UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Pakistan: A Complete List

Pakistan is a land where the echoes of ancient civilizations, empires, and spiritual traditions still linger in the architecture, landscapes, and cultural footprints left behind. From the sun-baked ruins of one of the world’s earliest urban settlements to Mughal masterpieces that fuse art with engineering, UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Pakistan offer a powerful narrative of resilience, innovation, and diversity.

This blog takes you on a journey through six of Pakistan’s most remarkable UNESCO sites, each recognized not only for its historical importance but also for its unique contribution to human civilization. Whether you’re a traveler, historian, cultural enthusiast, or student, these sites represent stories that go beyond borders—stories that shaped not just South Asia, but the course of global heritage.

Let’s explore the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Pakistan—from the Indus Valley to the Mughal courts, and from ancient monasteries to fortified citadels—each site a chapter in the ongoing story of our shared past.

1. 🏛️ Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro

Picture by: https://carta.guide/

The Archaeological Ruins at Moenjodaro, located in Sindh, Pakistan, are among the most iconic remnants of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization—one of the world’s earliest urban cultures. These ruins stand as a remarkable example of early city planning, civic infrastructure, and socio-cultural advancement that dates back over 4,500 years. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980, Mohenjo-Daro continues to serve as a silent yet powerful reminder of a lost civilization that rivaled its contemporaries in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.

📍 Location and Geographical Importance

Mohenjo-Daro—meaning “Mound of the Dead” in Sindhi—is situated about 28 kilometers from Larkana and approximately 510 kilometers northeast of Karachi, on the right bank of the Indus River. The city’s location wasn’t just symbolic—it was strategic. Nestled in a fertile plain and near a major water source, it offered ideal conditions for agriculture, trade, and settlement sustainability.

🏗️ Historical Significance and Rediscovery

Built around 2500 BCE, Moenjodaro was one of the major urban centers of the Indus Valley Civilization, which extended across modern-day Pakistan and northwest India. The city was rediscovered in 1922 by archaeologist R.D. Banerji of the Archaeological Survey of India, bringing to light a long-forgotten culture whose sophistication took historians by surprise.

Unlike other ancient cities built to glorify empires or kings, Mohenjo-Daro’s design reflects a society focused on civic order, social equity, and urban efficiency. The absence of grand temples or royal palaces indicates a democratic or egalitarian setup, where governance may have been based on trade councils or priestly elites.

🏙️ Urban Planning & Architecture

What makes Mohenjo-Daro truly exceptional is its advanced urban layout, far ahead of its time.

Divided into Two Main Sectors:

-

Citadel (Western Sector): Built on an artificial mound, the citadel housed significant public structures such as:

-

The Great Bath

-

Granaries

-

Assembly halls

-

Religious platforms

-

This elevated area likely served administrative or ceremonial purposes.

-

Lower City (Eastern Sector): This was the residential and commercial heart of the city. It followed a meticulous grid layout, with wide roads intersecting at right angles. Houses, shops, and workshops were made with uniformly sized baked bricks, showcasing consistency in construction standards.

Construction Techniques:

Walls were built using sun-dried or kiln-fired bricks with bitumen and lime mortar. Buildings often had flat roofs, internal courtyards, and multiple rooms, suggesting thoughtful architectural design that prioritized ventilation, privacy, and communal space.

Sanitation and Water Supply:

Perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of Moenjodaro was its drainage system. Covered drains lined the main streets and were connected to individual homes. Most residences had access to private wells, and waste water was directed through a network of clay pipes and stone-covered channels—making it one of the earliest known examples of public sanitation.

🛕 Iconic Structures

Several structures within the ruins have captured global scholarly attention:

🛁 The Great Bath

Measuring 12 meters long, 7 meters wide, and 2.4 meters deep, the Great Bath is believed to be the earliest public water tank in human history. Made from tightly fitted bricks and sealed with bitumen, it features a central pool surrounded by verandahs and staircases. It may have been used for ritual purification, reflecting the cultural and spiritual values of the time.

🏚️ The Granary

A massive structure interpreted as a storage facility, indicating the city’s role in trade and food security. Its design includes air-ducts under the floors for ventilation—an innovation not seen in many ancient societies.

🏠 Residential Buildings

Homes ranged from modest single-room dwellings to elaborate multi-room houses with private wells, toilets, and bathing areas. The presence of these facilities within households highlights a commitment to personal hygiene and domestic order.

🗿 Artifacts & Cultural Expression

Mohenjo-Daro has yielded thousands of artifacts, many of which are now housed in museums across Pakistan and internationally. These include:

-

Dancing Girl Statue: A famous bronze figurine standing just 10.5 cm tall, this sculpture of a poised young woman adorned with bangles reflects the Indus people’s mastery in metallurgy and expressive art.

-

Pashupati Seal: A steatite seal depicting a horned deity seated in a yogic posture, flanked by animals. Many scholars interpret this as an early form of the Hindu god Shiva, indicating proto-religious symbolism.

-

Indus Script: Despite extensive study, the symbols found on seals and pottery remain undeciphered, suggesting a lost language that once facilitated record-keeping, administration, and communication across the civilization.

⚠️ Conservation Challenges

Despite its historic importance, the Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro are gravely endangered.

Environmental Threats:

-

Rising water tables have caused salt seepage, damaging foundations and bricks.

-

Erosion from the Indus River poses a constant threat to the site’s structural integrity.

-

Climate variability, including monsoon damage, exacerbates decay.

Human Impact:

-

Unregulated tourism, neglect, and insufficient funding have made preservation difficult.

-

Parts of the site have been partially restored using modern materials, which risk compromising its authenticity.

Preservation Efforts:

UNESCO-led interventions in the 1970s included:

-

Mud-capping techniques to protect exposed walls

-

Re-routing drainage systems

-

Structural reinforcements

However, consistent long-term management remains a challenge that requires both government commitment and global heritage support.

🌍 Why Mohenjo-Daro Still Matters

The Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro aren’t just stones and bricks—they are an enduring dialogue between the past and present. They remind us that urban civility, hygiene, and planning are not modern inventions. They reflect a time when humanity, without electricity or modern machinery, was still able to build cities of remarkable order, function, and elegance.

For historians, conservationists, and tourists, Mohenjo-Daro is not just a site—it’s a legacy worth preserving, studying, and celebrating.

2. 🏛️ Taxila: A Crossroads of Civilizations

Nestled in the Margalla Hills region of northern Punjab, Taxila—known in ancient texts as Takṣaśilā—stands as one of South Asia’s greatest archaeological treasures. Once a thriving hub of spiritual, educational, and commercial activity, Taxila tells the story of a city where civilizations collided and coexisted—from the Achaemenid Persians and Indo-Greeks to the Mauryans, Scythians, and Kushans.

This historic site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980, under criteria (iii) and (iv), recognizing its cultural, educational, and architectural significance across centuries.

📍 Location and Historical Setting

Taxila is located approximately 25 kilometers northwest of Islamabad-Rawalpindi, situated just off the Grand Trunk Road, one of the oldest and longest major roads in Asia. Its strategic location along this ancient trade route contributed to its emergence as a vital center of commerce, culture, and knowledge in the Gandhāra region.

🏗️ Historical Significance

Founded as early as the 6th century BCE, Taxila evolved through multiple civilizations. Its longevity and cultural layering are unparalleled. The city became a center of Hindu, Buddhist, and later Greco-Bactrian influence, renowned not only for its architecture but also as a place of philosophical discourse and learning.

Greek historians such as Strabo and Arrian wrote of Taxila’s splendor, while Buddhist texts describe it as a hub of monastic education, where great teachers like Chanakya (Kautilya) and even the Buddha himself may have passed through during their lifetimes.

🏙️ Urban Evolution

Taxila is not a single city but a landscape of ruins spread across various sites that reflect different phases of history. The following major settlements highlight the city’s evolution:

-

Saraikala: The oldest known phase of occupation, dating back to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. Excavations have revealed tools, pottery, and traces of early settlement.

-

Bhir Mound: Believed to be the original city of Taxila, dating to the 6th century BCE. It was the administrative capital during the Achaemenid Empire and home to rudimentary street layouts, mud-brick houses, and coin hoards.

-

Sirkap: Constructed in the 2nd century BCE by the Indo-Greeks, this city showcases a unique fusion of Greek and Indian architecture. The “Double-Headed Eagle Stupa” is one of the site’s most iconic features, symbolizing cross-cultural artistic syncretism.

-

Sirsukh: The last known city at Taxila, built by the Kushan Empire in the 1st century CE. With a fortified wall and grid layout, it reflected more advanced urban planning but was later abandoned due to invasions or natural disasters.

🛕 Notable Structures

Taxila’s layered heritage comes alive in the diversity of its monuments, from Buddhist monasteries to Greek temples:

-

Dharmarajika Stupa: Built by Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE, this massive stupa enshrined relics of the Buddha and became a major pilgrimage site. Its ruins still reveal votive stupas and carved stonework.

-

Jaulian Monastery: Located atop a hill, Jaulian is among the most well-preserved monastic complexes in the region. Intricate stone sculptures, prayer halls, and meditation cells offer insights into monastic life and Gandhāran religious artistry.

-

Jandial Temple: A rare example of Hellenistic architecture, this temple, with its Ionic columns, is believed to have been dedicated to either a Greek deity or Zoroastrian fire worship, reflecting Taxila’s pluralistic spirit.

-

Taxila Museum: Established in 1918, this museum houses thousands of artifacts excavated from the region, including Buddha statues, Gandhāran reliefs, coins, jewelry, and tools, forming a rich visual narrative of the city’s past.

🗿 Cultural Insights

A Global University of the Ancient World

Taxila is often described as one of the first universities in the world, attracting students from as far as China, Mesopotamia, and Greece. Disciplines taught included philosophy, mathematics, medicine, politics, astrology, and military strategy.

Gandhāran Art and Architecture

The art unearthed in Taxila, especially from Jaulian and Dharmarajika, is considered part of the Gandhāra school, which combined Greek realism with Indian spiritual themes. Buddha statues from this era are characterized by wavy hair, Greco-Roman robes, and serene expressions.

⚠️ Conservation and Preservation

Like many ancient sites in Pakistan, Taxila faces growing threats:

-

Urban Encroachment: Nearby construction and infrastructure projects have encroached upon some of the outlying mounds and buffer zones.

-

Looting and Vandalism: Illegal excavations and theft of antiquities have been reported over the decades.

-

Environmental Wear: Natural erosion, seismic activity, and weathering have taken a toll on exposed ruins.

Preservation Initiatives:

-

The Government of Pakistan and UNESCO continue to collaborate on documentation, fencing, and partial restorations.

-

Efforts are underway to digitize site maps, improve visitor management, and raise awareness through academic partnerships.

🌍 Why Taxila Still Matters

The Archaeological Ruins of Taxila are not merely remnants of a lost era—they represent the birthplace of knowledge-sharing in Asia, a confluence of empires, and the sacred footprint of religious harmony.

As a World Heritage Site, Taxila reminds us that Pakistan is not just home to natural beauty, but also to civilizations that shaped human thought, culture, and belief systems across continents. For scholars, pilgrims, and explorers alike, Taxila remains a gateway to a rich and layered past.

3. 🏛️ Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Neighbouring City Remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol

Picture by: https://www.dawn.com/

Perched dramatically on a hilltop in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, the Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi, along with the ancient city remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol, form one of the most awe-inspiring and best-preserved monastic sites from the early centuries of Buddhism in the region. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 under criterion (iv), these sites embody the architectural and spiritual legacy of the Gandhāra Civilization, where Indian and Greco-Roman influences seamlessly merged.

📍 Location and Setting

-

Takht-i-Bahi is located approximately 16 kilometers northwest of Mardan city, standing at an elevation of 152 meters on a rugged hill. This strategic placement not only offered protection from invasions but also symbolized spiritual elevation.

-

Sahr-i-Bahlol, about 5 kilometers away, sits on a fertile plain, spread across a 9.7-hectare mound, and served as an ancient fortified settlement during the Kushan period.

🏗️ Historical Significance

Dating back to the early 1st century CE, both sites played a central role in Buddhist learning, spirituality, and community life. Their architecture and layout reflect the maturity of Gandhāran design, as well as the socio-religious dynamics of a time when Buddhism was flourishing across Central and South Asia.

The name “Takht-i-Bahi” translates to “Throne of the Water Spring”, possibly referencing the natural springs that once flowed nearby—symbols of life and purity in Buddhist philosophy.

🛕 Takht-i-Bahi Monastic Complex

This hilltop monastery is an architectural masterpiece, meticulously carved into the terrain using diaper masonry techniques—a hallmark of Gandhāran stonework, where locally sourced stone blocks were laid in lime and mud mortar.

The layout is divided into functional zones, each reflecting aspects of monastic discipline and meditative living:

-

Stupa Court: The spiritual heart of the complex, this open courtyard is surrounded by votive stupas where monks and devotees could offer prayers and walk in meditation.

-

Monastic Cells: Dozens of small chambers with verandahs, serving as individual living quarters for monks, embody the simplicity of Buddhist ascetic life.

-

Assembly Hall: A communal gathering space used for teachings, rituals, or community discussions.

-

Meditation Chambers: Isolated rooms designed to encourage silence, reflection, and inner awakening.

-

Covered Walkways: These stone-paved corridors connect the entire complex, allowing movement during all seasons and weather conditions.

Thanks to its elevated location, Takht-i-Bahi avoided most foreign invasions and natural destruction, making it one of the best-preserved Buddhist monasteries in all of South Asia.

🏙️ Sahr-i-Bahlol: The Fortified Companion Settlement

Just a short distance away lies the ancient city of Sahr-i-Bahlol, a now-ruined urban settlement from the Kushan dynasty era (1st–3rd century CE). Unlike the spiritual aura of Takht-i-Bahi, Sahr-i-Bahlol served more administrative and residential purposes.

Key features include:

-

Defensive Walls: Parts of the ancient stone walls still remain intact, showcasing early fortification methods used to protect settlements from invasions.

-

Urban Layout: Built on a long oval-shaped mound, the city’s planning reflects early efforts to balance defense, housing, and public life.

Unfortunately, Sahr-i-Bahlol is more vulnerable than Takht-i-Bahi. Lack of preservation, illegal digging, and neglect have left much of the site at risk, despite its global heritage status.

🗿 Cultural Insights

These twin sites are emblems of the Gandhāra Civilization, which flourished from the 1st to 5th centuries CE across parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan. The Gandhāran school of thought was not just religious—it was also artistic, blending Greek realism with Indian spiritual symbolism in a way that defined early Buddhist iconography.

Spiritual Significance:

-

Takht-i-Bahi was more than just a monastery—it was a center of Buddhist learning and pilgrimage, drawing monks and students from across Asia.

Artistic Legacy:

-

Many of the Buddha statues and reliefs unearthed from the site are now displayed in museums in Peshawar and Lahore, representing some of the finest Gandhāran sculptural art.

⚠️ Conservation Challenges

Takht-i-Bahi:

-

Although the site is largely intact, constant exposure to weather, tourism pressure, and nearby development requires routine conservation and preventive maintenance.

-

Erosion of paths and degradation of stone joints is slowly taking a toll.

Sahr-i-Bahlol:

-

Illegal excavations, lack of fencing, and uncontrolled agricultural activities have caused severe damage.

-

Despite its heritage value, it suffers from neglect and limited funding, needing urgent protective interventions.

UNESCO and the Pakistani Department of Archaeology have initiated documentation and community awareness programs, but long-term conservation requires stronger policy implementation and regional support.

🌍 Why These Sites Still Matter

The Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Sahr-i-Bahlol offer a tangible connection to a period when this region was a global epicenter of knowledge, faith, and cultural synthesis. For heritage enthusiasts, researchers, and spiritual seekers, these sites are a reminder that Pakistan’s historical narrative is both diverse and globally relevant.

Preserving them means protecting a legacy of peaceful coexistence, intellectual growth, and artistic excellence values that the modern world still strives to uphold.

Also See: Historical Places in Pakistan

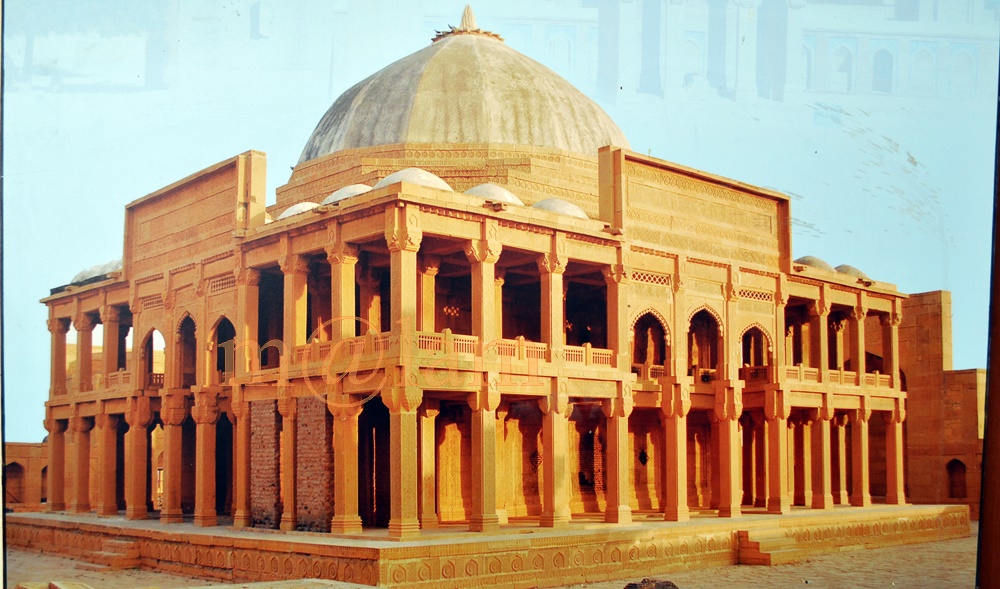

4. 🏛️ Historical Monuments at Makli, Thatta

Picture by: https://eagleeye.com.pk/

Just a short drive from the historic city of Thatta lies Makli Necropolis—a sprawling, silent city of the dead that whispers tales of royalty, saints, poets, mystics, and warriors. As one of the largest funerary sites in the world, Makli is not merely a graveyard—it is an open-air museum chronicling Sindh’s spiritual, political, and architectural journey from the 14th to the 18th century.

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981 under criterion (iii), Makli offers an unparalleled record of Islamic funerary art, blending diverse regional styles into a monumental expression of faith and legacy.

📍 Location and Landscape

-

Province: Sindh, Pakistan

-

Proximity: Approximately 6 kilometers from Thatta city and about 98 kilometers east of Karachi, near the apex of the Indus River Delta.

Covering a massive area of 10 square kilometers, the Makli Necropolis is home to over 500,000 tombs, including those of Sufi saints, rulers of the Samma, Arghun, Tarkhan, and Mughal dynasties, military commanders, and revered scholars.

🏗️ Historical Significance

Makli’s history begins in the 14th century, when the revered Sufi saint Shaikh Jamali chose this serene site for meditation and eventual burial. Over time, local rulers and elites followed suit, turning Makli into a sacred city of remembrance.

For four centuries, Makli evolved into the preferred burial site for Sindh’s elite, making it not only a place of spiritual reverence but also a canvas of dynastic power, artistic innovation, and evolving architectural expression.

🏙️ Architectural Highlights

What makes Makli truly unique is its fusion of architectural styles, incorporating influences from Muslim, Hindu, Persian, Mughal, and Gujarati traditions. This diverse lineage is reflected in its:

-

Intricately carved sandstone and limestone structures

-

Decorative tile work

-

Inscriptions from the Quran

-

Calligraphic panels and floral motifs

Notable Structures:

-

Tomb of Jam Nizamuddin II (1461–1509): A square sandstone tomb displaying floral medallions and geometric patterns with visible Gujarati influence. Interestingly, its dome was never completed, giving it a dramatic, open-air presence.

-

Tomb of Isa Khan Tarkhan I: Built in the late 16th century, this structure features Quranic inscriptions on all inner walls and includes a small chamber housing the graves of five royal women, believed to be Isa Khan’s family members.

-

Tomb of Isa Khan Hussain II Tarkhan: A more elaborate, two-story structure built with dressed stone and adorned with cupolas, balconies, and corner towers, representing a blend of Timurid, Gujarati, and local Sindhi architecture.

🗿 Cultural Insights

Sufi and Spiritual Heritage:

Makli’s earliest development was driven by Sufi mysticism. The initial spiritual significance laid the foundation for its evolution into a royal necropolis, reflecting a balance between religious humility and worldly grandeur.

Artistic Symbolism:

The tombs are adorned with rare iconographic elements—depictions of animals, weaponry, and warriors on horseback, not typically found in Muslim graveyards. Some structures even include lotus flowers, showing Hindu symbolism, and indicating the interfaith and intercultural tolerance that once thrived in the region.

⚠️ Conservation Challenges

Despite its global significance, Makli faces numerous conservation issues:

Environmental Threats:

-

High humidity, temperature fluctuations, and saline winds have led to erosion, discoloration, and cracking of the monuments.

-

The shift in the Indus River’s course has disturbed the local water table, exacerbating salt damage and structural instability.

Human-Induced Risks:

-

Vandalism, unauthorized construction, and grave robberies have severely impacted several key monuments.

-

The sheer size of the necropolis makes monitoring and surveillance extremely difficult.

Preservation Efforts:

-

The Government of Sindh, through its Culture Department, is officially responsible for the site’s upkeep. Some UNESCO-funded programs and academic partnerships have supported documentation and limited conservation efforts.

-

However, funding remains insufficient, and comprehensive restoration strategies are urgently required to save endangered tombs from irreversible collapse.

🌍 Why Makli Still Matters

Makli Necropolis is not just a graveyard—it is a timeless narrative carved in stone, where every tomb tells a story of faith, art, identity, and mortality. It is a rare site where Sufism meets sovereignty, where architecture meets asceticism, and where Sindh’s past continues to echo through silence.

Its preservation is not only about saving history; it’s about honoring the pluralistic legacy of a civilization that once believed beauty belonged even in death.

5. 🏰 Fort and Shalimar Gardens in Lahore

In the cultural heart of Punjab lies a duo of timeless architectural masterpieces—Lahore Fort and the Shalimar Gardens—symbols of the Mughal Empire’s zenith in South Asia. These monuments are a testament to the empire’s pursuit of beauty, precision, and paradise on earth, and together they form one of Pakistan’s most revered UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Inscribed in 1981 under criteria (i), (ii), and (iii), these sites represent the pinnacle of Mughal aesthetics and urban landscaping, showcasing intricate design, balance, and symbolism in every arch, fountain, and facade.

📍 Location

-

Lahore Fort is anchored at the northern end of Lahore’s Walled City, directly facing the majestic Badshahi Mosque.

-

Shalimar Gardens: Located roughly 8 kilometers east of the Fort, in the historic Baghbanpura neighborhood, just off the GT Road.

This spatial separation symbolizes the Mughal ideology—power within the walls of the fort, and paradise outside them.

🏗️ Historical Significance

Lahore Fort:

While its origins trace back to at least the 11th century, the Lahore Fort reached its peak during the Mughal period, especially under Emperor Akbar (ruled 1556–1605). Later emperors—including Jehangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb—continued expanding and embellishing it, transforming the citadel into a showcase of military strength and artistic finesse.

Shalimar Gardens:

Built between 1641–1642 by Emperor Shah Jahan, the same emperor behind the Taj Mahal, the Shalimar Gardens embody the Charbagh (four-part) layout inspired by Persian gardens, meant to represent Jannat, or Paradise, on earth.

🏯 Lahore Fort: Architectural Highlights

The fort spans over 20 hectares, housing a complex of palaces, halls, mosques, and gardens, each reflecting a blend of Persian, Central Asian, and indigenous South Asian influences.

-

Alamgiri Gate: Built by Aurangzeb in 1673, this monumental gate served as the ceremonial royal entrance, facing the Badshahi Mosque.

-

Sheesh Mahal (Palace of Mirrors): Constructed under Shah Jahan, this exquisite white marble pavilion is decorated with intricate mirror work (ayina kari) and semi-precious inlays—a true masterpiece of Mughal opulence.

-

Naulakha Pavilion: Named for its construction cost—nine lakh rupees—it features a distinctive curved roof and serves as a symbol of imperial luxury.

-

Diwan-i-Aam & Diwan-i-Khas: The public and private audience halls used for political and state affairs, showcasing carved columns, painted ceilings, and floral motifs.

-

The Picture Wall: A stunning 450-meter-long mural, adorned with tile mosaics, frescoes, calligraphy, and geometric patterns—a visual chronicle of the Mughal court.

🌺 Shalimar Gardens: Design and Features

The Shalimar Gardens are a paradise terraced into three levels, each with a distinct social purpose:

-

Farah Baksh (Bestower of Pleasure): Reserved for the emperor and his family.

-

Faiz Baksh (Bestower of Goodness): For nobles and courtiers.

-

Hayat Baksh (Bestower of Life): Open to the public on special occasions.

Water Engineering:

The gardens originally featured a sophisticated hydraulic system powering 410 fountains across all three terraces. Five water cascades, including the grand marble cascade and Sawan Bhadun, brought the garden to life, blending sound, motion, and cooling microclimates to heighten sensory pleasure.

Structures Within:

-

Sawan Bhadun Pavilions

-

Naqar Khana (Drum House)

-

Hammam (Royal Bath)

-

Baradaries: Open-sided, columned pavilions for rest and leisure

Each structure was strategically placed to align with views, water channels, and sunlight, creating a choreographed experience of visual and spiritual harmony.

🗿 Cultural Insights

The Lahore Fort and Shalimar Gardens represent the culmination of Mughal artistic ambition—not just as centers of governance and leisure, but as philosophical spaces designed to manifest the ideal Islamic city and garden.

Mughal Aesthetic Ideals:

-

Geometry = divine order

-

Water = purity and paradise

-

Architecture = power and perfection

Historical Role:

-

The gardens once hosted the Mela Chiraghan (Festival of Lights), honoring Sufi saint Shah Hussain—an event that attracted mystics, poets, and musicians from across the region.

⚠️ Conservation Challenges

Both sites have battled natural decay, urban sprawl, and policy neglect for decades.

Main Threats:

-

Pollution and acid rain are damaging stone and tile work.

-

Urban encroachment around Shalimar Gardens is affecting original views and buffer zones.

-

Humidity and rainfall accelerate erosion and deterioration.

Restoration Efforts:

-

Major restorations of the Sheesh Mahal, Picture Wall, and hydraulic fountains have been completed with assistance from UNESCO, the Walled City of Lahore Authority, and international partners.

-

The site was placed on UNESCO’s List of Endangered Sites in 2000, but successful interventions led to its removal from the list in 2012.

🌍 Why These Sites Still Matter

The Fort and Shalimar Gardens in Lahore are more than architectural relics—they are statements of an era that balanced power with poetry, ambition with artistry. They remind us that cities, when built with beauty and meaning, can endure centuries and still move us today.

In preserving these sites, we not only protect our heritage but also celebrate the vision, imagination, and cultural genius of the Mughal Empire.

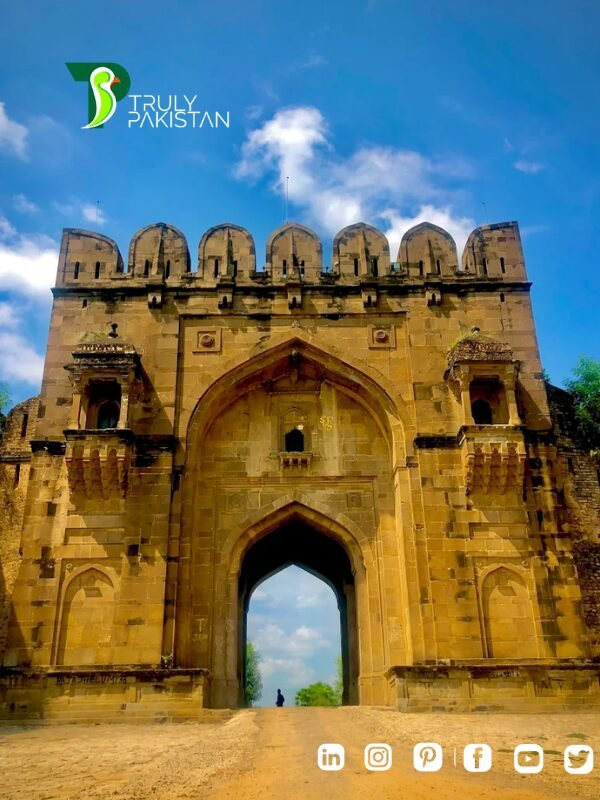

6. 🏰 Rohtas Fort: A Testament to 16th-Century Military Architecture

Standing tall over the Potohar Plateau in Punjab, Rohtas Fort is one of South Asia’s most formidable examples of pre-Mughal military architecture. Built not for aesthetic delight but for strategic dominance, this colossal fortress was designed to be impenetrable—and it lived up to that goal, never falling to an enemy in battle.

In 1997, Rohtas Fort was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site under criteria (ii) and (iv), honoring its architectural innovation and historical importance in South and Central Asia.

📍 Location

-

Province: Punjab, Pakistan

-

Proximity: Approximately 16 kilometers northwest of Jhelum city, near the town of Dina, situated strategically along the historic Grand Trunk Road—the ancient artery connecting Afghanistan’s highlands to the fertile plains of the subcontinent.

Its location was no accident; it served as a military checkpoint controlling access between the mountainous northern regions and the rest of the empire.

🏗️ Historical Significance

Rohtas Fort was commissioned in 1541 CE by Sher Shah Suri, founder of the Sur Empire, shortly after his triumph over the exiled Mughal emperor Humayun. Its construction continued until 1548 CE.

Primary Purposes:

-

To suppress the rebellious Gakhar tribes who supported Humayun.

-

To block Humayun’s return from Persia and secure Sher Shah’s control of the northern frontiers.

Unlike other Mughal-era forts known for their opulence, Rohtas was designed for war—with walls, bastions, and gates focused entirely on defense and deterrence.

🛡️ Architectural Highlights

Spanning over 70 hectares (170 acres), Rohtas Fort combines strategic design with brutal functionality, establishing it as a model for later Mughal military structures.

Walls & Layout:

-

The fort is surrounded by thick masonry walls, 10 to 18 meters high and up to 13 meters thick, strengthened by 68 semi-circular bastions.

-

These walls form a 4-kilometer-long perimeter, enclosing a self-sustained fortress capable of withstanding prolonged sieges.

Monumental Gates:

Rohtas Fort features 12 gates, each with unique strategic and symbolic roles.

-

Sohail Gate: The ceremonial main entrance, notable for its elaborate ashlar stonework and royal grandeur.

-

Kabuli Gate: Facing Kabul, this gate now houses a visitor center and small museum, preserving artifacts and stories from the fort’s past.

-

Shah Chandwali Gate: Named after a revered local saint, this gate features double-arched design, enhancing its defensive capability.

Machicolations & Merlons:

Above many gates and walls, defensive features such as machicolations (stone openings used to drop boiling oil or stones) and merlons (parapet gaps for archers) provide insight into the fort’s military focus.

Water Management:

The fort contains three baolis (stepped wells), enabling residents to maintain an independent water supply during times of siege.

🕌 Interior Structures:

-

Shahi Masjid: A modest mosque near the Kabuli Gate, constructed in early Islamic style with three domes and a simple prayer hall.

-

Haveli Man Singh: A small palace or residence attributed to Raja Man Singh, added during the later Mughal period, showcasing Hindu Rajput architectural influences, such as jharokas and carved balconies.

🗿 Cultural and Historical Insights

Architectural Fusion:

Rohtas Fort stands at the crossroads of Turkish, Persian, South Asian, and Afghan military design, blending styles from multiple empires. Its scale and layout would go on to influence Mughal fortifications, including the famed Red Fort in Delhi.

Unconquered Legacy:

Remarkably, Rohtas Fort was never breached by force. Its sheer scale, high vantage, and robust engineering made it an unshakeable stronghold, preserving its structure over centuries.

Adaptive Use Over Time:

The fort remained operational under multiple empires—from the Mughals to the Durranis, then the Sikh Empire, and finally the British, serving both military and administrative purposes.

⚠️ Conservation and Current Status

Protected Monument:

-

Rohtas Fort was first declared a protected monument in 1919 during the British Raj.

-

It is currently managed by the Directorate General of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Punjab.

Key Challenges:

-

Weathering and erosion, particularly from rainwater.

-

Encroachments and livestock grazing damage the walls and interior structures.

-

Inadequate maintenance and lack of awareness, particularly in rural outreach and tourism promotion.

Preservation Efforts:

-

Some conservation projects have been funded by the Norwegian and German governments, alongside local initiatives.

-

Signage, fencing, and site interpretation have improved, but more is needed to protect Rohtas for future generations.

🌍 Why Rohtas Fort Still Matters

Rohtas Fort is a monument to power, resilience, and strategy. It reflects the political chaos of the 16th century, the ambition of Sher Shah Suri, and the fortification traditions that would shape the subcontinent’s architectural legacy.

Its survival—unconquered and largely intact—is a rare feat in the tumultuous history of South Asia. Visiting Rohtas is not just an encounter with stone walls, but with a story of empire, defense, and enduring legacy.

🌍 Preserving the Past, Shaping the Future

The six UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Pakistan featured above are more than just architectural wonders or tourist destinations—they are living legacies of civilizations that once shaped the intellectual, spiritual, and cultural fabric of the world.

Each site holds a unique place in history:

-

Mohenjo-Daro speaks of urban genius long before modern cities were born.

-

Taxila stands as a symbol of ancient academic excellence.

-

Takht-i-Bahi and Sahr-i-Bahlol echo the spiritual devotion of Buddhist monastic life.

-

Makli reflects the artistic and spiritual evolution of Sindh.

-

Lahore Fort and Shalimar Gardens celebrate Mughal grandeur and garden design.

-

Rohtas Fort reminds us of strategic brilliance in military planning.

As we look to the future, preserving these landmarks isn’t just about safeguarding stones and symbols—it’s about protecting the cultural identity and historical consciousness of generations to come. Let these stories inspire not only awe but also responsibility—to travel with respect, to advocate for heritage conservation, and to understand that history, when protected, always gives back.

📚 Resources & References

-

Archaeological Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro

-

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Moenjodaro

-

Wikipedia. Mohenjo-daro

-

Pakistan Heritage Portal. Mohenjo-Daro Archaeology

-

-

Taxila: A Crossroads of Civilizations

-

Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Sahr-i-Bahlol

-

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Takht-i-Bahi and Sahr-i-Bahlol

-

Wikipedia. Takht-i-Bahi

-

Department of Archaeology, Pakistan

-

-

Historical Monuments at Makli, Thatta

-

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Makli Necropolis

-

Wikipedia. Makli Necropolis

-

Dawn News Archive. Makli Graveyard Features

-

-

Fort and Shalimar Gardens in Lahore

-

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Lahore Fort and Shalimar Gardens

-

Wikipedia. Lahore Fort, Shalimar Gardens

-

Walled City of Lahore Authority. Official Portal

-

-

Rohtas Fort

-

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Rohtas Fort

-

Wikipedia. Rohtas Fort

-

Directorate General of Archaeology, Government of Punjab

-