Understanding Sufi Music Traditions

Sufi music occupies a profound space within Islamic mysticism, serving as both an expression of devotion and a method of spiritual elevation. Rooted in the teachings of Sufism—an inward, esoteric dimension of Islam—it seeks to foster a direct and intimate relationship with the Divine. Unlike ritualistic or dogmatic approaches to religion, Sufi practice emphasizes love, surrender, and personal experience of God’s presence. In this context, music becomes far more than mere artistic expression; it transforms into a sacred vessel through which seekers attempt to bridge the gap between the human soul and the Divine.

Central to Sufi music is its role in dhikr (remembrance), a spiritual practice where participants repeatedly invoke the name of God or recite sacred phrases to cultivate mindfulness of His presence. The rhythmic repetition in music mirrors this act of remembrance, allowing listeners and performers alike to synchronize their hearts with the Divine pulse. The melodies, often accompanied by poetry rich in metaphor and symbolism, guide individuals into states of heightened emotional and spiritual receptivity.

Scholars have described Sufi music as a form of spiritual technology—a structured pathway leading toward ecstatic union (wajd). This state of wajd is not simply emotional excitement but a profound dissolution of the self, where the soul experiences unity with the Divine essence. The carefully designed musical progressions, increasing tempo, and repetitive refrains serve to draw participants deeper into this trance-like state. Instruments, vocals, and lyrics all work synergistically to dissolve the boundaries of ordinary consciousness, creating moments where individuals feel completely enveloped by Divine presence.

Thus, Sufi music traditions serve not merely as cultural artifacts but as living practices that continue to nurture the spiritual journeys of countless seekers across centuries.

Historical Evolution of Sufi Music Traditions

The origins of Sufi music are deeply embedded in the broader historical evolution of Islamic mysticism. While early Islamic orthodoxy often debated the permissibility of music, Sufi orders gradually embraced it as a legitimate means of spiritual elevation. By the 8th and 9th centuries, as Sufi thought matured, music began to take on a central role in certain mystical circles, especially in regions influenced by Persian, Turkic, and Central Asian traditions.

As Sufi orders spread across the Muslim world, their musical practices evolved alongside local cultures. When Sufi missionaries and saints arrived in South Asia between the 11th and 13th centuries, they encountered rich musical traditions in the Indian subcontinent. Rather than rejecting these local forms, many Sufi masters embraced and adapted them, resulting in unique South Asian expressions of Sufi music. This cultural syncretism gave rise to forms such as Qawwali, Kafi, and regional folk adaptations, blending Persian, Arabic, Turkish, and indigenous South Asian musical elements.

One of the most significant contributors to this transformation was Amir Khusro, a 13th-century musician, poet, and scholar often credited as the father of Qawwali. His work laid the foundation for a form of devotional music that combined the poetic sophistication of Persian with the melodic structures of Indian classical and folk traditions. Through Khusro’s innovation, Sufi music became a powerful bridge between different cultures, languages, and spiritual expressions.

In Sindh, Pakistan, Sufi music took on an even more localized flavor. The shrines of saints like Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai and Lal Shahbaz Qalandar became hubs where music was not only performed but woven into the very fabric of daily spiritual life. Here, regional languages such as Sindhi, Punjabi, and Balochi served as the vehicles for expressing Sufi poetry, while indigenous instruments like the ektara, damburo, and dholak carried the sacred rhythms forward.

Throughout its historical journey, Sufi music traditions have shown remarkable adaptability. They have absorbed influences from various cultural contexts while preserving their core function: to serve as a means of connecting the human soul with the Divine. In every era, Sufi music has remained a living tradition, continually evolving while anchoring its practitioners in timeless spiritual truths.

Key Forms and Genres in Sufi Music

Over centuries, Sufi music has developed multiple distinct forms, each deeply rooted in regional cultures yet unified by the shared goal of spiritual elevation. In South Asia, three major expressions have become central to Sufi music traditions: Qawwali, Kafi, and the more contemporary adaptations blending traditional and modern sounds.

Qawwali — The Core of South Asian Sufi Music

Qawwali stands as one of the most recognizable and spiritually potent forms of Sufi music in Pakistan, India, and the wider South Asian diaspora. Its historical roots trace back to the legendary 13th-century figure Amir Khusro, whose innovations shaped Qawwali into its distinct identity. Drawing from Persian, Arabic, Turkish, and Indian musical vocabularies, Khusro’s work allowed Qawwali to serve not only as devotional music but also as a sophisticated art form capable of conveying complex theological and philosophical ideas.

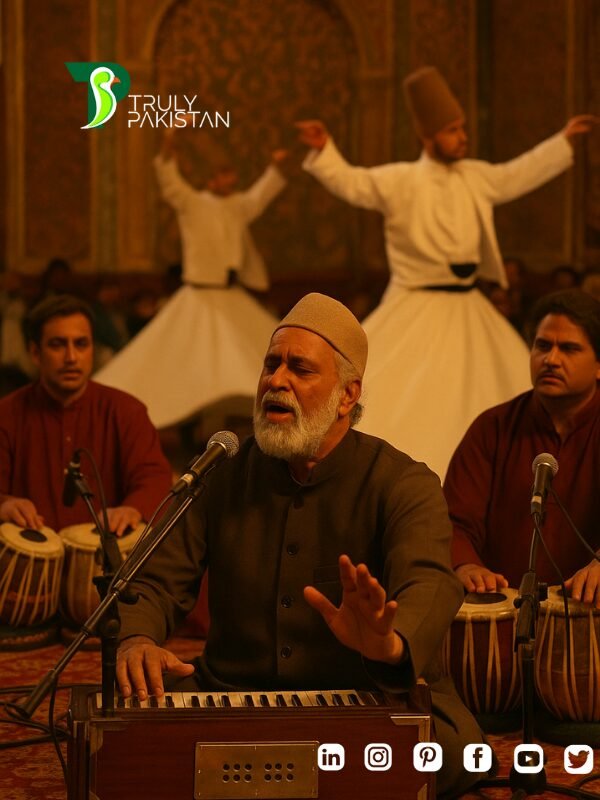

Performed by trained ensembles called Qawwals, the music is highly participatory. The lead singer, supported by a chorus (humnawa), harmonium players, tabla or dholak drummers, and hand clappers, create an immersive sonic experience. The compositions often build gradually, with repeating refrains, intensifying tempo, and spontaneous improvisation designed to lead both performers and audiences into a state of spiritual ecstasy (wajd).

Within Pakistan, the lineage of Qawwal Bachche, originating from the Delhi Gharana, has preserved and refined the tradition for centuries. Families like the Sabri Brothers and the late Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan have played pivotal roles in popularizing Qawwali globally, introducing it to diverse audiences while maintaining its spiritual core.

Kafi and Sufi Folk Traditions

In addition to Qawwali, regional folk expressions such as Kafi have become central to Sufi music traditions in Pakistan. Originating primarily in Punjab and Sindh, Kafi features poetry by revered mystic poets like Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Bulleh Shah, Sachal Sarmast, and Hazrat Sultan Bahu. These poets explored themes of Divine love, separation (hijr), union (visal), and surrender through simple yet profound verses that resonate deeply with local communities.

Unlike the ensemble nature of Qawwali, Kafi performances often involve solo or duo artists accompanied by traditional instruments like the ektara, sarangi, dholak, or damburo. The stripped-down format allows the raw emotional depth of the lyrics to shine, engaging audiences in both personal reflection and communal experience.

The shrines of Sindh, particularly those of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai and Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, serve as vibrant spaces where Kafi and folk Sufi music flourish. Here, music is not reserved for special occasions but becomes part of daily spiritual life, echoing through prayer gatherings, urs festivals, and communal rituals.

Modern Interpretations — Coke Studio and New-Age Sufism

In recent decades, Sufi music traditions have undergone a contemporary revival, reaching younger audiences and global listeners through digital media platforms. Among the most influential drivers of this resurgence is Pakistan’s Coke Studio, which has reimagined Sufi poetry by blending it with modern musical arrangements, Western instruments, and cross-genre collaborations.

Through its innovative reinterpretations of classical compositions like “Tajdar-e-Haram,” “Chaap Tilak,” and “Allah Hoo,” Coke Studio has introduced Sufi themes to millions of young listeners, both within Pakistan and across the global diaspora. These modern renditions often retain the spiritual depth of the original poetry while adding fresh sonic layers that appeal to contemporary sensibilities.

However, this modernization has also sparked debates within scholarly and spiritual communities. While many praise Coke Studio for preserving and promoting Sufi heritage, others caution against the risk of commercialization diluting the profound spiritual essence that lies at the heart of Sufi music traditions. Balancing accessibility with authenticity remains an ongoing challenge for modern interpreters.

The Spiritual Philosophy Behind Sufi Music

At the heart of Sufi music traditions lies a profound spiritual philosophy that transcends mere performance. Sufi practitioners view music not simply as entertainment but as a sacred instrument capable of guiding the soul closer to Divine reality. This connection between music and spirituality is deeply rooted in the mystical understanding of the human relationship with God—a bond defined by love, longing, and ultimate surrender.

A central concept within this philosophy is Sama, which literally means “listening.” In Sufi practice, Sama refers to sacred listening sessions where music, poetry, and rhythm are used to awaken the heart’s yearning for God. These gatherings are not passive concerts but highly intentional acts of devotion where participants engage deeply with every note, lyric, and vibration. The aim is to move beyond the physical world and enter a state of spiritual absorption, where worldly distractions fall away, leaving only the seeker and the Divine.

The culmination of Sama often leads participants to a state known as wajd—an ecstatic spiritual condition where the boundaries of the self dissolve. In wajd, individuals may experience overwhelming emotions, physical movement, or even spontaneous expressions of joy, weeping, or trance-like states. This is not seen as loss of control, but as the soul’s response to the overwhelming presence of Divine love.

The structured progression of Sufi music plays a vital role in this journey. Repetitive rhythms, ascending melodic lines, and emotionally charged poetry all serve to gradually heighten the listener’s spiritual receptivity. The use of metaphoric language—such as references to the beloved, wine, or intoxication—allows complex theological ideas to be expressed in accessible, emotionally resonant terms. These symbols reflect the mystic’s desire to become “drunk” on Divine love, surrendering completely to God’s will.

This philosophy underscores why many Sufi orders embrace music despite historical debates within Islamic jurisprudence regarding its permissibility. For Sufis, when approached with sincerity and spiritual intention, music becomes a tool for tazkiyah (purification of the soul), helping the seeker transcend ego and experience Divine unity.

Even today, this philosophy remains at the core of Sufi musical gatherings across Pakistan, from intimate zikr circles to large public festivals at shrines, where thousands gather to participate in the timeless dance between melody and mysticism.

Sufi Music Traditions in Sindh: A Case Study

Among the many regions where Sufi music flourishes, Sindh holds a particularly important place. Often referred to as the “land of saints and shrines,” Sindh has served for centuries as a vibrant center of Sufi thought, poetry, and musical expression. The distinct flavor of Sindhi Sufism reflects a deep integration of local culture, language, and history, offering a powerful example of how Sufi music traditions adapt and thrive within regional contexts.

At the heart of Sindh’s Sufi culture stands the towering figure of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai (1689–1752), whose poetry continues to define the region’s spiritual and musical landscape. His magnum opus, Shah Jo Risalo, is a rich collection of poetic verses that explore themes of Divine love, human suffering, separation, longing, and ultimate union with God. Shah Latif’s use of Sindhi language and local folklore made his teachings deeply accessible to common people, allowing spiritual wisdom to reach far beyond scholarly circles.

Musically, Shah Latif’s poetry is often performed in the Kafi tradition, accompanied by indigenous instruments like the tamburo (a drone string instrument unique to Sindh), ektara, dholak, and sarangi. The performances are typically intimate, emphasizing emotional depth and simplicity rather than elaborate orchestration. Through these performances, Shah Latif’s verses continue to serve as a living dialogue between the human soul and the Divine.

The shrine culture of Sindh also plays a central role in preserving and promoting Sufi music traditions. The shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan Sharif is one of the most iconic spiritual sites in Pakistan. Here, the rhythmic beating of the dhol (drum), continuous chanting, and devotional dancing (dhamaal) create a powerful communal experience of spiritual ecstasy. Pilgrims from across Pakistan and beyond gather to participate in these rituals, often losing themselves in states of wajd, united by the shared pursuit of Divine presence.

Sindh’s Sufi music traditions also serve important social functions. In a society often fragmented by political, ethnic, or sectarian tensions, these gatherings provide inclusive spaces that transcend boundaries. People of various backgrounds—regardless of class, gender, or religious sect—join together in common devotion, embodying the Sufi principles of tolerance, unity, and universal love.

Even in the modern era, Sindh’s Sufi music traditions continue to evolve. Contemporary Sindhi artists draw upon this rich heritage, incorporating elements of Kafi, Qawwali, and modern fusion to engage younger generations. Yet at their core, these traditions remain deeply anchored in the timeless spiritual teachings passed down through centuries of Sufi practice.

Globalization, Media, and the Changing Landscape of Sufi Music

In recent decades, globalization and the rise of digital media have profoundly reshaped the landscape of Sufi music traditions. What was once largely confined to spiritual gatherings, shrines, and regional festivals has now reached global audiences, opening new opportunities for preservation, revival, and reinvention—but also introducing complex challenges around authenticity, commercialization, and cultural appropriation.

One of the most visible drivers of this transformation is Pakistan’s widely popular Coke Studio platform. By blending Sufi poetry with modern musical genres—such as pop, rock, electronic, and orchestral arrangements—Coke Studio has introduced iconic Sufi compositions to millions of young listeners worldwide. Renditions of classics like “Tajdar-e-Haram,” “Chaap Tilak Sab Cheen,” and “Allah Hoo” have not only revived interest in Sufi music but also allowed it to cross linguistic and cultural boundaries.

Coke Studio’s approach is both innovative and controversial. On one hand, it has successfully democratized access to Sufi music traditions, making centuries-old poetry relevant to newer generations who might otherwise have remained disconnected from their spiritual and cultural heritage. On the other hand, critics argue that such fusion risks stripping the music of its spiritual gravitas, turning deeply sacred traditions into market-driven entertainment products.

Beyond Coke Studio, the global spread of Sufi music is further accelerated by digital platforms such as YouTube, Spotify, and social media. International collaborations featuring South Asian Qawwals and global artists have introduced Sufi sounds to concert halls and festivals from Europe to North America. This increased visibility has led to renewed scholarly interest, tourism to Sufi shrines, and a global recognition of Pakistan’s rich spiritual heritage.

Yet, globalization also brings the risk of cultural dilution. In some cases, Sufi music is presented as exotic or aesthetic without proper understanding of its spiritual depth, reducing it to mere performance divorced from its devotional context. There is a growing concern among traditional practitioners that as Sufi music becomes increasingly commercialized, its transformative power as a spiritual practice may be lost.

Nevertheless, the global reach of Sufi music traditions also offers opportunities for cross-cultural dialogue, interfaith understanding, and peace-building—aligning with the very values that Sufism has long embodied. When approached with respect, knowledge, and sincerity, modern platforms can serve not as replacements but as powerful extensions of centuries-old spiritual traditions.

The Role of Sufi Music in Promoting Peace and Social Harmony

Beyond its artistic and spiritual significance, Sufi music traditions have long played a powerful role in promoting peace, tolerance, and social cohesion—both within Pakistan and globally. In an era where societies are often marked by division, conflict, and extremism, Sufi music offers an alternative narrative rooted in love, inclusivity, and the shared human longing for the Divine.

Central to Sufism is the idea of universal love—the belief that every soul carries within it a spark of the Divine and that true spirituality transcends religious, ethnic, or cultural differences. This ethos is vividly expressed in the poetry of Sufi saints like Bulleh Shah, Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai, Sachal Sarmast, and Rumi, whose verses call for unity over division, and compassion over judgment. Through music, these messages become more than words; they become shared emotional experiences that unite audiences across backgrounds.

The inclusive nature of Sufi music gatherings—particularly at shrines and festivals—reflects these principles in action. People from all walks of life, regardless of class, gender, or sect, gather at places like Sehwan Sharif, Bhit Shah, and Data Darbar to participate in dhamaal, Qawwali, and devotional singing. These communal spaces serve as powerful reminders of Pakistan’s pluralistic cultural roots, where diversity is not merely tolerated but celebrated as part of spiritual life.

This aspect of Sufi music has gained increasing attention in policy and academic circles, particularly in the context of countering violent extremism. In regions where extremist ideologies attempt to impose rigid, exclusionary worldviews, Sufi music traditions offer a peaceful counterbalance—emphasizing inner transformation rather than outward imposition, and love over hatred. Programs promoting Sufi music among youth, such as those discussed in recent academic studies and national media, have been recognized as vital tools in fostering resilience against radicalization.

Moreover, Sufi music serves as a form of interfaith dialogue, resonating with audiences beyond the Islamic world. Its universal themes of love, surrender, and spiritual longing are easily understood across religious and cultural divides, allowing Sufi performances to become sites of cross-cultural engagement and mutual respect.

In a rapidly changing world, where polarization threatens to erode the social fabric, the timeless values embedded within Sufi music traditions remain deeply relevant. By nurturing empathy, compassion, and a shared sense of humanity, Sufi music continues to fulfill one of its most profound roles: healing both individual hearts and collective societies.

Sufi Music Traditions as a Living Spiritual Heritage

Also See: Folk Music of Pakistan

Sufi music traditions stand today as a living spiritual heritage—bridging centuries, cultures, and communities. Far beyond performance or entertainment, these musical forms carry within them the deep currents of human longing for connection with the Divine. They offer not only a path of individual transformation but also serve as communal rituals that reinforce values of love, unity, and peace.

Throughout history, Sufi music has proven its remarkable adaptability. Whether in the intimate gatherings of Sindh’s shrines, the global stages of Qawwali legends, or the digital soundscapes of Coke Studio, the essence of Sufi music remains rooted in its ability to touch the human soul. Its power lies in its universality—a language of devotion that requires no translation, inviting listeners from every background into its sacred space.

Yet, as this tradition continues to evolve, it faces the dual responsibility of preserving its spiritual authenticity while engaging with modern platforms and audiences. Efforts to promote and study Sufi music must therefore balance accessibility with depth, ensuring that the core values of humility, surrender, and Divine love remain at its heart.

For Pakistan, Sufi music traditions represent not only a rich cultural legacy but also a vital social resource. In a world increasingly marked by polarization and unrest, these traditions offer powerful counter-narratives rooted in tolerance, coexistence, and shared humanity. By investing in their preservation, education, and responsible promotion, Pakistan has the opportunity to present to the world not just its cultural wealth, but its enduring commitment to peace through spiritual heritage.

In the timeless echoes of Sufi poetry and song, we are reminded that while the forms may change, the message remains eternal: the journey of the soul toward Divine love knows no boundaries.

📌 References / Research Sources

-

University of Bern (Doctoral Research): Sufi Heritage in Sindh, Pakistan: Discourse, Representations and Performance

Read here -

Wajiha Ather Naqvi (LAHP Research): Qawwali Unbound: A study of Qawwali in Pakistan (1947–present) through the Qawwal Bachche

Read here -

Barbican: An Introduction to Sufi Music

Read here -

NUML Journal: Coke Studio Sufi Singing and the New Age Spirituality by Kalsoom Qaisar & Dr. Farheen Ahmad Hashmi

Read here -

Scribd: Promotion of Sufism as the New Age Spirituality: Analyzing the Role of Coke Studio

Read here -

Associated Press of Pakistan (APP): Inculcating true essence of Sufi music among youngsters vital for promoting peace

Read here