaptive development, but only if sustainability is embedded in its very foundation.

Recommendations to Boost River Tourism in Pakistan

Unlocking the potential of river tourism in Pakistan requires more than just scenic landscapes or adventurous activities—it calls for a structured, inclusive, and sustainable approach grounded in policy reform, stakeholder collaboration, and community empowerment. Below are actionable recommendations to help transition from potential to practice.

1. Identify and Zone River Tourism Corridors

-

Conduct comprehensive mapping and feasibility studies along major rivers like the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum to identify safe, ecologically stable, and culturally rich zones.

-

Establish “River Tourism Corridors” that integrate natural beauty with historical, spiritual, and ecological significance, similar to how mountain tourism zones are marked in the north.

2. Promote Low-Impact Infrastructure

-

Encourage the development of eco-lodges, floating camps, tent villages, and solar-powered riverboats, especially in Gilgit-Baltistan, Punjab’s headworks, and Sindh’s delta.

-

Avoid concrete-heavy resorts that disrupt riverbanks—focus instead on modular, mobile, or seasonally adaptive structures that blend with the landscape.

3. Involve Local Communities as Primary Stakeholders

-

Train local youth as eco-guides, nature interpreters, river stewards, and cultural docents through capacity-building workshops.

-

Enable riverside communities to run guesthouses, local cuisine cafes, and handicraft stalls, ensuring direct income flow to underserved rural populations.

4. Integrate Policy Across Tourism, Climate, and Water Sectors

-

Establish interdepartmental coordination between PTDC, WAPDA, MoCC, and provincial tourism ministries to create a unified River Tourism Development Framework.

-

Embed river tourism into Pakistan’s National Tourism Strategy, Climate Resilience Plans, and Wetland Management Policies.

5. Pilot River Tourism Projects in High-Potential Sites

Start with 3–5 pilot projects across diverse ecological zones, such as:

-

Skardu–Gilgit rafting corridor

-

Chenab River agro-eco-trail near Jhang and Trimmu Barrage

-

Birdwatching and wetland lodges in Head Balloki

-

Indus Delta mangrove safaris and floating classrooms in Keti Bunder

These pilots can serve as models for scalability, incorporating learnings into broader national expansion.

6. Position River Tourism as a Tool for Conservation

-

Design tourism programs that fund environmental restoration, such as native tree planting, wetland revival, and riverbank erosion control.

-

Build partnerships with organizations like WWF-Pakistan, UNDP, and local academic institutions to monitor environmental impact and run conservation awareness campaigns.

7. Leverage Digital Platforms and Branding

-

Promote curated river experiences through platforms like TrulyPakistan, positioning them not just as recreational getaways but as cultural-ecological journeys.

-

Use 360° video content, river tourism trails, interactive maps, and storytelling to attract both domestic and international eco-travelers.

Reviving Rivers as Destinations

The rivers of Pakistan have sustained civilizations, nurtured economies, and inspired legends for millennia. Today, they stand at the crossroads of crisis and opportunity. While climate change, pollution, and neglect threaten these vital ecosystems, they also offer a new path forward—river tourism that is sustainable, inclusive, and conservation-driven.

From the glacier-fed torrents of Gilgit-Baltistan to the languid, storied currents of Punjab and the biodiversity-rich delta of Sindh, Pakistan’s river systems embody both natural wonder and cultural depth. Yet, unlike other nations that have embraced their waterways as tourist assets, Pakistan has yet to recognize the full potential of its riverine landscapes.

River tourism in Pakistan is not just about rafting or sightseeing—it’s about reviving forgotten frontiers, supporting local communities, and fostering a national identity grounded in harmony with nature. It is about creating experiences that allow travelers to understand the soul of the country, not from highways or airports, but from the quiet rhythm of a riverbank at dawn, the sound of paddles in water, or the stories of villagers who’ve lived beside these rivers for generations.

To move forward, Pakistan must shift its perspective: from treating rivers solely as utilitarian assets to embracing them as living destinations—vibrant with ecological, cultural, and spiritual meaning. This requires collaboration across government, civil society, academia, and tourism entrepreneurs to build a framework where ecotourism and water resilience go hand in hand.

If developed with care, river tourism can become a catalyst not only for economic growth but for environmental stewardship, cultural preservation, and global engagement. Pakistan’s rivers are already flowing with history. It’s time they also follow the vision.

References

-

Development of the Indus River System Model to Evaluate Reservoir Operations in Pakistan.

Water (MDPI), 2021.

https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/13/7/895 -

Pakistan: Indus Basin Water Strategy – Past, Present and Future.

Lahore School of Economics, 2010.

https://lahoreschoolofeconomics.edu.pk/assets/uploads/lje/Volume15/09_Dr_Shahid_Chaudhry_EDITED_TTC11-10-10.pdf -

Schematic Diagram of the Indus River Basin (Source: WAPDA).

Planning Commission of Pakistan.

https://pc.gov.pk/uploads/plans/Ch20-Water1.pdf -

Transboundary Indus Basin: Science Policy Review.

JSTOR / Overseas Development Institute, 2019.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep15851.6.pdf -

Analysis of the Indo-Pak Indus Waters Treaty 1960.

Pakistan Engineering Congress, 2010.

https://pecongress.org.pk/images/upload/books/12-Asjad%20Imtiaz%20Ali.pdf -

Water Management in Pakistan’s Indus Basin.

IWA Publishing, 2021.

https://iwaponline.com/wp/article/23/6/1329/84494/Water-management-in-Pakistan-s-Indus-Basin -

Indus Basin of Pakistan – Impacts of Climate Risks on Water and Agriculture.

World Bank, 2013.

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/650851468288636753/pdf/Indus-basin-of-Pakistan-impacts-of-climate-risks-on-water-and-agriculture.pdf -

Indus River System: Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas & Sutlej.

PMF IAS Geography Guide.

https://www.pmfias.com/indus-river-system-jhelum-chenab-ravi-beas-satluj/

One thought on “River Tourism in Pakistan – Exploring the Indus Basin”