The Roof of the World — Pakistan’s 7000 Meter Mountains

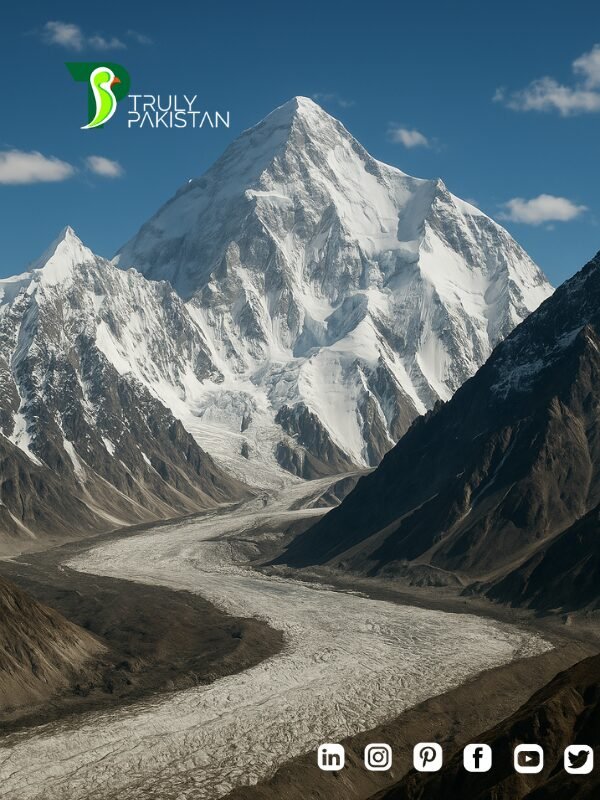

At the intersection of colossal mountain systems, Pakistan occupies one of the most extraordinary positions in global geography. Home to some of the highest, most formidable peaks on Earth, Pakistan serves as a natural convergence point for the Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir ranges — three of the world’s great uplifted zones formed by the ongoing collision between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. This rare geographical overlap makes Pakistan one of the most vertically dominant landscapes anywhere on the planet.

While the world often turns its attention to Pakistan’s 8,000-meter giants — K2, Nanga Parbat, Broad Peak, and the Gasherbrums — what remains equally impressive, yet less publicized, is Pakistan’s remarkable collection of mountains rising above 7,000 meters. These peaks represent a critical middle tier in high-altitude mountaineering, offering both extreme technical challenges and remarkable diversity in terrain, route difficulty, and accessibility.

The concentration of 7,000-meter peaks in Pakistan is unparalleled outside the Himalayas. From the snow-laden mass of Rakaposhi and the golden slopes of Spantik to the severe technical faces of Ultar Sar and Baintha Brakk (The Ogre), these mountains attract climbers seeking serious altitude, researchers investigating geology and climate change, and adventure travelers who want to witness the raw, unfiltered drama of vertical wilderness.

In this guide, we’ll explore Pakistan’s complete collection of 7,000-meter mountains. You’ll discover detailed profiles of each peak, their historical ascents, geographical settings, climbing challenges, and the reasons why Pakistan remains a global epicenter for high-altitude exploration. Whether you’re planning an expedition, researching the region, or simply fascinated by these towering natural monuments, this comprehensive guide offers an in-depth journey into Pakistan’s most awe-inspiring vertical frontiers.

Understanding Pakistan’s High-Altitude Geography

Pakistan sits at the heart of one of the world’s most dramatic tectonic collision zones, where the Indian Plate presses northward into the Eurasian Plate, giving rise to towering mountain systems that continue to rise even today. This ongoing tectonic activity has created some of the most spectacular and densely clustered high-altitude landscapes on Earth. Three major mountain systems converge here — the Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir ranges — making Pakistan a true global epicenter for mountaineering, geology, and climate research.

The Karakoram Range

The Karakoram is the crown jewel of Pakistan’s mountains. Stretching across Gilgit-Baltistan into China and India, the Karakoram boasts the highest concentration of 7,000-meter peaks outside of the main Himalayan chain. Among its most famous giants are K2 (8,611m), the world’s second-highest peak, along with dozens of 7,000-meter summits such as Gasherbrum IV (7,925m), Masherbrum (7,821m), and Chogolisa (7,665m). The Karakoram is renowned for its extreme vertical relief, massive glaciers like the Baltoro and Biafo, and some of the world’s most technically demanding ascents.

The Hindu Kush Range

West of the Karakoram lies the rugged Hindu Kush, extending into Afghanistan. While most of its highest peaks sit outside Pakistan, a significant section falls within the country’s borders, particularly in Chitral and Gilgit. The Hindu Kush adds to Pakistan’s rich 7,000-meter portfolio with peaks such as Noshaq (7,492m) near the Afghan border. This range is known for its steep, sharp profiles and highly technical climbing routes.

The Pamir Knot

In Pakistan’s far northern corridor near the Wakhan Corridor and the Khunjerab Pass, the Pamir Mountains briefly extend into the region. Although the majority of Pamir peaks lie within Tajikistan and China, Pakistan shares proximity to this complex mountain knot, most notably via Muztagh Ata (7,546m) — known as the “Father of Ice Mountains” — which sits just across the border but remains a key part of regional climbing itineraries.

Geological History and Clustering of 7,000 Meter Peaks

The ongoing uplift of these mountains is driven by tectonic collision that began roughly 50 million years ago and continues to shape the landscape today. The Karakoram and Hindu Kush are among the youngest yet most active mountain ranges on Earth, with some of the fastest recorded uplift rates. This geologic youth explains the steep relief, unstable rock formations, active faulting, and the extraordinary clustering of high peaks, particularly the density of 7,000-meter summits packed into relatively small geographic areas.

Unlike the Himalayas, where high peaks are more evenly distributed, Pakistan’s 7,000-meter mountains often rise dramatically within tight corridors, creating towering vertical reliefs of 4,000 to 5,000 meters from the valley floor to the summit. This clustering not only shapes the technical difficulty of these mountains but also contributes to the region’s intense glacial systems and highly dynamic environmental conditions.

Global Importance of Mountaineering and Scientific Research

Pakistan’s 7,000-meter mountains hold global significance far beyond mountaineering. The region provides critical insights into:

-

Plate tectonics and mountain-building processes

-

Glaciology and climate change impacts on some of the largest non-polar glaciers

-

High-altitude human adaptation and physiology

-

Rare biodiversity and alpine ecosystems

-

Meteorological studies due to their influence on regional weather patterns

For climbers, these peaks offer some of the world’s most pristine, demanding, and rewarding challenges, many of which remain far less commercialized than their Himalayan counterparts. For scientists, they offer a living laboratory that continues to evolve with every seismic movement and seasonal glacier shift.

Complete List of 7000 Meter Mountains in Pakistan

| Peak | Height (m) | Range | Key Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rakaposhi | 7,788 | Rakaposhi-Haramosh | Dumani – Mother of Mist |

| Spantik (Golden Peak) | 7,027 | Spantik-Sosbun | Ideal training peak |

| Diran Peak | 7,266 | Between Rakaposhi & Haramosh | Avalanche-prone beauty |

| Ultar Sar | 7,388 | Batura Muztagh | Towering above Hunza |

| Haramosh | 7,409 | Haramosh Subrange | One of the steepest giants |

| Passu Sar | 7,478 | Batura Muztagh | Remote and technical |

| Muztagh Ata | 7,546 | Pamir Extension | Father of Ice Mountain |

| Baltistan Peak (K6) | 7,281 | Masherbrum Mountains | Difficult mixed climb |

| Baintha Brakk (The Ogre) | 7,285 | Panmah Muztagh | Legendary difficulty |

| Chogolisa | 7,665 | Baltoro Muztagh | Bride Peak near Concordia |

| Masherbrum (K1) | 7,821 | Masherbrum Range | The first “K” peak is named |

| Gasherbrum IV | 7,925 | Baltoro Muztagh | One of the most technical |

| Distaghil Sar | 7,885 | Hispar Muztagh | Highest in Hispar |

| Kunyang Chhish | 7,852 | Hispar Muztagh | Challenging ascent |

| Batura I | 7,795 | Batura Muztagh | Western Karakoram |

| Kanjut Sar | 7,790 | Hispar Muztagh | Rarely climbed |

| Pumari Chhish | 7,492 | Hispar Muztagh | Among the steepest |

Rakaposhi (7,788m): The Iconic Pyramid of the Karakoram

Picture by: https://visitinpakistan.com

Location: Nagar Valley, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

Meaning: Dumani — “Mother of Mist” (Burushaski language)

First Ascent: 1958 British-Pakistani expedition led by Mike Banks and Tom Patey

Overview

Rakaposhi is one of Pakistan’s most visually striking mountains and a true jewel of the Karakoram Range. Rising to 7,788 meters (25,551 feet), it ranks as the 27th highest mountain in the world, but its significance goes far beyond mere altitude. What makes Rakaposhi truly exceptional is its sheer rise from the surrounding valleys — an uninterrupted vertical gain of nearly 6,000 meters from base to summit, making it one of the world’s most dramatic elevation differences. Few mountains globally exhibit such a steep vertical face within such a short horizontal distance.

Positioned near the Karakoram Highway, Rakaposhi is one of the few major Himalayan or Karakoram peaks easily visible from a paved road, making it highly accessible for trekkers, tourists, and photographers who wish to witness its grandeur without committing to a full expedition. It dominates the skyline of both Nagar and Hunza Valleys, standing as a constant presence for local communities who refer to it affectionately as Dumani — “Mother of Mist” — due to the circular bands of clouds that frequently wrap around its summit.

Geographical Setting

Rakaposhi forms part of the Rakaposhi-Haramosh subrange of the greater Karakoram system, located just south of the Hunza River in Gilgit-Baltistan. The surrounding landscape is rich with natural beauty: lush green valleys, glaciers, moraines, and diverse alpine flora and fauna. Rakaposhi Glacier and Minapin Glacier descend from its flanks, feeding local water systems and sustaining life in the valleys below.

Its prominent location and relative accessibility have made Rakaposhi a popular trekking destination, especially the trek to Rakaposhi Base Camp (around 3,500 meters), which offers magnificent views of the north face without requiring technical climbing.

First Ascent & Climbing History

Despite its inviting appearance, Rakaposhi remained unclimbed until 1958 due to its technical challenges and severe objective hazards, including seracs, crevasses, and avalanches. The first successful ascent was made on June 25, 1958, by a joint British-Pakistani expedition led by Mike Banks and Tom Patey. The team climbed via the southwest ridge, which remains the standard route even today.

The ascent was not without difficulty — Mike Banks famously suffered severe frostbite during the summit push, yet both climbers managed to return safely after spending an open bivouac at over 7,000 meters.

Since then, various expeditions have attempted alternative routes, including the formidable north face, but few have succeeded. Rakaposhi has developed a reputation for being a deceptively dangerous mountain due to its constant exposure to avalanches, rapid weather changes, and its extensive glaciated terrain.

Technical Climbing Characteristics

-

Altitude: 7,788 meters (25,551 ft)

-

Vertical Relief: ~5,900 meters from the Hunza-Nagar Valley floor

-

Standard Route: Southwest Ridge via Minapin Glacier

-

Difficulty: Alpine PD to AD (depending on conditions)

-

Major Risks: Avalanches, unstable snowfields, rockfall, crevasses

-

Season: June to early August (best weather window)

-

Duration: Typical expeditions run 30-40 days, including acclimatization

Although Rakaposhi is technically less complex than nearby Karakoram giants like K2 or Gasherbrum IV, its massive size, severe altitude, and unstable conditions make it a serious undertaking even for experienced climbers. Very few commercial guiding services operate on Rakaposhi compared to 8000-meter peaks, and most ascents are still conducted by small, independent expeditions.

Cultural and Scientific Importance

For local communities, Rakaposhi holds cultural significance as a sacred natural monument. In the Burushaski and Shina languages, it symbolizes purity, motherhood, and spiritual protection. The mountain also serves as a critical research site for scientists studying:

-

Glacial retreat and climate change

-

High-altitude ecology and plant biodiversity

-

Water resources feeding the Indus River system

-

Geomorphological studies on rapid mountain building

Rakaposhi’s glaciology contributes directly to regional water supplies, and its changing ice mass is a key climate indicator for South and Central Asia.

Notable Fact

-

Rakaposhi holds the world record for the greatest continuous elevation rise on Earth within 20 kilometers horizontal distance — a vertical wall unmatched even by Everest or K2 in sheer relief.

Spantik (7,027m): The Golden Gateway to High-Altitude Mountaineering

Location: Nagar Valley, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

Also Known As: Golden Peak

First Ascent: 1955 by a German expedition led by Karl Kramer

Overview

Among Pakistan’s many towering giants, Spantik (7,027m) holds a special place as one of the most accessible and climber-friendly 7,000-meter peaks. Its elegant pyramid shape, gently sweeping ridges, and shimmering golden hues during sunrise and sunset have earned it the nickname “Golden Peak.” Located in the Nagar Valley of Gilgit-Baltistan, Spantik sits between the Hunza and Indus valleys, commanding panoramic views of surrounding Karakoram giants like Rakaposhi, Diran, and Malubiting.

While many of Pakistan’s high-altitude peaks are known for extreme technical difficulty, Spantik offers a rare combination: substantial altitude combined with a comparatively straightforward climbing route. This balance makes it one of the most popular training peaks for climbers preparing for higher 8,000-meter ascents such as Gasherbrum II, Broad Peak, or even K2.

Geographical Setting

Spantik lies within the Spantik-Sosbun subrange of the Karakoram and is approached primarily through the Nagar Valley. Its flanks are fed by several glaciers, including the Chogolungma Glacier on the south and the Malubiting Glacier to the north. These glacial systems form part of the region’s rich water resources and high-altitude ecosystems.

Despite its imposing appearance, the south-east ridge — the standard climbing route — provides a relatively non-technical but physically demanding approach to the summit. This route is popular among guided commercial expeditions, local Pakistani operators, and independent mountaineers seeking their first venture into extreme altitude.

First Ascent & Climbing History

The first successful ascent of Spantik was made in 1955 by a German expedition led by Karl Kramer. They approached the mountain via the south-east ridge, which remains the most frequently used route to this day. Since then, Spantik has seen a steady flow of ascents, especially after Pakistan’s climbing industry began offering guided expeditions in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Unlike some Karakoram peaks where successful ascents remain rare, Spantik now hosts multiple expeditions every season, contributing to the growing training culture of Pakistan’s domestic and international climbing community.

Why Spantik is Ideal for First-Time 7,000m Climbers

-

Gradual acclimatization profile: The south-east ridge allows climbers to adapt to high altitude progressively.

-

Low technical difficulty: Requires basic snow and ice climbing skills without extreme vertical sections.

-

Minimal objective hazards: Lower risk of avalanches, rockfall, and crevasses compared to many Karakoram neighbors.

-

Stable weather window: Climbing season from late June to mid-August offers the most stable conditions.

-

Logistical ease: Base camp is accessible via jeep road to Arandu village, followed by a relatively short trek.

-

Training ground for higher goals: Many climbers use Spantik to gain essential 7,000m experience before tackling Pakistan’s 8,000m giants.

Technical Climbing Characteristics

-

Altitude: 7,027 meters (23,054 ft)

-

Standard Route: Southeast Ridge

-

Difficulty: Alpine PD to PD+ (moderate snow and ice climbing)

-

Major Risks: Altitude sickness, weather changes, glacier navigation

-

Typical Duration: 20–25 days (including acclimatization)

Cultural & Scientific Significance

While not as culturally sacred as Rakaposhi, Spantik contributes to the local economy by sustaining adventure tourism, supporting dozens of guides, porters, and expedition staff every season. Its relatively safer conditions have made it one of the few Karakoram peaks widely promoted to international amateur climbers seeking their first true Himalayan high-altitude experience.

For researchers, Spantik and its glacier systems also contribute to ongoing studies on glacial melt, regional hydrology, and climate change impact within the Karakoram anomaly — a localized phenomenon where some glaciers appear stable or even growing despite global warming.

Notable Fact

-

From Spantik’s summit, climbers are treated to panoramic views of dozens of Karakoram giants, including Nanga Parbat to the south and the jagged spires of Ultar Sar to the north, making it one of the most photogenic summits in Pakistan.

Diran Peak (7,266m): The Deceptive Beauty of the Karakoram

Location: Between Rakaposhi and Haramosh Massif, Nagar Valley, Gilgit-Baltistan

First Ascent: 1968 Austrian expedition led by Rainer Goeschl, Rudolph Pischinger, and Hanns Schell

Known For: Avalanche risks and deceptive climbing conditions

Overview

Often referred to as one of the most beautiful yet deceptive mountains of the Karakoram, Diran Peak (7,266m) sits quietly overshadowed by its far more famous neighbor, Rakaposhi. However, for climbers who set their eyes on Diran, the challenge is far more treacherous than its smooth, snow-covered dome suggests. Its clean pyramid shape and accessible location make it look approachable, but beneath its graceful appearance lie serious risks, primarily due to unstable snowfields and frequent avalanches.

Diran Peak is part of the Rakaposhi-Haramosh subrange, nestled at the intersection of two major valleys — the Hunza Valley to the north and the Bagrot Valley to the south. Its prominence dominates the skyline above the village of Minapin, drawing trekkers and photographers who often visit Rakaposhi Base Camp and catch stunning views of Diran’s polished snow slopes.

Geographical Setting

Diran is positioned directly east of Rakaposhi and west of Malubiting (7,458m), acting as a smaller but highly visible landmark in the region. Several glaciers, including Minapin Glacier and Barpu Glacier, originate from its slopes. The Minapin Valley serves as the primary access route for most expeditions and trekkers, offering one of the easier approaches to a 7,000-meter base camp in Pakistan.

Despite its relatively straightforward logistics, the climbing risks lie not in technical rock or ice, but in snow stability and rapid weather changes, which have earned Diran a reputation as a dangerous mountain for those who underestimate its hazards.

First Ascent & Climbing History

The first successful ascent of Diran was made in 1968 by an Austrian expedition led by Rainer Goeschl, Rudolph Pischinger, and Hanns Schell via the northwest ridge — still considered the standard route today.

However, multiple earlier attempts prior to 1968 were thwarted due to extreme snow conditions, unexpected storms, and fatal accidents. Several expeditions have faced tragedy due to the peak’s heavy snow accumulation, unstable cornices, and the risk of slab avalanches that can sweep climbers off the mountain during summit pushes.

Even after its first ascent, Diran has remained relatively less climbed compared to other 7,000m peaks like Spantik or Ultar Sar due to its high objective danger despite its moderate technical difficulty.

Technical Climbing Characteristics

-

Altitude: 7,266 meters (23,839 ft)

-

Standard Route: Northwest Ridge via Minapin Glacier

-

Difficulty: Alpine PD (technically moderate, but physically demanding)

-

Major Risks: Avalanche-prone slopes, unstable snowfields, whiteout conditions, hidden crevasses

-

Typical Expedition Duration: 20–25 days

-

Climbing Season: Mid-June to early August offers the safest window with relatively stable snow conditions

The key challenge of Diran lies not in steep technical faces but in navigating vast, exposed snowfields where even minor weather shifts can destabilize entire slope sections. Successful ascents require precise timing, early summit pushes, and close attention to snowpack behavior.

Why Diran is Popular Yet Dangerous

-

Visually inviting: Its symmetrical snow dome attracts many amateur climbers.

-

Non-technical climbing: No extreme rock climbing or icefall navigation.

-

Hidden hazards: Highly unpredictable avalanche conditions make it treacherous.

-

Fewer commercial expeditions: Unlike Spantik or Rakaposhi, Diran remains reserved for climbers with advanced knowledge of avalanche safety and glacial travel.

Many local guides in Nagar refer to Diran as “the mountain that tests patience”, as weather delays, sudden snow dumps, and fragile snow bridges often force teams to abandon summit bids even after weeks of preparation.

Scientific Significance

Diran’s snowfields and glaciers play an important role in regional hydrology, feeding into the Hunza and Indus river systems. Like many Karakoram peaks, Diran contributes valuable data to ongoing research into:

-

Glacial mass balance

-

Snow avalanche behavior

-

Regional climate change and the Karakoram anomaly

Notable Fact

-

Diran Peak is one of the few 7,000-meter peaks visible from the Karakoram Highway, and its summit frequently appears glowing pink at sunrise, making it one of the most photographed lesser-known giants in Pakistan.

Ultar Sar (7,388m): The Towering Wall Above Hunza

Location: Above Hunza Valley, Batura Muztagh subrange, Karakoram, Gilgit-Baltistan

First Ascent: 1996 Pakistani expedition (Qadri and his team, Alpine Club of Pakistan)

Technical Difficulty: Exceptionally high — one of Pakistan’s most technically demanding 7,000m peaks

Overview

Ultar Sar (7,388m) is one of the most visually dramatic and technically severe mountains in the Karakoram. Towering directly above the famous Hunza Valley and the historic town of Karimabad, Ultar Sar dominates the skyline with its razor-sharp ridges, steep rock faces, and intimidating vertical rise. Its sheer prominence makes it look like a vertical wall of rock and ice shooting straight up from the valley floor, offering a near-unmatched elevation gain of approximately 5,300 meters over just 10 kilometers of horizontal distance — one of the greatest local reliefs anywhere in the world.

Despite being visible from one of Pakistan’s most visited regions, Ultar Sar is far from being a common climbing destination due to its extreme technical challenges, complex weather, unstable rock faces, and severe avalanche risk.

Geographical Setting

Ultar Sar is part of the westernmost Batura Muztagh, a subrange of the Karakoram, sitting just northwest of Hunza’s main town of Karimabad. Its proximity to civilization contrasts sharply with its climbing difficulty. On clear days, Ultar Sar’s towering spires are easily visible to tourists standing at the Baltit Fort or Eagle’s Nest, adding to Hunza Valley’s legendary panoramic beauty.

The mountain is flanked by several large glaciers, including the Ultar Glacier to the east and the Ghulkin Glacier nearby. These glaciers feed critical water systems supporting life throughout the Hunza region.

First Ascent & Climbing History

Ultar Sar remained unclimbed far longer than many higher Karakoram peaks due to its lethal combination of vertical relief, loose rock, icefalls, and extremely exposed faces.

The first successful ascent was achieved in 1996 by a Pakistani team led by Wajidullah Nagri and Akhbar Qadri under the Alpine Club of Pakistan. Their historic climb marked a major milestone in Pakistani mountaineering history as local climbers successfully summited one of their country’s most formidable peaks.

Prior to this, multiple expeditions from Japan, the UK, and Europe attempted the peak in the late 1980s and early 1990s but were turned back due to frequent avalanches, serac collapses, and technical obstacles that prevented teams from gaining the upper ridges.

Even after the 1996 ascent, very few successful summits have been recorded due to the mountain’s extreme objective dangers and unstable conditions. As of today, Ultar Sar remains one of the least-climbed 7,000-meter peaks in Pakistan.

Technical Climbing Characteristics

-

Altitude: 7,388 meters (24,239 ft)

-

Standard Route: Southeast Ridge and variations

-

Difficulty: ED (extremely difficult) — steep technical mixed climbing (rock, snow, ice)

-

Major Risks: Rockfall, unstable seracs, heavy avalanche zones, rapidly changing weather

-

Typical Expedition Duration: 30–40 days

-

Best Climbing Window: June to early August

Ultar Sar demands extremely high levels of technical competence in both alpine rock and ice climbing, expert navigation, and high-altitude endurance. Few commercial expeditions attempt this peak, and only highly experienced mountaineering teams typically make serious summit bids.

Why Ultar Sar is Technically Unique

-

Unstable geology: Loose rock and steep ice cliffs require constant caution.

-

Severe avalanche zones: Sudden weather changes destabilize entire snowfields.

-

Sharp, narrow ridgelines: Knife-edge ridges test climbers’ balance, stamina, and route-finding ability.

-

Proximity to Hunza: Unlike most remote Karakoram peaks, Ultar Sar’s immediate proximity to inhabited valleys makes its looming vertical relief even more impressive.

Scientific and Environmental Importance

Ultar Sar contributes to ongoing studies on:

-

Landslide activity and unstable slope dynamics in rapidly rising mountains

-

Glacial retreat behavior in localized Karakoram microclimates

-

Seismic activity linked to the region’s tectonic youth

Its glacial meltwater supports agricultural and drinking water for several communities in central Hunza.

Notable Fact

-

Ultar Sar was once mistakenly believed to be the highest unclimbed peak in the world during the late 1980s until the successful 1996 Pakistani ascent.

Haramosh Peak (7,409m): The Silent Giant of the Karakoram

Location: Haramosh Range, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

Known For: Steep vertical rise, high fatality rate in early expeditions, and technical and dangerous terrain

Overview

Haramosh Peak (7,409m) is one of the lesser-known but most formidable 7,000-meter peaks in the Karakoram. Sitting southeast of Rakaposhi, Haramosh is part of the smaller Haramosh subrange, which branches off from the main Karakoram chain. Unlike many of its more famous neighbors, Haramosh remains largely isolated, less commercialized, and far more challenging to climb.

What makes Haramosh particularly dramatic is its incredible vertical relief: it rises nearly 5,000 meters directly above the Indus River Valley within a horizontal distance of just 10 to 12 kilometers. This combination of steep rock faces, glaciated slopes, unstable snowfields, and severe weather patterns makes Haramosh an intimidating objective for even the most seasoned mountaineers.

Geographical Setting

Haramosh Peak dominates the skyline above the Indus and Gilgit Rivers, standing northeast of the town of Skardu and southeast of Gilgit city. The approach to the mountain typically begins from the Haramosh Jutial Valley, accessed via a long and challenging trek that takes climbers deep into a remote region of the Karakoram.

The mountain is bordered by glaciers such as Kutia Lungma Glacier and Chogo Lungma Glacier, which feed into the regional water system and play a vital role in the Indus Basin’s glacial hydrology.

Early Expeditions & Fatal Climbing History

Haramosh Peak earned a grim reputation early in its climbing history due to multiple fatal incidents.

The mountain was first successfully climbed in 1958 by an Austrian expedition led by Heinrich Roiss, Stefan Pauer, and Franz Mandl via the Southwest Face.

However, its notoriety stems largely from a tragic British expedition in 1957 (one year prior), where two members of the team — Tony Streather and Bernard Jillot — suffered a disastrous fall and prolonged exposure during their descent, leading to one fatality and near-death situations for survivors. The harrowing survival story is still remembered as one of the most dramatic tales in Karakoram climbing history and remains a cautionary lesson on Haramosh’s extreme objective dangers.

Since these early ascents, very few expeditions have attempted Haramosh due to its combination of:

-

Severe rockfall zones

-

Unstable snow and ice routes

-

Constant avalanche danger

-

Remote access requires highly self-sufficient teams

As a result, Haramosh remains one of Pakistan’s least-climbed 7,000-meter peaks, despite its relatively lower elevation compared to its Karakoram neighbors.

Technical Climbing Characteristics

-

Altitude: 7,409 meters (24,308 ft)

-

Standard Route: Southwest Face (first ascent route)

-

Difficulty: Alpine D to ED depending on conditions — highly exposed, complex ice/snow/rock climbing

-

Major Risks: Avalanche-prone slopes, unstable snowfields, icefall collapse, extreme storms, technical ridge crossings

-

Typical Expedition Duration: 30–35 days

-

Best Climbing Window: Late June to early August

Climbers attempting Haramosh face highly technical mixed climbing, exposure to falling seracs, and challenging navigation over corniced ridges and steep glacial faces. The mountain requires proficiency in advanced alpine climbing, ice climbing, and high-altitude survival skills.

Why Haramosh Remains So Dangerous

-

Highly remote: Rescue is nearly impossible beyond base camp.

-

Complex weather system: Sudden storms and heavy snowfall destabilize the mountain quickly.

-

Minimal established routes: Few successful ascents mean limited route information.

-

Frequent rockfall and icefall: Continuous slope movement increases objective danger.

Even among veteran Karakoram climbers, Haramosh is often spoken of with great caution and respect.

Scientific Significance

Though less studied than major glaciated zones like Baltoro, Haramosh’s glaciers feed into Pakistan’s greater Indus River system, contributing to:

-

Regional water security

-

Climate change observation (glacier mass balance studies)

-

High-altitude weather pattern research

Because of its steep relief and young geomorphology, Haramosh also provides data on the active tectonic processes still shaping the Karakoram region.

Notable Fact

-

Haramosh Peak is sometimes referred to as one of the “steepest mountains on Earth” relative to its vertical gain from the valley floor to the summit within such a short horizontal distance.

Passu Sar (7,478m): The Hidden Ice Fortress of Gojal

Location: Batura Muztagh subrange, Gojal (Upper Hunza), Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan

First Ascent: 1994 German expedition (Max Wallner, Dirk Naumann, Ralf Lehmann, Volker Wurnig)

Known For: Remote location, extreme technical difficulty, very limited ascents

Overview

Passu Sar (7,478m) is one of the most remote and technically demanding 7,000-meter peaks in the Karakoram. Located in the Batura Muztagh subrange near the village of Passu in Gojal (Upper Hunza), it rises above the famous Passu Glacier, forming part of the distinct skyline that includes the famous Passu Cones (or Tupopdan), which are visible directly from the Karakoram Highway.

Unlike some of its more accessible Karakoram siblings, Passu Sar remains rarely climbed and almost unknown outside of serious high-altitude mountaineering circles. Its highly technical ridges, unstable ice cliffs, and steep glaciated faces make it one of the least commercialized 7,000-meter peaks in Pakistan.

Geographical Setting

Passu Sar lies in the far western end of the Karakoram, just north of the Hunza River, in one of the most stunning high-mountain corridors in Pakistan. The entire Batura Muztagh region, where Passu Sar sits, is known for its complex glacial systems, sheer vertical rock towers, and extremely rugged, isolated terrain.

Approach routes to Passu Sar typically begin from the village of Passu, followed by challenging glacier travel across heavily crevassed ice fields. The Passu and Batura Glaciers feed into the region’s vital water sources, supporting agriculture and settlements in Hunza.

First Ascent & Climbing History

Passu Sar remained unclimbed for decades, not due to a lack of interest, but because of its extreme technical barriers. The first successful ascent came in 1994, when a German team consisting of Max Wallner, Dirk Naumann, Ralf Lehmann, and Volker Wurnig finally reached the summit after an exceptionally difficult climb via the southeast ridge.

Prior to the 1994 success, several expeditions in the 1980s and early 1990s attempted Passu Sar but were turned back by unstable weather, massive serac falls, and highly technical ice walls that presented enormous objective hazards.

Even after the first ascent, very few teams have attempted the mountain, and successful summits remain exceptionally rare due to the peak’s dangerous combination of:

-

Steep technical ridgelines

-

Highly unstable snow conditions

-

Large hanging glaciers are prone to collapse

-

Difficult route finding under constantly shifting glacier features

Passu Sar is often compared to nearby Ultar Sar and Baintha Brakk (The Ogre) for its level of difficulty.

Technical Climbing Characteristics

-

Altitude: 7,478 meters (24,629 ft)

-

Standard Route: Southeast Ridge (first ascent route)

-

Difficulty: Alpine ED (extremely difficult) — highly technical mixed climbing on steep ice, snow, and unstable rock

-

Major Risks: Crevasses, unstable seracs, icefall avalanches, rapidly changing weather systems

-

Typical Expedition Duration: 35–40 days

-

Best Climbing Season: Late June to early August (short weather window)

Unlike many other Karakoram peaks, Passu Sar offers no non-technical lines to the summit. Any attempt requires elite-level proficiency in high-altitude mixed climbing and glacier navigation.

Why Passu Sar Remains Rarely Climbed

-

Extreme technical grade: Far beyond the ability of most commercial expeditions

-

High objective danger: Almost continuous exposure to avalanches and icefall

-

Logistical challenges: Remote access, complex glacier crossings, and few established camps

-

Very limited historical data: Few route descriptions exist, making planning far more complex

Passu Sar represents one of the last truly wild 7,000-meter objectives in Pakistan, demanding the highest levels of preparation, technical ability, and risk management.

Scientific and Environmental Significance

The glaciers surrounding Passu Sar, particularly the Passu Glacier and Batura Glacier, are significant research zones in ongoing climate studies. While many glaciers globally are retreating, sections of the Batura Muztagh demonstrate what scientists call the Karakoram Anomaly — localized zones where some glaciers remain stable or show limited growth despite global warming trends.

The mountain also plays a critical role in:

-

Hydrological studies related to glacier-fed irrigation for Upper Hunza’s villages

-

Glaciology research on dynamic ice movement patterns

-

Seismic studies related to ongoing tectonic uplift

Notable Fact

-

Despite its stunning visibility from the Karakoram Highway, Passu Sar is one of the least climbed major peaks in Pakistan, with fewer than a handful of recorded successful ascents since 1994.

Muztagh Ata (7,546m): The Father of Ice Mountains

Location: Pamir Mountains, Western Xinjiang, China (border region with Pakistan near Khunjerab Pass)

Meaning: Muztagh Ata — “Father of Ice Mountains” (Uyghur language)

Known For: One of the world’s most popular high-altitude ski mountaineering peaks

Overview

Muztagh Ata (7,546m) stands apart from the majority of Pakistan’s Karakoram 7,000-meter peaks due to its unique geographical positioning and exceptional accessibility for high-altitude ski mountaineering. Located just beyond Pakistan’s Khunjerab border in the Pamir range of China’s Xinjiang region, it lies at the intersection of the greater Pamir, Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Kunlun mountain systems. Despite being physically across the border, Muztagh Ata has long been integrated into regional mountaineering itineraries for climbers and ski mountaineers operating out of northern Pakistan.

Unlike the vertical granite spires and highly technical ice faces of the Karakoram, Muztagh Ata presents an entirely different mountaineering profile: a massive, broad, glaciated dome that allows for steady, non-technical ascents. Its wide snowfields, gentle slopes (by Karakoram standards), and consistent gradients have made it one of the most popular destinations in the world for high-altitude ski mountaineering.

Geographical Setting

Muztagh Ata rises prominently near the eastern end of the Karakoram Highway, just northeast of the Khunjerab Pass that connects Gilgit-Baltistan to China’s Xinjiang region. The mountain is often visible along the Karakoram Highway when traveling between Tashkurgan and Kashgar.

While its summit belongs to China, its proximity to the Pakistan border has historically made it a logistical extension for many Pakistan-based mountaineering companies. Many climbers visiting northern Pakistan include Muztagh Ata as part of longer regional expeditions that explore both the Karakoram and Pamir systems.

The mountain sits at the edge of the Taklamakan Desert plateau, creating a stunning visual contrast between arid desert basins and massive glaciated peaks.

First Ascent & Climbing History

The first serious attempts to climb Muztagh Ata began as early as the 1890s, with failed expeditions by Swedish explorer Sven Hedin and later British and Soviet teams. Its first successful ascent was finally made in 1956 by a Soviet-Chinese expedition, marking one of the earliest major ascents in the Pamir region during the Cold War mountaineering era.

Since then, Muztagh Ata has seen hundreds of successful ascents annually, primarily by ski mountaineers and climbers seeking high-altitude experience at relative safety compared to the Karakoram or Himalayas.

Why Muztagh Ata is Popular for Ski Mountaineering

-

Non-technical ascent: Lacks steep ice walls or highly exposed ridgelines.

-

Gentle slope gradients: Ideal for both ascent and descent on skis.

-

Good weather stability: Pamir Plateau’s drier climate offers more predictable windows.

-

Relatively lower objective dangers: Minimal avalanche, serac, or rockfall hazards.

-

Perfect for altitude training: Frequently used by climbers preparing for 8,000-meter expeditions.

Muztagh Ata’s south route follows wide, open snowfields that allow for continuous ski descents of nearly 2,500 vertical meters — one of the longest continuous ski descents in the world.

Technical Climbing Characteristics

-

Altitude: 7,546 meters (24,757 ft)

-

Standard Route: Southwest Ridge (non-technical glacier climb)

-

Difficulty: Alpine PD- to PD (non-technical but physically demanding)

-

Major Risks: Altitude sickness, strong winds, severe cold, crevasse navigation

-

Typical Expedition Duration: 20–25 days

-

Best Climbing Window: Late June to August

Despite its gentle profile, Muztagh Ata’s high altitude demands serious acclimatization. Many climbers who underestimate its altitude often suffer from acute mountain sickness (AMS) or fail to summit due to a lack of preparation.

Scientific Significance

Muztagh Ata and the surrounding Pamir glaciers are key study zones for:

-

High-altitude glacier behavior

-

Paleoclimate records extracted from ice cores

-

Atmospheric circulation patterns in Central Asia

-

Cross-border water resources for the Tarim and Indus basins

Because of its unique plateau position, Muztagh Ata serves as a climate indicator for both Central and South Asian hydrological systems.

Notable Fact

-

Muztagh Ata is often cited as one of the easiest 7,000-meter peaks in the world to climb, making it highly attractive for both novice high-altitude climbers and scientific research expeditions.

Other Prominent 7000 m+ Peaks in Pakistan

Baltistan Peak (K6) — 7,281 m

Baltistan Peak, known as K6, is located in the Masherbrum Mountains of Gilgit‑Baltistan. The first successful ascent was made in 1970 by an Austrian expedition led by Eduard Koblmueller, accompanied by Gerfried Göschl, Rainer Göschl, and team members. K6 rises dramatically above the Chogo Lungma Glacier, featuring highly technical ridgelines, steep ice faces, and dangerous mixed terrain. Despite being overshadowed by Masherbrum and K2, K6 remains a highly respected objective due to its dangerous cornices, unstable rock towers, and avalanche-prone flanks. The South Face remains unclimbed, and only a few successful ascents have been recorded via the northeast ridge.

Baintha Brakk (The Ogre) — 7,285 m

Baintha Brakk, more famously known as The Ogre, stands in the Panmah Muztagh subrange of the Karakoram. The first ascent was completed on July 13, 1977, by the legendary British climbers Doug Scott and Chris Bonington, supported by Nick Estcourt and Clive Rowland. The ascent is remembered for one of mountaineering’s greatest survival stories when Doug Scott broke both legs during the descent, yet the team managed to survive a harrowing retreat. The Ogre’s towering granite spires, steep rock walls, and complex mixed climbing routes place it among the most technically difficult 7000-meter peaks globally. Since the first ascent, only a handful of successful ascents have been recorded, cementing its status as one of the most elite challenges in high-altitude climbing.

Chogolisa — 7,665 m

Chogolisa, often called Bride Peak, lies within the Baltoro Muztagh near Concordia in the Karakoram. The Southwest Summit was first reached in 1975 by Austrians Fred Pressl and Gustav Ammerer. Its climbing history is marked by tragedy, most notably the death of renowned Austrian climber Hermann Buhl in 1957, who perished while attempting the summit after climbing Broad Peak. Chogolisa features sweeping snow domes and heavily corniced ridgelines, making it highly vulnerable to whiteouts, sudden storms, and avalanche danger. While not as vertical as Gasherbrum IV or The Ogre, its objective hazards make it a highly dangerous climb nonetheless.

Masherbrum (K1) — 7,821 m

Masherbrum, designated K1 during the 1856 Great Trigonometrical Survey, is located in the Masherbrum Mountains of Gilgit-Baltistan. The first ascent was completed on July 6, 1960, by a joint American-Pakistani team including George Irving Bell, Willi Unsoeld, and Captain Jawed Akhtar Khan. Masherbrum’s southwest face rises nearly 3,000 vertical meters, presenting a highly technical mix of steep rock, unstable snowfields, and severe avalanche exposure. Despite its prominence, Masherbrum remains far less frequently climbed than other Karakoram peaks due to its extreme technical and objective challenges.

Gasherbrum IV — 7,925 m

Gasherbrum IV sits in the Baltoro Muztagh and is widely regarded as one of the most technically challenging peaks on Earth. The first ascent was made on August 6, 1958, by Italians Walter Bonatti and Carlo Mauri, members of Riccardo Cassin’s expedition. Its infamous west face, known as the Shining Wall, presents an almost sheer vertical granite and ice face that has repelled most attempts since. Many elite alpinists consider Gasherbrum IV to be harder than several of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks, with only a handful of successful ascents since the 1958 expedition.

Distaghil Sar — 7,885 m

Distaghil Sar, located in the Hispar Muztagh subrange, is Pakistan’s highest 7,000-meter peak. The first ascent was achieved on June 9, 1960, by an Austrian team led by Günther Stärker and Diether Marchart. The peak features a massive summit plateau stretching over several kilometers, demanding long glacier approaches at high altitude. Severe weather, high winds, and complex ridge crossings make Distaghil Sar a formidable objective despite its less technical appearance compared to its steeper neighbors.

Kunyang Chhish — 7,852 m

Kunyang Chhish is one of the most technically challenging 7,000-meter peaks in Pakistan, located in the Hispar Muztagh. The first ascent was made in 1971 by a Polish expedition led by Andrzej Zawada, Janusz Kurczab, Andrzej Heinrich, and their team. Its steep ridgelines, unstable seracs, avalanche-prone slopes, and long exposed traverses make it an exceptionally dangerous climb. The mountain sits among some of the most heavily glaciated terrain in the Karakoram, surrounded by the Kunyang, Hispar, and Yazghil Glaciers.

Batura I — 7,795 m

Batura I anchors the Batura Muztagh, forming the western edge of the Karakoram Range. The first successful ascent was made on June 30, 1976, by an Austrian expedition led by Herbert Oberhofer, H. Bleicher, Helmut Rainer, and others. Batura I stands over one of the world’s longest glaciers, the 57-kilometer Batura Glacier. While technically less severe than other Karakoram giants, its remoteness, complex glacier crossings, and sustained exposure to severe cold and wind make it a serious mountaineering objective.

Kanjut Sar — 7,790 m

Kanjut Sar, located in the Hispar Muztagh, was first summited in 1959 by a Japanese expedition led by Masao Okabe. The mountain features a broad double summit and extended glaciated ridgelines. Its complex approach routes, extreme remoteness, and limited route information have resulted in very few recorded ascents since the initial climb, keeping it one of Pakistan’s least explored major peaks.

Pumari Chhish — 7,492 m

Pumari Chhish sits deep within the Hispar Muztagh and remains one of the highest seldom-climbed peaks in Pakistan. The first successful ascent was made in 1979 by the Japanese Hokkaido Alpine Association led by Yukihiro Yanagisawa. Its steep faces, heavily corniced ridges, unstable icefalls, and extreme isolation have prevented many repeat attempts. Even today, Pumari Chhish is regarded as one of the last major technical prizes for elite alpinists seeking unclimbed routes in the Karakoram.

The Challenge of Climbing 7000 Meter Peaks in Pakistan

While Pakistan’s 8,000-meter giants dominate headlines, the country’s 7,000-meter peaks pose equally serious challenges. These mountains demand elite skill, careful preparation, and respect for the Karakoram’s unforgiving conditions. For many climbers, Pakistan’s 7,000-meter peaks are more technically dangerous due to unpredictable weather, severe objective hazards, and limited established routes.

Altitude Sickness & Acclimatization

At these extreme elevations, altitude sickness (AMS, HAPE, HACE) is a constant threat. Proper acclimatization, typically over 2–3 weeks with multiple rotations to higher camps, is essential to prevent life-threatening complications.

Severe Weather Risks

The Karakoram faces volatile weather even in peak season (May–August), with sudden snowstorms, fierce winds, and extreme cold. Storm systems from both monsoon and westerly jet streams create highly unstable conditions, often forcing teams to wait weeks for safe summit windows.

Technical Dangers: Avalanches, Crevasses & Icefall

Unlike heavily guided routes in Nepal, Pakistan’s 7,000-meter climbs expose teams to constant objective hazards. Avalanche-prone slopes on peaks like Diran, unstable seracs on The Ogre and Kunyang Chhish, and hidden crevasses on glaciers such as Batura and Minapin demand advanced glacier travel and technical climbing skills.

Permit Requirements

Climbs above 6,500 meters require permits issued by the Gilgit-Baltistan Council and Alpine Club of Pakistan. Applications must be submitted 4–6 months prior, with fees based on peak height. Liaison officers, emergency plans, and insurance are mandatory components of the permit process.

Climbing Season: May to August

The best climbing window runs from late May through July, with relatively stable weather and snow conditions. Risks increase in August due to potential monsoon influence, though some peaks like Muztagh Ata remain accessible slightly longer.

Base Camps & Approach Treks

Approaches often involve multi-day treks through rugged, glaciated terrain. Routes to Rakaposhi, Spantik, Ultar Sar, Passu Sar, and K6 all require different logistical planning, with base camps generally situated at 4,000–5,000 meters.

Logistics & Local Operators

Specialized Pakistani operators such as Great Karakoram Expeditions handle permits, base camp logistics, porters, high-altitude staff, and safety management — services essential for navigating the complexities of Karakoram expeditions.

Why Pakistan is a Global Destination for 7000m Climbers

Pakistan stands apart on the world’s mountaineering map — not just because of its towering 8,000-meter peaks, but because of its unique concentration of 7,000-meter giants that remain largely untouched, technically diverse, and rich in cultural and scenic significance. For climbers seeking authentic high-altitude experiences away from heavily commercialized routes, Pakistan offers some of the purest expedition opportunities anywhere on Earth.

Unmatched Concentration of the World’s Highest Peaks

Pakistan’s Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir ranges collectively host one of the densest clusters of high-altitude peaks found anywhere on the planet. While Nepal dominates global attention for its 8,000-meter giants, Pakistan quietly offers an extraordinary catalog of more than 70 recognized peaks above 7,000 meters — many of which remain barely explored by modern alpinists.

In a relatively compact region of northern Pakistan, climbers can encounter:

-

4 peaks above 8,000m

-

Over 20 internationally documented 7,000 m+ peaks

-

Dozens more unmapped or unnamed summits approaching 7,000 meters

This concentrated geography allows mountaineers to plan multiple high-altitude objectives within a single expedition season — a rare possibility in most of the world’s other mountain ranges. Peaks like Spantik, Ultar Sar, Diran, Passu Sar, Baintha Brakk (The Ogre), and Gasherbrum IV represent a level of technical variety and natural vertical architecture unmatched anywhere else.

Untouched Routes & Less Commercialized Than Nepal/Tibet

Unlike the increasingly commercialized climbing routes found in Nepal and Tibet, particularly on Everest, Cho Oyu, and Manaslu, Pakistan’s 7,000-meter peaks remain largely untouched by mass tourism. Many of these mountains:

-

See fewer than one or two expeditions per year, with some receiving no attempts for multiple seasons.

-

Have rarely repeated routes, where successful ascents remain extremely limited.

-

Offer unclimbed faces, virgin lines, and new route possibilities for elite alpinists.

For serious mountaineers, this creates an unparalleled sense of adventure and exploration, where success isn’t measured by traffic jams at high camp but by the opportunity to climb in true wilderness, often on routes that have only seen a handful of summits in history.

Many international climbers describe Pakistan’s Karakoram as offering the type of unspoiled climbing experience that the Himalayas once offered 50 years ago.

Cultural & Natural Beauty Beyond the Summits

High-altitude climbing in Pakistan is never just about the summit. The rich cultural landscapes, ancient history, and breathtaking natural beauty of northern Pakistan elevate every expedition into a deeply immersive experience.

-

Hunza Valley: The cultural heart of the Karakoram, offering vibrant local hospitality, traditional stone villages, and dramatic views of Rakaposhi, Ultar Sar, and Ladyfinger Peak.

-

Skardu & Baltistan: The launch point for most Karakoram expeditions, filled with Tibetan-influenced Balti culture, centuries-old fortresses, and vibrant local communities.

-

Hushe Valley & Hushe Baltoro Gateway: Known for its proximity to Masherbrum, K6, Chogolisa, and the Gasherbrum cluster.

-

Glacier Systems: Massive non-polar glaciers such as Baltoro, Hispar, Batura, and Biafo—some of the longest glaciers outside the polar regions—offer surreal landscapes seen nowhere else on Earth.

-

Historic Silk Road Corridor: Many approach routes overlap with ancient trade pathways that once connected Central Asia, China, and the Indian Subcontinent.

Climbers trekking toward their base camps pass through lush valleys, vibrant apricot orchards, turquoise rivers, and fortress towns that stand in stark contrast to the towering granite walls above.

The True Spirit of High-Altitude Exploration

For many modern climbers frustrated by overcrowded camps, over-commercialized routes, or permit restrictions elsewhere, Pakistan’s 7,000-meter mountains remain one of the last frontiers of true high-altitude exploration:

-

Minimal fixed ropes or ladder installations.

-

Full expedition-style climbing without Sherpa-supported summit pushes.

-

Personal self-sufficiency emphasized.

-

A blend of alpine-style ascents and expedition-style logistics depending on route choice.

Whether you’re a climber pursuing your first 7,000-meter summit on Spantik or Rakaposhi, or an elite alpinist seeking the challenge of The Ogre or Kunyang Chhish, Pakistan offers something for every level of ambition, with all the raw beauty and difficulty that made Himalayan climbing famous to begin with.

Preparing for a 7000m Expedition in Pakistan

Climbing Pakistan’s 7000-meter peaks demands not only excellent fitness but also advanced mountaineering skill, careful logistics, and strict safety discipline. These are serious expeditions where even “beginner-friendly” peaks like Spantik or Muztagh Ata require solid prior high-altitude experience.

Fitness & Skills

Climbers need high cardiovascular endurance, strong core strength, and the capacity for long summit pushes in extreme cold. Technical skills include glacier travel, crevasse rescue, fixed-line work, steep snow and ice climbing (up to 70°), avalanche assessment, and mixed climbing for peaks like Gasherbrum IV and The Ogre. Decision-making under stress and mental resilience during weeks of waiting out bad weather are equally important.

Essential Gear

Personal gear includes triple boots, down suits, -30°C sleeping bags, glacier glasses, crampons, helmets, and full snow/ice safety equipment. Group gear involves ropes, anchors, snow protection, satellite communication devices, and comprehensive medical kits. Proper gear is critical for both climbing and surviving the Karakoram’s extreme conditions.

Acclimatization Plan

A slow, staged ascent is vital. Treks to base camps (4,000–5,000m) typically take 3–5 days, followed by multiple rotations to higher camps. Summit attempts usually occur after at least two weeks of altitude exposure. For example, on Spantik, climbers make acclimatization climbs to 5,200m and 6,000m before attempting the summit window around days 17–21.

Recommended Operators

Nearly all successful 7000m climbs in Pakistan are supported by experienced Pakistani outfitters who handle permits, porters, cooks, safety staff, and weather logistics. Leading operators include Great Karakoram Expeditions, Karakoram Tours Pakistan, Nazir Sabir Expeditions, Apricot Tours, Jasmine Tours, and Summit Karakoram.

Safety Protocols

High-altitude rescue insurance is mandatory. Medical kits must include AMS, HAPE, and HACE treatments, alongside portable oxygen where possible. Satellite communications are essential for weather updates and emergencies. Climbers should undergo medical evaluations before departure, particularly for respiratory or cardiac issues.

Even with full preparation, 7000-meter expeditions in Pakistan carry serious inherent risks. Success depends on careful planning, flexibility, and disciplined decision-making in extreme environments.

Summing Up Pakistan’s 7000-Meter Giants

Pakistan’s towering 7,000-meter peaks represent one of the last true frontiers of high-altitude mountaineering. Unlike the increasingly commercialized climbs found elsewhere in the Himalayas, the Karakoram, Hindu Kush, and Pamir regions offer climbers an opportunity to experience mountains in their rawest, most authentic form, where technical skill, self-reliance, and deep respect for nature are the real prerequisites for success.

From the towering faces of Gasherbrum IV and The Ogre, to the breathtaking symmetry of Rakaposhi, the training grounds of Spantik, and the rarely climbed spires of Kunyang Chhish and Pumari Chhish, Pakistan’s 7,000-meter peaks form one of the densest and most technically varied high-altitude collections in the world. These mountains challenge not only physical strength, but a climber’s patience, judgment, and commitment to safe expedition ethics.

Beyond the climbing itself, these expeditions carry climbers deep into some of the world’s most extraordinary landscapes and communities, through the ancient cultures of Hunza, Baltistan, Nagar, and Gojal, along glacier-fed valleys, centuries-old trade routes, and amidst some of the most hospitable people one can encounter. The fusion of technical alpinism and cultural immersion is part of what makes Pakistan’s 7,000-meter expeditions so uniquely rewarding.

Yet, with this privilege comes responsibility. Pakistan’s fragile mountain ecosystems face the pressures of climate change, glacial retreat, and growing tourism. Every expedition must aim to preserve these mountains for future generations, practicing strict Leave No Trace principles, supporting local communities, and minimizing environmental impact.

For climbers who seek more than just a summit photo—for those in search of true expedition-style mountaineering, remote wilderness, and cultural richness—Pakistan remains one of the most diverse, demanding, and profoundly rewarding destinations on Earth.

Also See: Trekking in Pakistan – The Dos and Don’ts, The Whats and The Whys

FAQs Section: 7000 Meter Mountains in Pakistan

When is the best time to climb 7000 meter mountains in Pakistan?

The optimal climbing season for Pakistan’s 7000-meter peaks typically runs from late May to early August. This window offers the most stable weather, allowing climbers to avoid the heavy snowfalls of early spring and the late monsoon risks of August. July is often considered the prime summit month. However, some peaks, such as Muztagh Ata (due to its drier Pamir climate) may offer an extended window into late August. Climbers must always factor in weather instability, especially for technical peaks like Ultar Sar, The Ogre, and Gasherbrum IV.

Do you need permits to climb in Pakistan?

Yes. All climbers attempting peaks above 6500 meters in Pakistan must secure official climbing permits through the Gilgit-Baltistan Council, Pakistan Alpine Club, and the Ministry of Tourism. Permit applications should be submitted several months in advance. Most permits require:

-

Payment of climbing fees based on peak elevation

-

Hiring a licensed liaison officer

-

Submission of expedition itineraries and insurance documentation

-

Compliance with environmental regulations

Local Pakistani expedition operators typically handle permit processing as part of their full-service packages.

Which 7000m peak is easiest for beginners?

Among Pakistan’s 7,000-meter mountains, Spantik (7,027m) — also known as Golden Peak — is widely regarded as the most suitable objective for climbers making their first attempt at this altitude. Its south-east ridge provides a non-technical, moderately angled snow and ice route, requiring strong fitness and basic alpine skills, but avoiding many of the objective dangers found on other peaks. It’s often used as a training climb before attempting 8000-meter peaks.

Muztagh Ata (7,546m), located just across Pakistan’s border in Xinjiang, is also a popular “entry-level” 7,000-meter objective due to its gentle glaciated slopes and reputation as one of the world’s best high-altitude ski mountaineering peaks.

What is the most dangerous 7000m peak in Pakistan?

Several 7,000-meter peaks in Pakistan rank among the most dangerous and technically demanding in the world. Notably:

-

Baintha Brakk (The Ogre, 7,285m): Regarded as one of the most technically difficult mountains on Earth due to its extreme mixed climbing, vertical granite walls, and severe objective dangers.

-

Gasherbrum IV (7,925m): Considered even more dangerous than many 8,000-meter peaks due to its infamous Shining Wall, vertical rock faces, and minimal margin for error.

-

Kunyang Chhish (7,852m): Known for severe ice cliffs, avalanches, and minimal successful ascents.

-

Ultar Sar (7,388m): Extremely steep, avalanche-prone, and rarely climbed due to its unstable icefalls and rapid weather changes.

These peaks demand elite technical proficiency, highly experienced teams, and maximum safety precautions.

How many 7000m peaks are there in Pakistan?

Pakistan has approximately 70 recognized peaks above 7000 meters, making it one of the densest concentrations of high-altitude mountains outside the main Himalayan belt. These peaks are spread primarily across the Karakoram Range, with additional summits located in the Hindu Kush and Pamir extensions. Many remain infrequently climbed, and some are still awaiting first ascents.

This density offers unique opportunities for both professional climbers seeking technical first ascents and intermediate alpinists looking to build their high-altitude experience in a truly wild, expedition-style environment.